Salvage contractors successfully completed the recovery of oil from a U.S. Army transport vessel that sank on British Columbia’s North Coast on Sept. 26, 1946.

The Canadian government’s two-month, C$50 million operation safely extracted approximately 11,623 gallons of heavy bunker C oil and 84,391 gallons of oily water from the wreck. Customary “hot tapping” methods could not be used because of the poor condition of the vessel’s tanks.

The primary contractor was Mammoet Salvage Americas. Subcontractor Global Diving & Salvage Inc. provided the hands-on diving and underwater recovery. The salvors were faced with challenges including the precarious position of the ship along a ledge, unexploded ordnance on board and deteriorating metal.

Many adjustments were made on the fly, said David DeVilbiss, vice president of marine casualty and emergency response services at Global Diving.

“The internal parts of the tanks were very corroded,” DeVilbiss said. “We had to change our work plan because our plan relied on the integrity of the tanks to circulate hot water to heat it all up. It was a surprise and we adapted to it.”

|

|

Canadian Coast Guard/Dan Bate |

|

Salvage barge Seaspan 202 is on station with tugboat Smit Norman in British Columbia’s Grenville Channel as part of an operation to recover oil from a U.S. Army transport ship that sank in a storm in 1946. The diver launch-and-recovery system is amidships. |

The 251-foot Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski was en route from Seattle to Whittier, Alaska, with military supplies when it struck rocks at Pitt Island in bad weather and sank within 20 minutes in Grenville Channel, 55 miles south of Prince Rupert. The crew of 48 was rescued by the tug Sally N and passenger ship SS Catala.

Zalinski was carrying a cargo of at least 12 500-pound bombs, large quantities of .30- and .50-caliber ammunition, and truck axles with tires. It was laden with 700 tons of bunker oil.

It was the leak of oil from the wreck that prompted the recovery effort.

In September 2003, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Maple reported pollution in Grenville Channel to the Canadian Coast Guard. The Canadian Coast Guard vessel Tanu went to investigate the source of the pollution and collected oil samples, but Zalinski remained undetected.

A pilot reported oil pollution in the area in October 2003. Again, on investigation, no source could be found, but the Canadian Coast Guard suspected that the oil could be surfacing from an old wreck.

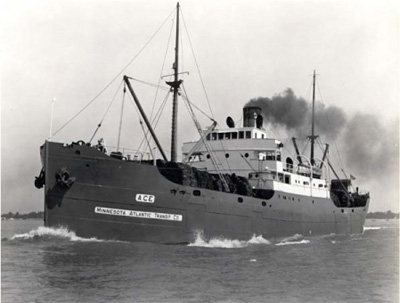

Zalinski was built as Lake Frohna at the American Ship Building Co. in Lorain, Ohio. It was a cargo vessel for the United States Shipping Board and was delivered in June 1919. In 1924, it was sold to the Ace Steamship Co. and renamed Ace. In 1930, Ace was sold to the Minnesota Atlantic Transit Co. of Duluth, Minn. Finally, in 1941, it became Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski in the employ of the U.S. War Department.

On Oct. 30, 2003, the wreck was located with oil escaping from cracks in the hull. The Canadian Coast Guard contracted divers to patch the vessel to prevent further leakage. In January 2004, mariners were informed to avoid anchoring or fishing near the sunken vessel.

The wreck sits upside down on a rocky shelf in 130 feet of water. Since the wreck was discovered, the Canadian Coast Guard launched several operations to patch and seal Zalinski as new upwelling became evident.

The Coast Guard regularly monitored the site with the help of Transport Canada’s National Aerial Surveillance Program, and kept in frequent contact with local First Nations groups.

