After decades of neglect and slow progress, mariners have grown more accustomed to donning survival gear — life jackets and immersion suits — or at least keeping the protection close at hand. The cudgel of regulation has made everyone pay attention, and more rule changes are being weighed.

According to Natasha Brown, media and communications officer for the International Maritime Organization (IMO), updates to life jacket requirements are now being proposed by the IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), which met most recently in June.

The first matter on which the committee focused, according to Brown, was the in-water performance of SOLAS-approved life jackets. The panel considered a number of relevant documents and proposed two further sessions to complete updates, assigning the IMO’s Subcommittee on Ship Systems and Equipment as the coordinating group. Among other instructions, the MSC asked the subcommittee not to create the impression that existing life jackets are not safe, nor to apply any safety requirements retroactively. It is possible that whatever new language is developed may be applied only to equipping new ships.

|

|

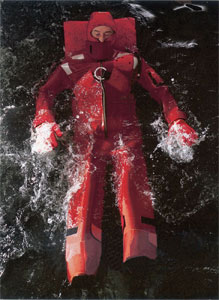

The process of improving and streamlining regulations for survival gear differs between countries, and there are differences between American and European methods. Here, a Stearns 1590 immersion suit undergoes product testing. |

|

Courtesy Stearns |

The other major issue getting attention from the MSC was the harmonization of life jacket requirements between the 1994 and 2000 HSC Codes and SOLAS Chapter III. The stated goal of the committee is to adopt new language for safety gear by July 1, 2022, with an effective implementation date at the start of 2024.

Another potentially important regulatory change is also in the works in North America. According to Wayne Walters, vice president of research and development at Kent Sporting Goods Co., a standards technical panel (STP) at Underwriters Laboratories is working on developing ANSI/CAN/UL 15027, which will create a joint U.S. and Canadian standard for immersion suits and abandonment suits.

Walters is looking to the STP to take an important step forward to harmonize the two nations’ standards while considering global standards as well. The work “will cover all the different kinds of suits and will be based on different approval categories,” he said.

The STP includes parties from both countries, said Rob Rippy, product safety and regulatory affairs manager at Newell Brands, which markets survival gear from Stearns. According to Rippy, there haven’t been any big changes in standards affecting his company’s equipment for some time, although Transport Canada added language about buddy lines and lifting straps for both life jackets and emergency suits around 2010.

The work of the current STP “has gone out for review and the comments have been addressed, but I think there are probably still some outstanding issues,” Rippy said. He said there has been a particular emphasis on the testing side, since Canada has been focusing on that area.

According to the Standards Council of Canada, the relevant ISO 15027 code specifies performance and safety requirements for “constant-wear immersion suits” for both work and leisure activities, and is intended to protect the body of a user against the effects of cold-water immersion, such as cold shock and hypothermia. ISO 15027 is applicable for dry and wet constant-wear immersion suits. However, this specific standard does not cover abandonment suits. Those are described in ISO 15027-2:2012, and test methods for immersion suits are provided in ISO 15027-3:2012.

The process of improving and streamlining regulations for survival gear differs between countries and continents. Marty Jackson, who has been involved with other harmonization efforts as a staff engineer at the U.S. Coast Guard’s Office of Design and Engineering Standards, said there is a key difference between U.S. and European testing.

“One thing we do different in the U.S. versus Europe is we require human subject testing,” Jackson said. Europeans use thermal mannequins for many tests, though they still use people for “jumps” and some other performance measurements. “We require humans for thermal testing because there is not yet any standard for thermal mannequins” to validate the trials, he said.

|

|

Viking YouSafe immersion suits comply with the latest SOLAS and U.S. Coast Guard regulations. The company’s Polar line has been tested to perform under Arctic conditions, most recently during the SARex expeditions in Svalbard. |

|

Courtesy Viking Life-Saving Equipment |

Jackson explained that a recent Coast Guard review of maritime casualties showed the importance of testing survival gear. But he added that with current or future equipment, being able to use it successfully when needed involves practice and training, not just a check-the-box exercise.

Rippy stressed that ongoing testing in the field is of critical importance regardless of what kind of gear manufacturers provide. Shipboard inspections are also important “to make sure the equipment is compliant and to make sure (there aren’t issues) that would affect flotation and thermal protection,” he said.

Although mariners in the past were notoriously reluctant to encumber themselves with safety equipment, Walters said that has changed. But the key issue that still determines whether the gear is used is sizing. While much safety gear on the market is, nominally at least, “one size fits all,” vessel operators and mariners want more options. Walters said Kent offers universal sizes as well as small, intermediate and “over” sizes, so purchases can be based on actual crews.

“The primary thing to remember is to make sure you get the suits that fit your needs, and that they are sized appropriately for your crew,” Walters said. Rippy at Newell Brands agreed. “There are some big guys and gals out there,” he said. “I have heard of people having to struggle with their equipment, so the main thing is to try them on first and make sure they fit.”

|

|

The International Maritime Organization’s Maritime Safety Committee, which met most recently in June, has proposed updating its life jacket requirements. Prominent suppliers worldwide include Stearns, with three of its products shown in use here on a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredge. |

|

Courtesy Stearns |

Jackson said that while a device may be “universal fit,” mariners must check for themselves. “(Suits) get tested to a standard, but not so much for extremes, whether it is weight, height or whatever,” he said. Trying on equipment will reveal whether, for example, it is too big for a given individual, possibly covering their mouth or even popping up over their head in use.

“There’s probably a lifespan that a suit should be good for just sitting on the shelf, but it is important to do the required inspection tests and make sure joints are watertight, and that people can put them on and that they fit,” Jackson said.

Training is also indispensable, he said. Although often not required, trying on survival gear and testing the ability to don it quickly can be life-saving in an emergency. “You can’t figure out how to use it in five minutes, especially in the cold,” Jackson said.

The other critical “field” issue, according to Walters, is professional maintenance and regular inspections. “Make sure you have a service you can trust that can check watertightness, fix holes, lubricate zippers and reattach missing reflective devices,” he said.