In 1915, Joseph Conrad wrote “The Shadow Line.” First published in a New York City magazine, the novella tells the story of a young deck officer who left a prestigious position on a modern British steamship. In his late 20s he departed the ship in Singapore with no particular plan except to chart his own course. He found what he was looking for as master of a sailing vessel out of Bangkok.

Simon J. Hall, author of “Chasing Conrad,” found himself in a similar position in the 1970s. Having survived the demanding and demeaning rigor of cadet life and completing all the course requirements at the navigational schools, he was a junior deck officer on a tanker. Longing for the exotic life in Conrad’s novels, he made his way to Far East tramp freighters.

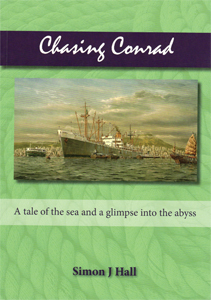

In the decade before containers replaced break-bulk cargo, ships still spent several days in every port. Photos and descriptions of each ship are included in the book. “The Benlawers was built in 1970 as one of the new breed of fast ships for the Far East run, designed to operate as general cargo liners while also being capable of carrying containers,” Hall writes. “The strategy didn’t work, though: These hybrid liners were soon heavily outclassed by purpose-built containerships. This resulted in the new breed being sold off. … In their place, cheaper ancient ships like the Benalbanach were being acquired for the staple Far East liner service. The march of time was relentlessly hunting all these general cargo ships down.”

The author moved from ship to ship, staying ahead of “the march of time” and traveled from port to port, first around Southern Africa and then to the South China Sea. The good life was not only in the prolonged port visits from Durban to Auckland, but also on board the ship where a well-stocked officers’ bar was the norm. Some bars on older ships were converted smoking rooms while others were built to be bars. “There were two fridges, mainly full of beer, one in use and one cooling down the backup stocks,” Hall states. “On the bulkhead behind, a parade of upside-down bottles stood on quarter-gill optics, there was a shelf of glasses caged behind roll bars, a music deck was screwed to the counter.”

Crews were large, and steward service and good food were among the luxuries. “The Benreoch had a good-sized complement, nearly 50 souls … 90 percent were from Scotland,” he writes. “On my side of the business we had the captain, chief officer, first, second, third and fourth officers, plus three cadets.”

These ships had all their own cargo gear for several holds. These required crew maintenance of winches, blocks and cables while at sea. In addition, “every day, day on day, the Chinese painters rose, and they painted, all day every day. The superstructure gleamed white, the decks and working gear were painted a creamy brown,” Hall recalls. “The painters’ pièce de résistance was the (faux) wood painting of the bulkheads.”

As good berths on British-flagged ships declined, the author happily found his way to a Hong Kong-based shipping company: “The cargo pattern on the Poyang was to load up in the big Far East ports of Singapore, Manila, Kaohsiung and Hong Kong, and then steam south and tramp round the islands for several weeks.”

In the times about which Hall writes, it was not unusual for crew and officers alike to bring new acquaintances of both genders on board for visits. While admitting he often drank to excess in his younger days, the author doesn’t hesitate to tell it like it was and to let us all chase Conrad just a little.