No further upwelling of oil was reported until April 2012, and the Canadian Coast Guard contracted divers to patch the vessel with a commercial epoxy compound that cures and hardens underwater.

|

|

Canadian Coast Guard/Dan Bate |

|

A diver from Global Diving & Salvage prepares to exit the barge’s launch-and-recovery system after finishing a shift on the wreck of Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski. |

In January and March of 2013, further upwelling was reported and the Canadian Coast Guard took action to again patch the vessel. Although the patches from 2012 and 2013 remain in place, early patches were leaking and the Canadian Coast Guard determined that the structural integrity of the vessel was deteriorating. Dive footage indicated that metal rivets which hold the hull’s plates were corroding and that the hull was buckling.

Not knowing the internal condition of the vessel was one of the problems the salvage crew had to deal with when they started the recovery operation.

“Nobody knew the condition of the internal tanks,” DeVilbiss said. “As we worked we had to adapt to what we learned there. We had to be light on our feet and make changes to our work plan. … We started with an assessment of the stability of the vessel. One of the concerns was that it was perched on a ledge.”

“We went to work checking the tanks, drilling holes to find out where the oil was,” he explained. “By the time we established connections to suck the oil because of the corroded nature of the tanks, we knew we had to send divers in to some areas to suck oil out of the overhead inside.”

After placing infrastructure during the summer and autumn of 2013, the actual oil recovery operation commenced Nov. 19 and was completed Dec. 2.

Initially salvors intended to use a process called “hot tapping” to remove oil from the vessel. In the hot-tapping procedure, holes are carefully drilled into the side of the vessel to access fuel tanks, and then hot steam is pumped into the tanks. The steam increases the temperature of the oil and enables it to flow more easily. The oil is then pumped to the surface for safe disposal.

The poor condition of the internal spaces of the wreck meant that the hot-water recirculation method could not be used as the tank tops were rusted away, according to Canadian Coast Guard spokesman Dan Bate.

“The oil had migrated to various high places in the wreck,” Bate said. “Instead, pumps and hoses were connected to each of the hot tap locations and the bunker was sucked out of the hull. This resulted in the added recovery of (84,391 U.S. gallons) of oily water which was drawn up with the oil. Both oil and oily water were recovered and pumped into large tanks on the surface.”

In addition to the remoteness of the location, DeVilbiss said that preventing changes in the ships buoyancy and the unexploded ordnance aboard were two more challenges.

“Normally the divers exhale their breath into the water column and the bubbles just go out of their hat,” he said. “We had some special equipment we designed so that when the diver exhaled, his exhaled gas would come up to the surface through a second hose. That way we didn’t add a whole bunch of buoyancy into the boat that we didn’t want.”

With bombs and ammunition in the cargo, DeVilbiss said the divers did not use the usual cutting and burning techniques with welding equipment to make holes in the ship.

“Because of the ordnance we used all mechanical cutting methods,” he said. “There were electric detonators as part of the cargo. It was definitely an unusual one that we don’t always have to take into account.”

Another unique feature of the job was that Zalinski was an old riveted ship. If the rivets corrode away, the plates detach, said Bas Coppes, president and director at Mammoet Salvage Americas. In addition to being fragile, the ship capsized on a very steep slope.

“She was upside down hanging on a ledge, Coppes said. “She was only 17 meters (55 feet) underwater but if she slid off, she would go to 120 meters (390 feet) into the abyss. It was a delicate situation, because the moment you remove oil you change buoyancy. The risk is that by changing the buoyancy the vessel could tip off the ledge and go 120 meters down.”

As DeVilbiss explained, the cargo of unexploded bombs aboard Zalinski, along with rifle and machine-gun ammunition, was a concern. The tides and weather were a factor a well, Coppes said.

“The very high tidal currents made the diving very challenging and time-consuming,” Coppes said. “We did it in the worst season, the winter. We had snow and freezing temperatures and all that kind of stuff — pretty tough conditions.”

The cold water directly affected the oil recovery.

“The seawater is very cold and the viscosity of the fuel is very low, so it was very difficult to pump,” he said. “Also the internals of the ship turned out to be completely corroded away and we had to go into the ship to pump. There was a lot of hard work to find the oil patches within the ship.”

Coppes said the team is “proud that we have removed this environmental threat from the pristine British Columbian coast.”