U.S. regulations to reduce water pollution from equipment below the waterline will lead to operators of large commercial vessels swapping out mineral-oil lubricants for products that meet new standards.

As of Dec. 19, 2013, under the 2013 Vessel General Permit (VGP), operators of commercial vessels more than 79 feet long must use environmentally acceptable lubricants (EAL) in oil-to-sea interfaces — also known as water boundary propulsion systems — when inside the 3-nm limit and in the Great Lakes. The requirements cover approximately 70,000 existing VGP vessels, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

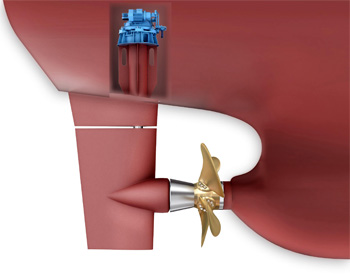

The EPA said the lubricants should be used in a wide range of equipment, including stern tubes, controllable-pitch propellers, stabilizers, rudders, thrusters, Azipods, towing notch interfaces, wire rope and any mechanical equipment subject to immersion such as dredges and grabs.

However, the original manufacturers of various equipment required to use the new lubricants must certify products before vessel operators can safely put them to use.

The VGP outlines circumstances in which it is “technically infeasible” to switch to EALs, which must be noted in a vessel’s annual EPA report. One acceptable reason for delays is the changeover to an EAL must wait until the next dry-docking. Other reasons for delay include pending certification from the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) or the lack of availability of EALs at any port at which the vessel calls. The U.S. Coast Guard has enforcement authority from the EPA to uphold the requirements of the VGP.

“The major challenge for operators is that by definition most of the systems that are impacted are below the waterline so the vessel needs to be pulled out of the water to make the change,” said Iain White, field marketing manager for ExxonMobil Marine Fuels and Lubricants.

The EPA also encourages use of the EALs in all above-deck equipment to further reduce the risk to the environment. For above-deck equipment, such as wire ropes, the EALs should be adopted because OEM recommendations or dry-docking are not required, said Ben Bryant, marine market manager at Klüber Lubrication.

According to the 2013 VGP, the term “environmentally acceptable lubricants” means lubricants that are “biodegradable” and “minimally-toxic” and are not “bioaccumulative,” which have performance standards defined by the EPA.

The EPA notes that the majority of oceangoing ships operate with oil-lubricated stern tubes and use lubricating oils in on-deck and underwater machinery. Oil leakage from stern tubes, once considered a part of normal “operational consumption” of oil, results in millions of liters of oil released into the water every year. A typical stern tube system holds 400 gallons to 800 gallons of oil and the average vessel leaks about 1.6 gallons or 6 liters of oil per day.

In mandating EALs, the EPA designated four types of formulations for environmentally acceptable lubricants: vegetable oil, biodegradable synthetic ester, biodegradable polyalkylene glycols, and water. Thordon Bearings has developed seawater-lubricated stern tube systems that use non-metallic bearings instead of metal bearings that require mineral-based lubricants or EALs. They have been deployed on more than 500 vessels.

For purposes of the VGP, products that meet the definition of being an “environmentally acceptable lubricant” include those labeled by Blue Angel, European Ecolabel, Nordic Swan, the Swedish Standards SS 155434 and 155470, Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), and EPA’s Design for the Environment.

OEMs such as Rolls-Royce will provide vessel operators a letter regarding the status of certification for a particular equipment model.

Some operators switched to white oils within the past few years as the best environmentally friendly alternative at the time, but those lubricants will no longer be acceptable.

“A lot of operators think they went in an environmentally friendly direction three or four years ago, and now they have to change again,” said Jim Kovanda, executive vice president with American Chemical Technologies, a lubricant distributor and manufacturer of polyalkylene glycol lubricants.

Operators should check with original equipment manufacturers for recommended EALs and any changes in service intervals or procedures.

“Now the onus is on the lubricant manufacturers to gain all the OEM approvals that are necessary, including confirmation of seal compatibility,” Kovanda said.

In many cases it’s the seals used in the machines that are typically the most sensitive parts, White said.

“Manufacturers may find some of the seal materials they use are not compatible with some oils, so the manufacturers have to check (that) as part of their lubricant approval process,” White said. “So operators need to be aware before they make a change-out that the new lubricant is approved for use.”

It will be vital for operators to understand what type of seal material is in the equipment and whether it would need to be upgraded.

“If a seal system is an older one, you wouldn’t want to put an EAL product in there until you can get to dry dock and put the newer seal system in there,” Bryant said. “One of the most time-consuming parts of this transition to EALs is making sure everything is compatible.”

Some operators have adopted the new EALs early, Kovanda noted. For instance, his company was involved in the conversion of a controllable-pitch propeller system on a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredge, and the bow thruster on a U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker.

In each case, the company had to confirm seal compatibility before the full changeover.

White recommends that a full drain of the system be performed to remove as much of the previous product as possible to avoid mixing with mineral-based lubricants.

“There are some types of oils that people need to be careful of depending on the nature of the oil,” he said. “We recommend minimal mixing to ensure you experience the full benefit of the performance of the new product and it maintains the environmental integrity of the product as well.”

However, some systems may present more of a challenge.

“With a grease system you may need to put the new grease on the top of the old one. It may be possible to pump some through, but with a rudder system it isn’t always possible,” he said. “The lubricant will work its way through in time.”

Wärtsilä, for example, produced a stern tube seal ring designed for use with EALs. The company said it expects the seal to last five years, double the life span of conventional seal rings.

While OEM certifications are underway in many cases, the lubricant manufacturers don’t expect any negative tradeoffs for the new EALs. In fact, the opposite may be true.

“Typically one should see improved performance in the machine itself and the overall oil life could potentially be increased,” White said. “There should be no downside to it, but performance varies by machine depending on how arduous the situation is.”

The EPA estimates that the cost for EALs will be 50 percent to 120 percent more than mineral oils, for an average annual increase of $555 to $1,111 per vessel.

While the EALs may cost more, it’s likely they will offer a service life three to four times as long as mineral oils, Bryant noted.

“We recommend you sample the oil regularly so you know the product is still performing as it should,” Bryant said. “If there are situations where the bearings or the seals are getting overheated, the synthetic ester oils will be able to withstand that longer than a mineral oil.”

Operators of multiple vessels, such as liner carriers and cruise liners, have a dry dock schedule and can rotate their fleet through the scheduled service to change over to EALs. That gives them time to receive new service information from manufacturers.

“The EPA is not forcing vessels to come in for dry dock, so there’s time for OEMs and lubricant makers to wrestle back and forth on compatibility, and in the meantime vessel operators can wait until the OEM says it’s OK to go ahead,” Kovanda said. “It’s going at a slow pace, but that’s not unexpected. Operators know they have to make a change, but they’re not all necessarily doing it yesterday.”