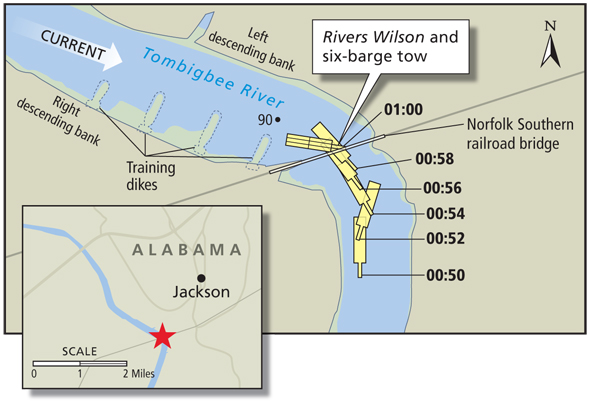

Rivers Wilson was pushing six barges up the rushing Tombigbee River when its port-side aft barge hit the Norfolk Southern railroad bridge near Jackson, Ala. The tow spun to port after impact and became pinned against a support pillar.

The collision, at about 0100 on March 10, 2019, pushed the bridge at mile marker 88.2 out of alignment. Railroad officials closed the span to train traffic for more than a day. Permanent repairs cost more than $4.8 million. One crewmember fell and suffered a minor injury in the minutes after the bridge strike.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators acknowledged the Tombigbee was in flood stage, and they also recognized that the bridge opening — located along a bend — is poorly aligned with the river current. That said, the agency cited the pilot’s decision to continue the voyage through the bridge, given his unfamiliarity with Rivers Wilson, as a leading factor in the allision.

“(The pilot’s) incomplete understanding of the current, in combination with the misalignment of the bridge with the thalweg and Rivers Wilson’s lower horsepower (than his usual) vessel … resulted in his belief that the tow had enough speed to overcome the effect of the current,” the NTSB said in its accident report.

After the bridge strike, investigators identified numerous deficiencies with the 2,800-hp towboat built in 1958, including watertight and structural integrity issues. The vessel did not have a certificate of inspection or meet Subchapter M standards.

The Coast Guard detained Rivers Wilson for some time afterward, and the NTSB said it had not returned to service by spring 2020 when it published the accident report.

Graestone Logistics of Mobile, Ala., owned and managed Rivers Wilson, but personnel from Parker Towing of Tuscaloosa, Ala., crewed the vessel at the time of the bridge strike. Neither company responded to inquiries about the NTSB findings.

Rivers Wilson departed a fleeting area near Mobile at 2040 on March 8 with six barges, each carrying about 1,600 tons of direct reduced iron. The destination was Nucor Steel in Tuscaloosa. The original plan called for eight barges in the tow, but the captain opted for six because it was his first trip with Rivers Wilson, the NTSB reported. The captain and the pilot had worked together for several years on a 3,800-hp towboat in Parker’s fleet.

River conditions likely influenced his decision. Opinions among the crew varied, although the pilot said the Tombigbee was the highest he could recall during 11 years with Parker Towing. A gauge located about a mile from the Norfolk Southern bridge in Jackson registered 29.4 feet, or 5.4 feet above flood stage.

|

|

The positions of the tow before the impact. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration |

The voyage upriver had occasional hiccups along the way. Twice the towboat “bogged down” in the current and dropped from about 3.5 mph to 1.5 mph. Crew also had to stop and fix an oil leak on the starboard main engine on March 9. The pilot estimated the current at about 8 mph for much of the voyage.

The pilot, with 28 years of industry experience, came on watch at 2300 that night. He prepared to abort the tow, if needed, downriver from the Norfolk Southern bridge if Rivers Wilson struggled to maintain speed upriver. But as the tow approached the abort point at about 2400, the vessels continued upriver at around 3 mph. The tow approached the rail bridge at about 0050 the next morning.

“The bridge tender noticed the (towboat) was slowing as the tow passed under the bridge and asked the pilot if he was about to ‘stall out,’” the report said, noting that the tow was moving to port at 1.5 mph with no forward movement at all.

“The bridge tender radioed that the pilot would have to ‘make it smoke black to get up through there,’ to which the pilot replied, ‘Looks like I may be fixing to touch up on you, too,’” the report continued.

He was right. TOUAX 956 B, the aft port barge in a two-wide, three-deep configuration, hit pier 3 on the railroad bridge at 0058. The tow pivoted to port and the current pushed against its beam, pinning the vessels against the bridge. The forward port barge, PTC 851, also hit the bridge. Two good Samaritan vessels helped free the tow.

Rivers Wilson attempted to complete the voyage to Nucor with two loaded barges and two empties. The empty barges were not explained in the report. There is no indication any of the barges spilled their loads or broke away. Regardless, the tow never made it; its port engine suffered a block failure a dozen or so miles upriver from the bridge. The tug limped back to Mobile on a single engine.

The Norfolk Southern railroad bridge is something of a trouble spot on the Tombigbee. Tows hit the 71-year-old lift bridge at least four times between January and March 2019 during high water. The rail company asked the Coast Guard twice in March to close the waterway due to difficult conditions.

The span crosses near the center of a bend that has become sharper over the years. Four training dikes installed just upriver from the bridge two years earlier to stabilize the channel contribute to the challenging current.

That change hasn’t gone over well. The bridge tender told investigators he has heard complaints about the dikes’ effect on the current, and Rivers Wilson’s pilot reported similar issues to the NTSB. The dikes, he said, “forced the current across the river into a sandbar that previously had to be dredged annually. The current then deflected back into the channel at the bridge. The current had always set vessels toward the right descending bank, but the dikes made the situation worse.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a study in 2015 recognizing challenges passing through the railroad bridge. Issues include the location of the bridge relative to the bend, the presence of a growing upriver sandbar, and bridge piers that are poorly aligned with the upstream current. Maneuvering through the area was often difficult, the Army Corps report said, and in high water “the difficulty increases substantially.”