The two biggest ferry operators in North America are poised to embrace liquefied natural gas (LNG) as an alternative to marine diesel to fuel their fleets.

Washington State Ferries, whose vessels carry more passengers than any other operator in North America, expects in the coming years to convert six existing ferries to LNG. And BC Ferries, second in North America in the number of passengers carried, expects its next class of new ferries to be fueled by LNG.

“It’s a no brainer for newbuilds,” said Deborah Marshall, the spokeswoman for BC Ferries.

|

|

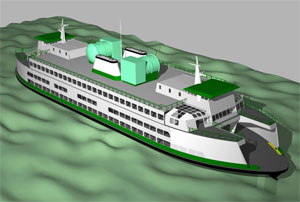

Issaquah, one of the 1,200-passenger ferries being considered for conversion to LNG beginning in late 2014. |

Washington State Ferries and BC Ferries won’t be the first operators in North America to put an LNG-powered ferry into operation. That honor is likely to go to Société des traversiers du Québec, which has ordered a 180-car LNG ferry from Fincantieri that is expected to enter service in late 2014.

Nevertheless, the ambitious new construction and conversion plans by the two big Pacific Northwest ferry companies represent the coming of age of LNG technology in North America. No longer a novelty, it is taking its place in North America as a practical alternative to marine diesel.

“I absolutely agree with that,” said Mark Collins, BC Ferries vice president of engineering. “We don’t see any show stopper. LNG is not a riskier fuel than diesel; it’s a different fuel.”

The director of Washington State Ferries, David Moseley, also believes LNG may be on the verge of widespread adoption as a marine fuel. The reasons for adopting LNG are compelling, he said: “One is cost. One is the environment.”

Burning LNG produces no particulate matter and no sulfur oxides. Nitrous oxides are reduced by about 90 percent compared with diesel fuel, and carbon dioxide emissions are 20 percent less.

The big driver, however, is the dramatically lower cost of LNG. Moseley explained that in 2000, marine diesel fuel represented 11 percent of Washington State Ferry’s operating budget. By 2012 it had soared to 29 percent of the budget, or $67.3 million. And those costs may keep on climbing. “That’s certainly the trend line,” said Moseley, whose official title is Washington State Department of Transportation assistant secretary, ferries division.

Washington State Ferries says that at current prices the fuel cost savings of switching to LNG from marine diesel would be in the range of 40 to 50 percent. So the potential savings are enormous.

Glosten Associates, a naval architecture and marine engineering firm based in Seattle, conducted a study for Washington State Ferries on the feasibility of equipping the ferry company’s next generation of ferries with LNG-burning engines. It found that each vessel could potentially realize operational savings of more than $1 million annually.

|

|

Courtesy BC Ferries Spirit of British Columbia is one of several vessels BC Ferries considers as a possible candidate for conversion to LNG. But first the company expects to build new LNG ferries. |

Washington State Ferries is moving ahead to realize the kind of savings LNG offers. The first step is likely to be the conversion of six Issaquah-class ferries to LNG. These 1,200-passenger ferries were built in the early 1980s. The ferry system has U.S. Coast Guard approval of a conceptual design for converting the vessels to LNG. However, the ferry system must still develop a risk assessment and a plan for mitigating those risks, such as storage and handling of fuel. Operational and security plans must also be developed.

With timely Coast Guard approval and passage of funding by the state legislature, Washington State Ferries would be ready to move ahead with the conversions by late 2014.

If the ferries are converted to LNG, the investment would be paid back in eight years by the fuel cost savings, Moseley said.

Moseley would like to see LNG engines on the ferry system’s newest vessels, but construction schedules may not allow that to happen, at least not right away. The first of three new 144-car Olympic-class ferries is under construction. Work on the second was due to start in early 2013.

If the state legislature approves funding during its next session, then the third ferry will be built with a diesel propulsion system. But eventually the Olympic class could be converted to LNG.

Citing “very tight timing,” Moseley said, “If we get money this (legislative) session and haven’t got Coast Guard approval, we would do (the third ferry) as a diesel and convert to LNG later. That’s the current thinking, possibly convert later to LNG.”

BC Ferries’ plans reverse the sequence Washington State Ferries intends to follow. BC Ferries expects to start with LNG newbuilds and hopes to move on to conversions in the future.

BC Ferries needs to replace three vessels that are to be retired over the next few years (a 50-car ferry in 2016; and two 185-car vessels, one in late 2016 and the other in early 2017).

While no decision has been made, Collins, the BC Ferries vice president, is confident the new vessels built to replace the retired vessels will be powered by LNG. But first the British Columbia government is meeting with community groups to determine what service levels are needed. Based on those discussions, BC Ferries will determine the size and number of vessels needed to meet those service levels.

“They may want multiple smaller rather than fewer large ferries,” Collins said. BC Ferries, for reasons of economy, wants whatever vessels are built to be as much alike as possible. “We strongly prefer multiple vessels of identical designs,” Collins said.

In order to have a new vessel ready to go into service when the first of the old ferries is retired, a design/build contract will have to be awarded in 2013. So when the decision to move ahead is made, it could be for three, four or five vessels, but Collins expects them to be identical and to be powered by LNG.

The economic argument for LNG is very powerful. The incremental cost of new construction for an LNG vessel is 7 to 15 percent over conventional marine diesel vessels, but lower fuel costs will replay that quickly. “You will get that investment back in eight to 24 months,” Collins said.

The payback time for conversions is not nearly so good, eight to 12 years, depending on the complexity of the project. “That’s not a very attractive financial proposition. We’d prefer five to seven years,” Collins said. “We’re very intensely searching for ways to bring down the cost of conversion.”

One of the problems holding back acceptance of LNG has been the availability of fuel, or put another way, the big capital expense of creating LNG fueling facilities. It turns out BC Ferries did not have to solve this problem itself.

FortisBC, a natural gas utility, has an LNG storage facility just south of Vancouver that has been in operation since 1971. Designed to augment supplies of natural gas during periods of peak demand in the Vancouver area, the plant will be a source of LNG for both BC Ferries and Washington State Ferries.

It was FortisBC that approached BC Ferries two or three years ago. The company told BC Ferries, “We can just truck it right out to your ships,” Collins recalled. “We said, ‘Brilliant.’”

BC Ferris was told that a specialized truck could pick up fuel at the Fortis facility and drive to the dock to refuel a ferry. In other words, the ferries would be fueled in much the same way they are now and on much the same schedule.

“It was an epiphany for us. It took away a whole level of complexity.” Collins said. “That was a game changer for us.”

So availability of LNG has not proved to be a problem. According to John F. Hatley, Americas vice president ship power with Wärtsilä, one of the world’s leading makers of LNG-fueled marine engines, “LNG is abundant, available and affordable.”

And that means LNG can take center stage as a clean, affordable alternative to marine diesel.

—–

Editor’s note: Mark Collins was BC Ferries vice president of engineering when he was interviewed by Professional Mariner in early November. He has since left the company.