The latest Seafarers Happiness Index found the lowest levels of fulfillment among oceangoing mariners since the project launched in 2015.

“Seafarers continue to work with dedication, professionalism, care and resolve,” according to the quarterly index compiled by Mission to Seafarers. “However, many are facing a time like never before, with a pandemic, a war and commercial decisions all impacting them.”

The report gathered responses from mariners across the globe primarily through anonymous online surveys. It measures satisfaction on a 10-point scale. For the first quarter of 2022, overall work happiness averaged 5.85, down from 6.41 in the last quarter of 2021. The survey also had a written portion, where respondents could elaborate on their feelings.

“It gives us a snapshot of the sentiment on board vessels,” Steven Jones, the report’s editor, told Professional Mariner. “It gives us a kind of direction of travel, of how things and issues are affecting those at sea, and we try to kind of use the data as a hook to start a conversation.”

Contentment dropped in survey questions asking about nearly all facets of ship life. Happiness around interaction with other crew dropped, as did answers involving contact with family, workload and access to shore leave.

Much of this frustration can be traced to stresses caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. “Every part of what it has traditionally been to be a seafarer has been impacted by the pandemic,” Jones said, “and all of it in a terribly negative way.”

The pandemic continues to delay crew changes, Jones said, sometimes leaving ships shorthanded. It has also restricted shore leave and created stress when people come on board, raising anxiety that they could carry the virus with them.

American bluewater sailors tend to be happier than their international counterparts because their pay is higher and assignments are shorter, said Rev. Mark Nestlehutt, president and executive director of the Seaman’s Church Institute. But longer assignments, spurred by the pandemic, have taken a toll.

“For the first time, you had seafarers on tours of 11 months that went on for 24 months,” he said. “So, you miss not just one but two anniversaries, not just one but two birthdays. A lot of the pressure comes from home.”

Seafaring is one career where people of various internationalities work side by side, so the geopolitical conflict created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has bled onto ships. In written responses, some mariners said they “were struggling to work with crews containing Russian seafarers.”

“We heard some reports of masters and chief officers unable to exchange work-related information or refusing to speak to each other,” the report notes. “That has a very concerning implication not only for social cohesion on board, but safety too.”

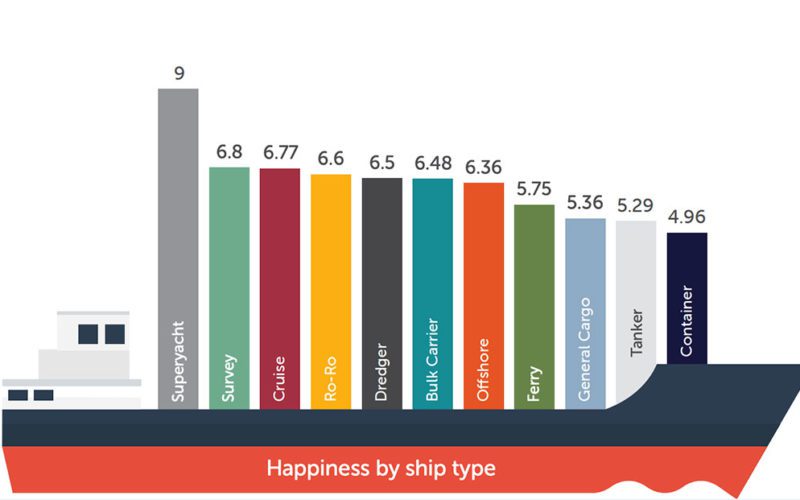

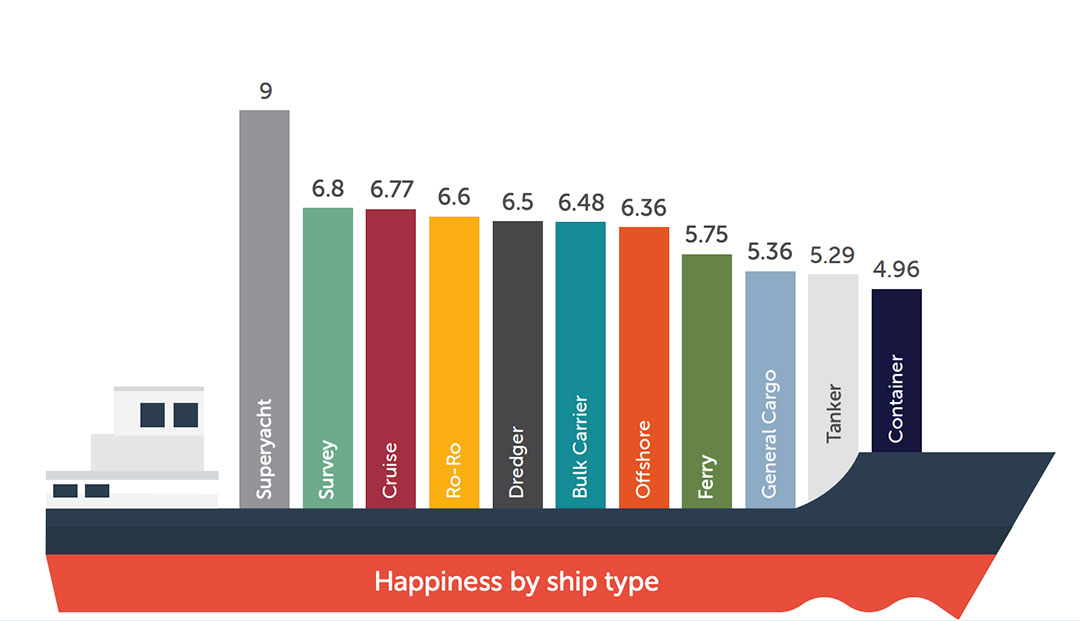

Feelings of contentment, misery and “meh” are not spread evenly across the maritime industry. The report found some differences based on ship type, rank and age group.

Crewmembers working aboard large yachts reported the highest satisfaction overall. On average, they rated their job satisfaction at a 9 out of 10. The workers on general cargo ships, tankers and container vessels rated their happiness the lowest.

Older seafarers were generally happier. Those 55 to 65 years old rated their happiness at 7.06 out of 10, and those over 65 averaged an 8 out of 10. Jones chalks this up to more fine-tuned coping mechanisms and the sense that if someone keeps doing a job past their late 50s, they are probably content with it.

As for ranks, the happiest were the catering department (who rated theirs at 7.12 out of 10), deck crew (6.8) and captains (6.72). The lowest were chief officer (4.86), second engineer (4.7) and electrical department (3.58).

The 5 percent of female respondents were about as happy as the 94 percent who identified as male, with average scores of 5.64 to 6.

Although the atmosphere for female seafarers can be “difficult and challenging,” Jones said shipping companies have worked to close the happiness gap. “Obviously, the reality is that it is such a hugely male-dominated profession and there are lots of great initiatives to try to turn that around, to try to attract more women into maritime roles, particularly to working at sea. I think they are starting to bear fruit.”