Investigative hearings have revealed details about events leading up to the loss of El Faro, including the deteriorating condition of the ship’s boilers and the fact that no weather routing service was in use.

The U.S. Coast Guard heard nine days of testimony in Jacksonville, Fla., in February. More than two dozen witnesses, many from ship operator TOTE Maritime and the Coast Guard, offered new information about the ship’s mechanical condition and potential engine problems that caused it to lose propulsion.

Authorities discussed stability issues caused from potentially improper loading before the ship departed Jacksonville and a lack of communication with the home office while en route to San Juan, Puerto Rico. No clear reason for the disaster emerged from the hearings, however.

El Faro, a 790-foot roll-on/roll-off cargo ship, lost propulsion and sank on Oct. 1 roughly 35 miles from Crooked Island as the Category 4 Hurricane Joaquin approached. Twenty-eight sailors and five Polish contractors died in the accident, the worst for a U.S.-flagged ship since the disappearance of SS Poet in 1980.

Glen Jackson, whose brother Jack Jackson died in the accident, said he entered the Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hearings with low expectations and did not believe the process would yield the cause of the sinking. He left feeling confident in the Coast Guard investigation but troubled by what he considered TOTE’s efforts to blame ship Capt. Michael Davidson for the accident.

Jackson, who traveled from New Orleans to attend the hearings, said he was bothered by apparent inconsistencies from TOTE officials and shortcomings in the company’s safety systems, including the lack of a weather routing service aboard El Faro.

“I found it absolutely appalling that they wouldn’t give all of their captains plying all over the world something that essential for such a small cost,” he said in a phone interview, noting that the company said it has since installed weather routing on its ships for $750 a month per vessel.

The Coast Guard convened the Marine Board of Investigation hearings from Feb. 16 to Feb 26 in Jacksonville to answer three basic questions: what caused the sinking, whether failure of materials or design require new safety recommendations, and whether any licensed or certified personnel on board the ship broke the law, acted improperly or neglected their duty.

The five-person Coast Guard panel will reconvene later this year to continue the investigation. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is conducting a separate probe into the incident. The NTSB announced earlier this year it would launch a new search in April for the ship’s voyage data recorder.

The recently concluded Coast Guard hearings featured several dramatic moments, including the publication of phone calls from the stricken ship to the home office. In a voicemail message left for Capt. John Lawrence, the designated person on shore for TOTE, Davidson said a scuttle was open and the vessel was taking on water.

Later, when speaking with a company operator, Davidson appeared frustrated by the lack of urgency.

“Oh man,” he said, when asked to spell the vessel’s name, according to transcripts the Coast Guard released. “The clock is ticking. Can I please speak with a QI” — the name for the designated person on shore.

After waiting on hold, Davidson carefully explained the nature of the emergency to the company operator.

|

|

Phil Morrell, vice president of operations for TOTE Maritime, was one of several company officials and former crew called to testify. |

|

AP pool photos/Florida Times-Union/Bruce Pipsky |

“We had a hull breach. A scuttle blew open during a storm. We have water down in 3-hold with a heavy list. We’ve lost the main propulsion unit. The engineers cannot get it going,” he said. “Can I speak with a QI please?”

After speaking with Davidson on an unrecorded line, Lawrence contacted the Coast Guard. At the time, the agency did not believe the vessel was at risk of sinking. The watch stander who took Lawrence’s call suggested El Faro could drop anchor. He also said it was up to TOTE to arrange a tugboat assist.

The watch stander testified that he became alarmed after seeing El Faro’s distress signal. He called El Faro via satellite phone but never reached the crew.

The Coast Guard panel spent considerable time discussing the condition of the 40-year-old ship. Witnesses revealed that El Faro was to be included on a Coast Guard list of troubled U.S.-flagged vessels inspected by the American Bureau of Shipping through the Alternate Compliance Program. Inclusion on the list would have required a stringent Coast Guard investigation.

During testimony, Jim Fisker-Andersen, TOTE Services’ director of ship management, acknowledged that a September survey showed “cracking and loss of material, plus heavy buildup of fuel” in all three burner throats in El Faro’s starboard boiler. Despite severe deterioration of certain boiler components, Fisker-Andersen said boiler experts believed the repairs could wait until the next dry dock.

