Drones are everywhere these days, from far-flung battlefields to family events. Where they haven’t gone, until recently, is into the confined hull spaces of ships. There, using tools that haven’t changed much in the past century, skilled professionals have been putting themselves at risk — sometimes amid toxic fumes or inadequate oxygen — to seek signs of metal fatigue, corrosion, or anything else that might endanger the safety or serviceability of a vessel.

But that’s changing rapidly. Drones have finally invaded these inner spaces, helped along by advanced technologies that depend less on the vagaries of GPS, to pursue the work of inspection with a growing degree of autonomy. And the practice is quickly gaining acceptance.

Within the International Association of Classification Societies, London-based Lloyd’s Register has led the development of regulations to permit the use of remote inspection techniques (RIT), according to Richard Beckett, global head of technology for Lloyd’s. The initiative has included updates to survey guidance and the introduction of service supplier requirements for companies using these techniques to assess the structure of ships and mobile offshore units.

Following questions from the shipping industry and the surveyor community about when it is suitable to use RIT equipment, Lloyd’s issued a standard in 2018 — considered an industry first — for assessing the capability of these systems. The goal was to help RIT vendors and service suppliers evaluate their equipment against the criteria laid out in the standard.

Following questions from the shipping industry and the surveyor community about when it is suitable to use RIT equipment, Lloyd’s issued a standard in 2018 — considered an industry first — for assessing the capability of these systems. The goal was to help RIT vendors and service suppliers evaluate their equipment against the criteria laid out in the standard.

“This has proved a very useful framework,” Beckett said. “We have been working with drone operators for many years, helping us utilize available technology to prevent unnecessary downtime, while also ensuring safe and compliant practice.”

Recently, Lloyd’s worked with the Montreal-based cargo operator CSL when one of its self-unloading bulk carriers was due for a close-up inspection as part of its intermediate survey. The ship wasn’t due to go to dry dock until 2021, but surveyors needed access to the cargo holds. The team conducted a close-up assessment using a Lloyd’s-approved drone operator, taking advantage of the drone’s ability to examine hard-to-reach areas of the vessel while still retaining the arm’s-length requirement of the intermediate survey.

“The drone was able to capture high-quality imagery to complete the visual inspection without the need to set foot off the deck,” Beckett said. “This drone-assisted survey avoided the need for expensive and time-consuming scaffolding and staging, so CSL’s self-unloader was back in operation in record time.”

In 2019, the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS), a Houston-based classification society, published “Guidance Notes on the Use of Remote Inspection Technologies,” which similarly details best practices for drone use on class surveys and non-class inspections. The guidance covers pilot-operated unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs), and robotic crawlers.

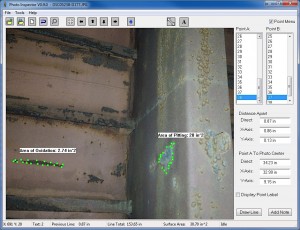

Not surprisingly, a voice from the world of drone makers is very enthusiastic about the technology’s potential for remote vessel inspections and its successes to date. Christian Smith, president of Interactive Aerial of Traverse City, Mich., said his team is currently focused on building robotic solutions to better address internal infrastructure inspections, both terrestrial and maritime. The company’s products include the Legacy One drone, Zenith robotic camera and proprietary Photo Measurement software.

Smith said Traverse City has the distinction of being the site of the first unmanned drone flight in the United States (a Navy program during World War II). It is also home to Great Lakes Maritime Academy, where three of Interactive Aerial’s co-founders took advantage of the school’s ROV-oriented engineering program, one of the few in the U.S.

Smith said drones for outdoor use have attracted most of the attention, leaving room for his company to take a leading role in “GPS-denied areas.” He said some manufacturers have simply tried to make their “inside” drones tougher and more tolerant of impacts with walls, columns and cables. Interactive Aerial took the opposite approach, equipping its drones with a spinning light detection and ranging (lidar) system so they can navigate accurately and avoid objects reliably. While the company can sell its drones to customers, typically it is hired to perform inspections since it has developed considerable experience in the field.

To date, most of Interactive Aerial’s assignments have been on land, but the company has also inspected dry bulk carriers on the Great Lakes and floating oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico.

“Typically, if drones can be used as an alternative to humans, it is safer, faster and saves money,” Smith said.

According to James Forsdyke, head of product management at Lloyd’s, one of the main advantages of using drones or other remote technology for inspections is that it can provide “high fidelity assurance.” Decision makers can be more confident that they are seeing an accurate representation of a situation, and they can access this information more easily. The use of drones also can reduce the extensive preparation and execution time often needed with traditional inspection programs, he said.

Forsdyke said there is a benefit for class societies and clients alike because the technology allows quick responses for smaller, less critical tasks, helping vessel owners and operators reduce unnecessary downtime and resume operations in a safe and timely manner. From a class perspective, a surveyor’s skill is rooted in analyzing the collected data, and that’s where their time is better spent — not undertaking an on-site inspection.

“Remote surveying techniques can facilitate a more efficient collection of data while allowing surveyors to focus their energies on the interpretation of the evidence,” he said.

Although drones can provide a number of advantages when it comes to ship inspections, they are not always the answer. For example, it is not always possible to have sufficient bandwidth to transmit livestreaming data. The complex metal structures of a hull also can constitute a Faraday cage — in other words, a very effective signal disruption. The suitability of drones must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, Forsdyke said, ensuring that there is an actual equivalence with normal survey techniques.

While many in the shipping industry had already begun to accept the use of drones for surveys and inspections before COVID-19, the pandemic has accelerated the process, according to Beckett. In addition to making use of standard forms of communication, such as email and mobile phones, “we are actively engaging in the use of remote connectivity, remote data feeds and live video streaming to support our clients at this challenging time, and to assist them with keeping their fleet and other assets in service,” he said.