The loss of shipping containers from a Young Brothers deck barge last summer off Hawaii’s Big Island stemmed from insufficient loading practices at the company’s Honolulu cargo hub, federal investigators said.

Fifty containers loaded on the aft deck of Ho’omaka Hou collapsed and 21 fell overboard on June 22, 2020 while under tow to Hilo by the tugboat Hoko Lua. Eight containers were recovered and 13 remain missing.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) attributed the collapse to Young Brothers “not providing the barge team with an initial barge load plan, as well as inadequate procedures for monitoring stack weights, which led to undetected reverse stratification of container stacks that subjected the stacks’ securing arrangements to increased forces while in transit at sea.”

The barge team “consistently” stacked containers with heavy weights atop containers with lighter weights, the NTSB said in its accident report. Seven of the 10 stacks in the toppled row had vertical centers of gravity closer to the highest possible center of gravity for the stack.

In describing the physics involved, the NTSB said “reverse stratification results in stacks having a higher center of gravity than stacks created by placing the heaviest containers on the deck, with progressively lighter containers above — referred to as normal stratification.”

“An initial barge load plan showing stratified container weights would have been a useful tool to assist the barge team machine operators in stacking containers on the barge to reduce or eliminate reverse stratification,” the report said.

Two days before the accident, on June 20, the Young Brothers barge team in Honolulu drove cargo aboard the 340-by-90-foot Ho’omaka Hou and secured the stacked containers with lashings and locking and stacking cones. Dry and refrigerated containers, ISO tank containers, wheeled vehicles, flatracks and palletized cargo were stowed facing fore and aft and athwartship across the beam.

The 40-foot containers in the toppled row of 10 stacks faced fore and aft on the stern, stacked five high except for a four-high stack on the starboard side. Weighed by their shippers, the containers’ gross weights were chalked on their sides and visually inspected in the yard.

Machine operators acknowledged to investigators that the general rule was to stack lower-weight containers on top of heavy containers. “However, numerous barge team members stated that heavy containers could be loaded over light containers if some ‘heavies’ came into the yard after the lighter containers had already been loaded,” as they had in the past, the report said.

A barge superintendent told investigators load planning was done “as the day goes on,” so an initial barge load plan wasn’t prepared for the loading team.

There are no regulatory requirements for loading and securing cargo on unmanned barges, and the Ho’omaka Hou did not have a cargo securing manual, nor was it required to. Stacking heavy containers over light containers can be done but calculations are needed to ensure a secure arrangement, investigators said.

The barge superintendent finalized the stow plan at 1830 that evening and told the company dispatcher it was ready to depart. This plan included the locations of containers but did not show their weights, the report said. Hoku Loa got underway with Ho’omaka Hou at 2028 with six crew for a scheduled 32-hour voyage.

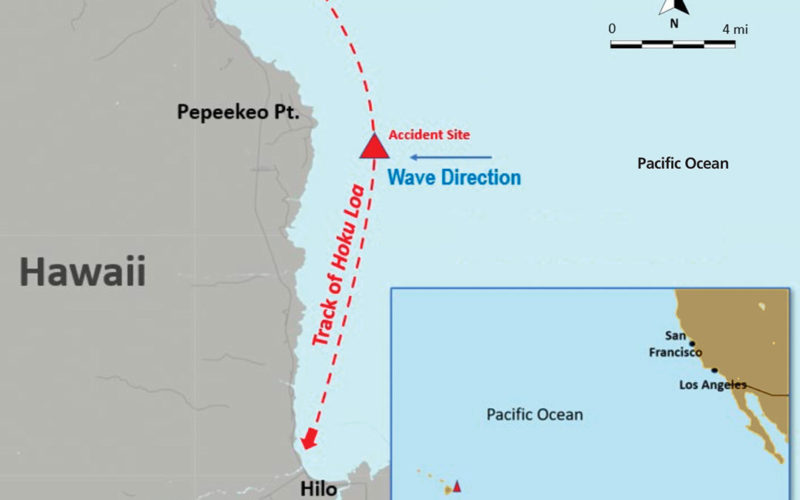

At about 0000 on June 22, the tug and barge were about 12 miles north-northwest of Pepeekeo Point on a 128-degree course when a nearby weather buoy recorded steep seas from the east with 6-foot waves. The vessels reportedly starting rolling following a turn to the south-southeast at 0200 for the final approach into Hilo. Investigators said the container stacks with the greatest reverse stratification likely toppled over following this course change from forces produced by “dynamic rolling from the seas” on the barge’s beam.

No one knew the containers had collapsed until an assist tugboat notified the captain near Hilo. Eight of the 21 containers that fell overboard were salvaged about 3 miles off Pepeekeo Point, roughly 10 miles north of Hilo.

Investigators said it’s unlikely a structural failure caused the collapse. The containers’ corner casings could withstand more compressive force than the weight of each stack. An inspection showed no problems with fixed securing points. And the concrete deck showed no significant scraping from sliding containers to indicate a lashing gear failure.

The cost of the lost and damaged cargo was estimated at more than $1.5 million. Repairing and replacing the recovered and lost containers cost $104,885. Damage to the barge was estimated at $25,000.

Young Brothers, a Hawaii interisland cargo company based in Honolulu, did not respond to a request for comment.

Professional Mariner received the following statements from Young Brothers LLC on Aug. 31,

after the original article went to press:

| The following statement may be attributed to Jay Ana, president, Young Brothers, LLC: | ||

| “Young Brothers is proud of our record of safely transporting what matters most to Hawai‘i for more than 120 years in some of the most challenging sea conditions in the world.

“After the first loss of containers overboard in 20 years, we took immediate action to add new safety measures and enhance the protocols that keep our team members and customers’ cargo safe.”

|