On a foggy spring day, the Great Lakes freighter Roger Blough grounded in the St. Marys River near Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., while preparing to overtake a disabled laker under tow. The ship came to rest on the U.S.-Canada border and stayed there for a week before refloating.

At least half of the ship’s 105-foot beam was outside the channel in the moments before the grounding, according to National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators. The second mate did not notice because he was looking out the bridge windows “and not monitoring the track on the electronic chart,” the agency said in its report.

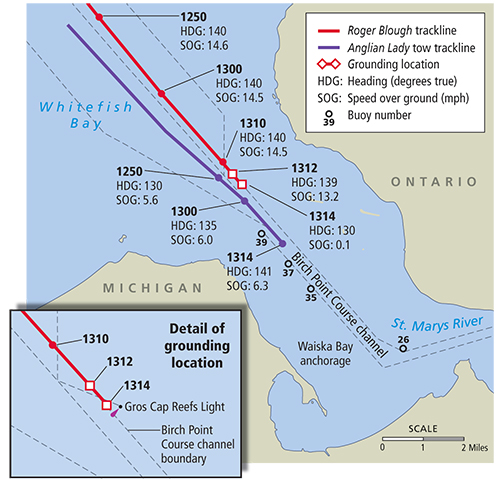

The NTSB determined the second mate’s “failure to use all navigational resources to determine the ship’s position” was a leading factor in the grounding, which occurred at 1312 on May 27, 2016. “Inadequate monitoring” of Roger Blough by Coast Guard Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) St. Marys River also contributed to the incident.

The 858-foot Roger Blough was downbound from Superior, Wis., to Conneaut, Ohio, with a load of taconite pellets. Ninety minutes before the accident, VTS watch standers questioned whether the ship could overtake the tow, which consisted of the disabled laker Tim S. Dool and the 3,500-hp tugboat Anglian Lady.

Nevertheless, at 1211, Roger Blough’s second mate made arrangements with Anglian Lady to overtake the tow, which was then traveling at roughly 5 mph. The laker was making 14.5 mph and hugging the left side of the channel as it approached the tow, which by then had added a second support tug.

Two minutes before the grounding, the tow was moving toward the right side of the channel to let Roger Blough pass. The vessels were within a four-mile section of the river known as Birch Point Course. Roger Blough’s port side was outside the channel, and the ship was starting to slow. The vessel’s draft was about 28 feet.

“At 1312, the Roger Blough passed over a charted 30-foot depth curve near the Gros Cap Reefs,” the report said. “About this time, the vessel hit the bottom … (and it) continued to move forward for two minutes, dragging the hull an additional ship length over the reef’s bedrock until the vessel came to rest.”

Before the accident, Roger Blough’s master ordered the mates to reduce speed to 13.5 mph when approaching Gros Cap Reefs Light, and then cut speed to roughly 11 mph when the ship passed the lighthouse. The second mate acknowledged receiving the order, but he did not follow it “because he intended to overtake the Anglian Lady tow in Birch Point Course,” the report said.

|

|

AIS data shows the tracklines of Roger Blough and the Anglian Lady tow leading up to the accident. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration |

The ship’s hull sustained “multiple punctures and large fractures,” and flooding occurred in the forepeak and several ballast tanks and void spaces. The self-discharging ship’s cargo system also was damaged. Roger Blough refloated a week and a half after the incident after its cargo was offloaded to the laker Philip R. Clarke. The total damage was $4.5 million.

Investigators looked at several factors, including VTS activities and the role that squat played in the accident. Squat is a hydrodynamic force that increases a vessel’s overall draft, and its effects are most pronounced in waterways with narrow channels or shallow water, the report said.

The NTSB could not determine how much squat’s effects contributed to the accident. However, it suggested that squat increased as Roger Blough slowed just before the grounding. In any case, the agency said it “exacerbated the existing dangerous situation” present with the ship sailing over the channel’s edge.

The VTS St. Marys River team consisted of two experienced watch standers on the day of the accident. They did not realize Roger Blough was at risk of grounding until after the accident, the report said. The NTSB determined that the watch standers likely would have seen the ship sailing on the channel’s outer edge “had (they) effectively monitored the vessel’s track.”

The NTSB later suggested VTS watch standers could improve safety by taking a more proactive approach to managing vessel traffic. The agency ultimately made 17 recommendations to the Coast Guard regarding the VTS system, although it is not clear if any have been followed.

A representative at Coast Guard headquarters did not respond to a request for comment about the NTSB findings or recommendations.

Great Lakes Fleet Inc. of Duluth, Minn., owns the 45-year-old Roger Blough, and Keystone Shipping Co. of Philadelphia was its operator at the time of the grounding. A Keystone Shipping spokesman did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the NTSB findings.