It’s an autumn morning on the Ohio River, and towboat crews stand ready to drop off empty barges and pick up loaded ones.

Aboard the 1,550-hp Chuck Piepmeier, Capt. Roger Dittelberger is upbound piloting near downtown Cincinnati. A question rings out from another boat.

“Where these barges at? They down yonder?” says the voice on the radio from Judith Ellen. “Just give us a shout when you’re ready to start putting them together.”

It wasn’t long before Chuck Piepmeier itself was en route to pick up a barge. Both vessels are part of the McGinnis Inc. fleet of 10 boats based at the newly designated Ports of Cincinnati & Northern Kentucky. Here, year-round, the inland trade moves cargoes ranging from petroleum and edible oils to coal and cement.

|

|

Capt. Roger Dittelberger steers the boat up the Ohio River. |

Previously, the Port of Cincinnati officially encompassed a 26-mile-long stretch of the Ohio River that ranked 51st on the list of the largest U.S. ports. Beginning in 2015, the Army Corps of Engineers recognized a consolidation into the newly named regional port that covers 227 river miles. The expanded port now ranks 15th and is the nation’s second-largest inland port by cargo volume.

Chuck Piepmeier is named for McGinnis’ longtime dispatcher who is in his 28th year with the company and is now systems information manager. The vessel’s crew joked that the Ohio Valley sometimes has a reputation as being a “retirement river” or an “old man’s river.” Tows are smaller — a maximum of 15 barges because of lock size limitations — than in the Mississippi River system, which has swifter currents and is deeper.

The Ohio River does pose plenty of navigation challenges, however. For example, there are bends and bridges where the pilot must literally slide the tow slightly sideways during the transit.

|

|

Chuck Piepmeier deck hand Josh Kuntz prepares to tie up. Kuntz also serves as an oiler and came up through the McGinnis steersman training program. |

“This is an area called Old Southern Harbor and this is a hard turn,” Dittelberger said as Chuck Piepmeier approached downtown Cincinnati at mile 473. Captains need to think ahead and be alert on this stretch of river, and “they shoot around the bend and they slide a little sideways.”

Dittelberger’s deck hand on this day, Josh Kuntz, also serves as an oiler and steersman aboard McGinnis boats. Like most of the McGinnis pilots, Kuntz rose through the ranks in the company’s internal steersman training program. He said the bridge transits are a challenge.

Two rail bridges and three highway bridges connect Cincinnati with Covington, Ky. A vessel motoring upriver first encounters the Cincinnati Southern Bridge, a rail crossing. Then, in rapid succession, the pilot is greeted by Brent Spence Bridge, C&O Railroad Bridge, Clay Wade Bailey Bridge and finally John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge. Three more bridges await at Newport, Ky.

“The bridge piers are not aligned,” Kuntz said. “You’re going through one bridge and you’re already lining up for the next bridge. Your knees knock when there’s a lot of current and speed because you don’t want to miss.”

|

|

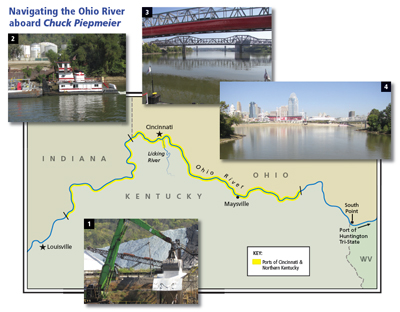

Photos: 1. Salt is unloaded from a barge at a Kinder Morgan facility on the Ohio River. 2. Susan E with a tank barge at Westway Terminal at Cincinnati. 3. Transiting rail and highway bridges between Ohio and Kentucky. 4. Exiting Kentucky's Licking River toward downtown Cincinnati. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/Photos by Dom Yanchunas |

Navigating under those bridges is even more complicated in the spring with the seasonal currents and ice floes, said Doug Hedrick, the company’s manager of marine operations.

“The bridges in Cincinnati are one of the toughest set of bridges on the river,” Hedrick said. “There are high-water restrictions. High water is a game-changer around here. It restricts the size of tows and it can be daytime-only for the bridge transits.”

