Until two years ago, the southerly movement of crude oil by barge between the Midwest and the Gulf Coast was almost nonexistent.

As a result of a boom in domestic oil production — particularly in the Bakken Shale formation that stretches from western North Dakota into Montana and Canada — tug and barge companies have jumped into the “black gold” rush and experienced unprecedented growth.

Kirby Corp., the industry’s largest company, was the first to receive public attention for loading crude onto barges in 2012 and transporting it south to refineries in the lower Mississippi and the Gulf Coast. Kirby said 7 percent of its inland business is crude, as of the second quarter of 2014. Other companies have stepped forward to claim a piece of the business.

“For many, many decades, crude oil movement in this country has been south to north,” said Darrell Conner, a government affairs counselor and transportation and trade expert for K&L Gates, an international law firm. “Now it is reversed. It’s moving north to south. The same thing has happened in the tug industry.”

Matt Woodruff, Kirby’s director of government affairs and general counsel to the Inland Waterways Users Board, agreed.

“Oil is moving in a different direction; so is gas. What we’re seeing as a result of the shale plays is a renaissance of sorts,” he said. “Supply is coming from nontraditional sources and putting stresses on all modes of transportation to get the product to market.”

Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows that stress, and the reason the tug and barge industry experienced such growth: In 2008, about 3.9 million barrels of crude were moved by barge from the Midwest to the Gulf Coast; in 2013, that number jumped to 46.7 million barrels.

RBN Energy LLC, an energy analytics and consulting firm, said crude-by-barge traffic has grown eightfold in the past three years and black-oil barges — those used for crude — are between 90 and 95 percent utilized, a fact Kirby said is true of its own fleet.

Construction of new tank barges and vessels is booming, too.

In 2013, the peak of the crude-by-barge movement, vessel operators on the inland waterway system took delivery of 336 tank barges with an aggregate capacity of approximately 8.21 million barrels — far exceeding the record of 261 new tank barges delivered in 2012, American Waterways Operators (AWO) said.

Kirby, the industry giant, has made a substantial investment in the oil boom. Its inland barge fleet represents approximately 25 percent of U.S. inland tank-barge capacity, transporting petrochemicals, black oil, refined products and agricultural products, according to its website. Its fleet includes 874 tank barges with 17.3 million barrels of capacity, and 252 towboats. The company is adding 66 tank barges in 2014, some of which will be offset by the retirement of old barges.

“Two years ago, nobody expected this boom. It took everybody by surprise,” said Rob Grune, senior vice president and general manager of Crowley Maritime Corp., which is expanding its considerable chunk of the market on coastal waterways. “Since that time, pipelines have been reversed, vessels are being built, railroad tank cars are being built. It’s really come upon us quickly.

“It’s been a very good thing for the country as a whole, leading us closer to energy independence.”

For decades, the United States has depended on foreign oil to keep it running.

Refineries along both coasts and the Gulf of Mexico were geared to offload crude from giant tankers, process it and move it inland. In a historic snap of the fingers, that all changed.

Energy companies had known about hydraulic fracturing — or fracking — for years. But in 2004, a landmark study conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency found that hydraulic fracturing posed no threat to underground drinking water supplies — a conclusion disputed by activists. Shortly thereafter, the process was exempted from the Safe Drinking Water Act by the Bush administration in the Energy Policy Act of 2005.

Fracking — the process of pumping a cocktail of water, sand and chemicals under high pressure into a well to fracture the shale and stimulate production — allowed energy companies to reach and extract oil reserves trapped in shale formations thousands of feet underground.

Almost overnight, oil-rich formations, such as the massive Bakken Shale, which encompasses 220,000 square miles, turned into a real-life episode of “The Beverly Hillbillies.” The rush was on to drill for oil and move it to the nation’s refineries.

But how were the companies going to deliver the crude? The nation’s pipeline infrastructure just wasn’t — and isn’t today — sufficient to handle the staggering volume of crude coming from these new-found honey pots, particularly the Bakken. In November 2006, there were 284 active wells in the Bakken, producing 10,572 barrels of oil per day. By July 2014, the last available data, 8,065 active wells were producing 1,047,044 barrels per day.

Pipeline capacity became exhausted, and many pipelines were flowing in the wrong direction — south to north to accommodate the movement of foreign oil. Energy companies turned to rail and barge to handle the overflow.

Rail provided flexibility. Unit trains with 120 tanker cars carrying roughly 85,000 barrels of oil could move in any direction, based on market conditions. Some headed south to Cushing, Okla., a major crude trading, storage and shipping hub where dozens of pipelines intersect. Others headed directly to refineries on the East, West and Gulf coasts.

Others headed to ports where the crude could be offloaded onto barges and moved more economically and efficiently into any refinery that has waterborne access.

One river barge can hold 10,000 to 30,000 barrels of oil. Two or three barges tied together in a single tow carry as much as 90,000 barrels in one shipment. That’s more oil than an entire unit train can carry. Industry estimates say it takes about 47 train cars to fill one 30,000-barrel barge.

Articulated tug-barges (ATBs), designed for the open seas, became major players. Newer ATBs can hold as much as 340,000 barrels, comparable to coastal tankers. With the median capacity of U.S. refineries at about 160,000 barrels a day, a newer ATB or a coastal tanker can deliver a two-day supply of oil.

|

|

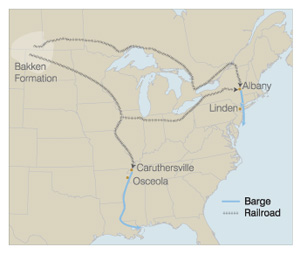

Bakken crude travels first by rail to the Mississippi and Hudson rivers. Barges carry it south to refineries in Louisiana and New Jersey and coastwise. Among the transfer points is Caruthersville, Mo., and a new domestic-oil port is being developed at or near Osceola, Ark. For Hudson River transit, crude is loaded onto barges at Albany, N.Y. |

|

Virginia Howe illustration |

Today, inland and coastal barges transport millions of barrels of crude from oil plays across the country.

