Federal investigators determined a ship pilot’s decision to overtake a slower-moving towboat within a riverbend during high water was the leading cause of a grounding on the ower Mississippi River.

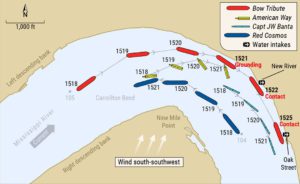

The downbound tanker Bow Tribute was attempting to pass the 2,000-hp American Way and its two-barge tow within Carrollton Bend near mile 104 when it touched bottom near the left descending bank. The 599-foot ship then struck two fenders protecting New Orleans water and sewer system intakes more than a quarter-mile apart.

The downbound tanker Bow Tribute was attempting to pass the 2,000-hp American Way and its two-barge tow within Carrollton Bend near mile 104 when it touched bottom near the left descending bank. The 599-foot ship then struck two fenders protecting New Orleans water and sewer system intakes more than a quarter-mile apart.

No one was injured and there was no pollution in the incident, which happened on March 16, 2021, at about 1520. But damage to the ship and water system infrastructure exceeded $1.9 million.

Citing the 3.5-knot following current and high water, National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators said the New Orleans-Baton Rouge Steamship Pilots Association (NOBRA) pilot conning the ship had options to prevent the incident.

“(The) NOBRA pilot could have reduced (the ship’s) speed before the bend, given the number of other vessels rounding the point,” the NTSB said in its report. “At a slower speed, the tanker could have then overtaken American Way after the bend … in an area where both vessels would have been on a relatively straight course.”

Ineffective communication between the NOBRA pilot aboard Bow Tribute and the pilot helming American Way about where the ship would overtake the tow contributed to the incident, the NTSB said.

NOBRA declined to comment on the NTSB findings. American Commercial Barge Line, which operates American Way, did not respond to an inquiry before press time.

The Norway-flagged Bow Tribute got underway in ballast from a terminal near Baton Rouge at about 0900. The pilot guided the ship downriver with a following current of about 3.5 knots. The voyage was uneventful until about 1500 when the ship approached Nine Mile Point, a landmark within Carrollton Bend just west of New Orleans.

The 70-foot American Way was 3 miles ahead, pushing two empty 298-foot barges positioned side by side, when the NOBRA pilot aboard Bow Tribute hailed the towboat. He proposed meeting at Nine Mile Point and later clarified the ship would overtake the tow “on the two,” meaning the tanker’s starboard side.

The ship was traveling at about 15 knots while the tow made about 8.5 knots, pushed by the current. The river was at 12 feet and rising, which is considered high water. Several other vessels were operating nearby, including the upbound bulk carrier Red Cosmos. Another tow pushed by Capt. J.W. Banta was just ahead of American Way.

American Way sped up at the NOBRA pilot’s request, meaning the overtaking maneuver would occur as the vessels rounded Nine Mile Point. The pilot aboard Bow Tribute tacitly acknowledged to an observer on the ship’s bridge that the situation was not ideal.

“I don’t like to do this, but we got to. We have no choice,” the ship pilot said, according to the NTSB report.

The z-drive American Way began its turn around the point from the middle of the river but slid toward the left bank as it maneuvered around the bend. This reduced the amount of space Bow Tribute had to pass the tow.

“You’re gonna make it, huh?” the pilot on Bow Tribute asked American Way’s pilot over the radio at 1519, when the vessels were 0.15 miles apart.

“You gonna be alright?” the ship pilot asked moments later, according to the report. “You gotta drive on that thing, man,” the ship pilot said less than a minute later.

American Way’s pilot acknowledged he was trying to straighten out the tow, but within 30 seconds it had slid farther into the ship’s path. The ship pilot recognized the developing situation and asked that the anchors be ready to let go.

About this time, American Way’s pilot summoned the captain to the wheelhouse. He assumed control and began steering toward the center of the channel.

American Way’s stern was roughly 130 feet from Bow Tribute’s starboard bow at 1520. The ship pilot ordered the engine to astern and gave helm orders intended to avoid a collision. He also sounded the ship’s whistle and requested tugboat assistance.

“The NOBRA pilot on Bow Tribute, not wanting to collide with the American Way, told investigators that he kept the vessel near the shoreline because he could no longer see American Way under Bow Tribute’s starboard bow,” the NTSB report said.

At mile 104.1, Bow Tribute’s port quarter hit a spud barge installed to protect river intakes for the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans. Three minutes later, at 1525, the ship hit another spud barge protecting an intake system at mile 103.8.

One spud barge broke free and drifted downriver. A catwalk and other water intake infrastructure sustained damage. Bow Tribute’s portside hull aft and its propeller required repairs. American Way was not damaged and it continued to its destination.

American Way’s captain and pilot said overtaking maneuvers were rare in Carrollton Bend because downbound tows often slid toward the bank. The NOBRA pilot disputed that, suggesting such moves were common and that in this scenario, the upbound Red Cosmos, the American Way tow and Bow Tribute each would have had a third of the river to operate. Still, investigators said the crowded waterway and fast-moving current left little room for error.

American Way’s pilot also told investigators he expected to be overtaken after the bend, not within it. That confusion could have been addressed by either party over the radio well before either vessel found itself in danger of a collision.

“Clear, effective and unambiguous radio communications should be used,” the NTSB said in its report, “especially during high traffic and dynamic conditions such as overtaking in a bend.”