The 66-foot-long Chuck Piepmeier is powered by a pair of Caterpillar C32 V8 main diesel engines. The 24-foot-wide vessel was built in 1975 at Pascagoula, Miss., and until recently was known as Avon II until it was renamed for Piepmeier. The boat is steel-hulled but the wheelhouse is aluminum. In the house, Dittelberger and Kuntz navigate with the assistance of Furuno radar and AIS and Garmin GPS units, and can view a pair of Caterpillar engine displays.

|

|

Kuntz checks one of Chuck Piepmeier’s two Caterpillar C32 engines. |

Recreational traffic also can be a challenge on the river, especially when the operators are intoxicated or aren’t focused on safe navigation practices around the commercial channel — or both.

“The motorboats are horrible, between the drinking and not paying attention,” Dittelberger said. “They’re out for their leisurely Sunday drive, and they don’t know the Rules of the Road.”

In the harshest weather, inside the wheelhouse Dittelberger always wants to do his best not to exacerbate the conditions for crewmembers working outside in the fleets.

“Positioning barges within all the elements can be tough when they’re against you,” Dittelberger said. “When your deck hand is really fighting the elements and fighting the snow, and you’re having a hard time seeing the barge, that’s pretty tough.”

|

|

Another McGinnis boat, Susan E, motors to its next job. |

Cold winter weather is to be expected in the Ohio Valley, but the towboat crews have come to expect the unexpected too. Once, a floating restaurant full of people broke loose from the Kentucky side of the river while ice from the nearby Licking River was pouring into the Ohio. Dittelberger was piloting a towing vessel that stood by, ready to respond if needed.

“It was an old barge that had a restaurant on it. The ice floes broke all the lines and wires. It landed against a bridge pier. It wasn’t going anywhere at the time so we just floated around it and made sure that no one was jumping off it,” he said. Other vessels were hired to rescue the stranded vessel and no one was hurt.

Hedrick, who was a full-time river pilot for eight years, recalled a rescue incident from several years ago involving eight people who certainly did not expect a water tour that day.

“A hot-air balloon landed in the river and floated up against a bridge. The basket was half-submerged,” Hedrick said. “The tug towed it to shore.”

|

|

At a McGinnis cleaning and drydock facility, welder Chris Wall applies a patch to a deck barge. “We do a little bit of everything. We keep ‘em floatin’.” |

Another unusual sight in the fleets occasionally happens around tank barges used to transport edible oils that ultimately will be ingredients in Cincinnati-based Procter & Gamble Co. food products. “If it’s a kosher product, the barge needs to be blessed by a rabbi,” Hedrick said.

Ohio River barges carry coal, fertilizer, grain, road salt, iron ore, chemicals, steel, scrap metal, aggregate and other bulk products including plenty of petroleum and edible oils. Economic developers in Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana intend to use the newly designated Ports of Cincinnati & Northern Kentucky to galvanize local officials and the public to appreciate and support their waterways’ businesses, said Eric Thomas, co-founder of the Central Ohio River Business Association (CORBA).

The larger, re-designated port includes 70 active terminals and adds a seven-mile stretch of the Kentucky’s Licking River. It becomes the second-largest inland port by cargo tonnage only after Port of Huntington Tri-State, which is No. 1 in part because of the large amount of coal handled there. Due to the decreased use of coal in Midwest power plants, both ports are attempting to identify replacement cargoes to offset recent losses in coal volumes.

|

|

Doug Hedrick, manager of marine operations. |

The re-designation is a recruitment tool for CORBA and its partners, demonstrating to potential employers that the region offers a low-cost, energy-efficient water transportation network that connects easily to rails and highways. The port has even discussed a reciprocal agreement involving the new offshore bulk and container port near New Orleans that would bring the benefits of the Panama Canal expansion to the inland rivers, said Thomas, who is general manager of Benchmark River & Rail Terminals in Cincinnati.

McGinnis, part of the McNational Inc. conglomerate, home-ports its Cincinnati-region boats at its docks at Ohio River mile 480. Six of the vessels work in the harbor full time, and four usually stay on duty at power plants. Most of the company’s towboats are 1,000 hp to 1,200 hp.

McGinnis runs a barge repair and servicing business at its mile 482 cleaning and dry-dock facility. The company’s headquarters are upriver at South Point, Ohio, near the mouth of the Big Sandy River. At South Point, McGinnis recently opened the nation’s most technologically and environmentally advanced inland barge blast and paint facility, which is fully enclosed.