Kirby said despite its vast size, it has not been a major player in transporting crude on inland waterways, according to Sterling Adlakha, director of investor relations at Kirby and the company spokesman. “It’s been very important for the industry. Probably more substantial to the rest of the industry than us,” he said.

The strong demand for transporting crude on barges has even helped towing operators who aren’t involved. Austin Golding, marketing manager and co-owner of Golding Barge, said his Vicksburg, Miss., company hadn’t “chased the crude bubble,” but he did acknowledge that trend aided a broader plan.

“Our strategy was to do what we know best, and to provide the great service to our customers that we’ve always provided,” he said.

Golding said his business benefited when competitors jumped into the crude market, leaving a bigger chunk of existing business for Golding. As a result, Golding grew its fleet from eight boats in 2009 to 20 as of 2015, and increased its workforce from 120 in 2009 to between 220 and 230 today. “The vast majority of them are onboard personnel,” he said.

The AWO said most of the crude being moved from the Midwest to the Gulf Coast by barge is coming from Canada by pipeline and loading onto barges in Illinois. Other ports are receiving trains of crude from Canada and the Bakken.

Some of that crude is moving south by train to ports including the Pemiscot County Port Authority in Caruthersville, Mo., about 185 miles south of St. Louis. A great deal of it — two mile-long unit trains with 80 to 120 cars per day — is heading east to oil terminal operators in Albany, N.Y., along the Hudson River.

Sandor Toth, who runs the online newsletter Rivertransportnews.com, said that has been the biggest change. “We went from less than 2 million barrels to about 15 million barrels per month going to the East Coast by rail,” he said.

According to Rich Hendrick, the Port of Albany’s general manager, the growth in crude traffic at his port began in mid-2012. Now, one of two berths at the port is being used daily for loading crude onto barges.

Global Partners, which operates adjacent to and in cooperation with the port, is under contract to transport 91 million barrels of Bakken crude by barge over five years to a Phillips 66 refinery in Bayway, N.J., near Linden.

Hendrick said Reinauer Transportation has the majority of the tug business at his port, transporting Global products by ATBs — likely 100,000-plus barrels per shipment, he said.

Adlakha, the Kirby spokesman, said his company is also doing work on the Hudson, though he declined to reveal specifics.

The other Port of Albany terminal operator, Buckeye Partners of Houston, has a 32-acre tank farm there. Once every eight days, the tanker Afrodite makes a call to the port and is loaded with crude for a trip north to the Irving Oil refinery in Saint John, New Brunswick, Hendrick said. There’s talk, Hendrick said, of Buckeye adding a second ship.

It’s all added up to big business in Albany, and a catalyst to help resuscitate dying refineries from New York to Philadelphia.

Trisha Curtis, an analyst for the Energy Policy Research Foundation, said Albany has become such a major player that it’s getting 20 to 25 percent of Bakken’s rail exports.

So what does the future hold? Conner, of K&L Gates, said the tug and barge industry has responded extremely well to meet market demands.

“It’s an extraordinary time to be in the shipping business today,” he said. “To quote Rich Kinder from Kinder Morgan, ‘The shale oil revolution has changed transportation for all sectors.’ Everyone is adjusting to meet the new demand.”

But Conner said as production increases, the infrastructure will have to grow with it and the investment in pipelines will increase.

“Pipeline will clearly compete with the tug and barge industry,” he said. “My guess is pipeline will compete very vigorously against all other modes of transportation. They tend to be the most efficient way to move oil. It’s just a matter of getting the regulatory process to work and to get it done (pipelines built) in a timely manner.”

That reality is likely the reason Kirby hasn’t jumped feet first into the inland crude-by-barge movement.

“We have been methodical and very thoughtful about how we’ve added crude into service,” Adlakha said. “The most economical (mode) is pipeline.”

Toth said the crude-by-barge phenomenon reached its peak in the third and fourth quarters of 2013.

“Crude volume took a pretty significant dip this year,” he said. “More and more crude is moving by rail to East Coast refineries, siphoning off crude that could move by barge.”

As more pipeline comes online, the demand for crude-by-barge will wane further, he said. The Flanagan South Pipeline, an Enbridge Energy Co. project, is expected to be operational by the end of 2014. The nearly 600-mile, 36-inch-diameter pipeline will allow oil to flow from Pontiac, Ill., to the hub in Cushing, crossing under the Mississippi River — and past barge operators — as it enters Missouri.

“Barge is at the tail end of that (crude) market,” Toth said. “It’s past its peak.”

Conner agrees the development of infrastructure will have more of an impact on the tug and barge industry than the availability of the product.

“Will it tap out or grow? That’s the $64,000 question,” he said. “For the foreseeable future, we will see production continue to grow. In 2013, we produced 7 million barrels a day; by 2020, we’ll be north of 12 million per day.

“At some point, the industry will get to the point where it’s somewhat saturated. It’s like anything else, if you’re making widgets or whatever. When something occurs so rapidly, the infrastructure always lags.

“Every mode of transportation is responding extraordinarily well. At some point, we will have sufficient infrastructure to handle this and achieve energy independence in this country.”