Former El Faro chief engineer James Robinson also testified that the boiler repairs were not urgent. He suggested that the boilers might not have been responsible for the mechanical issue that disabled the ship.

“If he was talking (about) the propulsion, that would be the reduction gear and the turbines,” Robinson said when asked about the nature of Davidson’s distress call.

“You lose a turbine, you’re done. You’re not going to get propulsion back,” he said, adding that he had never before seen a ship lose a turbine.

Early into the hearings, TOTE officials testified that there was limited communication between the home office and El Faro after it departed Jacksonville, even as the vessel approached Hurricane Joaquin. They argued that Davidson had sole authority over the ship’s route.

“The authority for voyage planning resides with the master,” Phil Greene, president and chief executive of TOTE Services, testified. “It’s at the master’s discretion to determine the best track.”

Lee Peterson, TOTE’s director of safety and marine services, testified that he was not monitoring Hurricane Joaquin as it churned into the Caribbean. He wasn’t sure if anyone else from the company was keeping tabs on its path or proximity to El Faro.

Davidson steered El Faro on a longer route west of the Bahamas to avoid Tropical Storm Erika on a similar run from Florida to Puerto Rico in August. Peterson said he wasn’t sure why Davidson did not make a similar decision on the ship’s final voyage.

TOTE officials revealed Davidson earned high marks on regular performance reviews, and Fisker-Andersen described him as a very effective captain. An attorney for Davidson’s widow noted that the storm was 100 miles off its projected track.

|

|

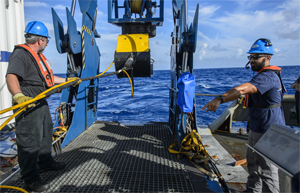

Contractors recover the Orion side-scan radar unit aboard the tugboat USNS Apache during the search for El Faro near the Bahamas in October 2015. The National Transportation Safety Board planned a new search in April to recover the voyage data recorder. |

|

Courtesy U.S. Navy |

The hearings revealed discrepancies between CargoMax loading software used to plan the loading of vehicles, containers and other cargo about the ship. At one point, the ship’s draft line was said to be off by 10 inches forward and 3 inches aft compared to the program’s projections.

Jacksonville maritime attorney Rod Sullivan, who attended the hearings, said those details raised fresh questions about the ship’s stability.

“It is an open question: Did the vessel sink because it was unstable because of how it was loaded?” Sullivan said in a phone interview.

He believes the hull breach that Davidson mentioned to company officials was worse than many experts thought. Rather than just an open scuttle hatch, Sullivan suggested cargo could have broken free and punched a hole in the hull.

“Nobody believes water was flooding into the scuttle hatch in second deck and filling hold No. 3,” Sullivan said, noting that the hatch was 12 feet above the waterline. “The hatch isn’t that big.”

Sullivan is acting as local counsel in an ongoing lawsuit against TOTE filed by the estate of Sylvester Crawford, an engineer aboard the ship. Sullivan believes TOTE officials intentionally tried to pin the accident on Davidson to limit or avoid liability for the lost cargo.

“The idea was, while he was still alive he was a great captain and did a great job and was a proud part of the TOTE fleet. But once the ship sank, they brought out a bunch of negatives,” Sullivan said.

In a statement, TOTE spokesman Michael Hanson did respond to Sullivan’s claims.

“From the beginning we have been fully committed to supporting the NTSB and USCG investigations and will continue to contribute maximum cooperation going forward,” he said. “Our goal throughout the process has been to learn everything possible about the tragic loss of our crew and vessel. We welcome any safety-related advice from these investigations that benefits all seafarers.”

Hanson said TOTE Maritime does not comment on its individual employees but has “great confidence in its highly experienced officers and crew.”

Jackson said his brother Jack, 60, was a U.S. Navy veteran who began working for TOTE about nine months before the accident after a long career as an able seaman. At the time, he was thrilled to find work with less time at sea.

“He was a great guy,” Jackson said. “He was a wonderful brother and a really good man and a very, very capable salty sailor. I miss him terribly.”

He hopes the former El Faro crewmembers not currently employed by TOTE will be asked to testify when the Coast Guard panel reconvenes. He hasn’t given up hope that authorities will find out what caused El Faro to sink.

“I am certainly hoping the VDR is recovered because there is still so much that isn’t known,” he said.