Interlake Steamship builds flexibility into first US laker in 40 years

The Interlake Steamship Co. has been moving freight on the Great Lakes for generations. Its newest ship, Mark W. Barker, will build on that tradition for years to come.

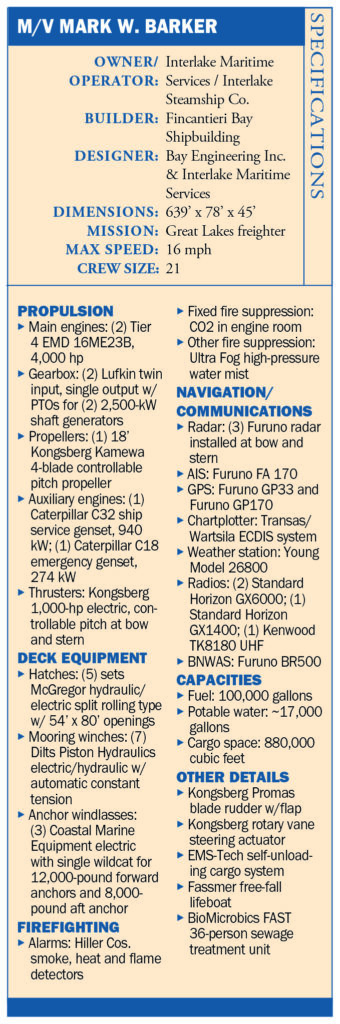

The 639-by-78-foot Mark W. Barker is the first U.S.-flagged Great Lakes freighter built in almost 40 years, and it’s the first ship operating on the Lakes with EPA Tier 4 engines. The self-unloading bulk carrier is the lead ship in Interlake’s River class.

Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding built the steel-hulled ship using a collaborative design from Bay Engineering Inc. and Interlake’s in-house engineering department. The ship was designed around a flat-bottomed cargo hold that increases capacity and versatility compared to a traditional laker outfitted with sloped holds. Load-bearing hatch covers above deck can carry windmill parts and shipping containers.

“This box-shaped cargo hold allows the ship to carry cargoes that may not traditionally move on the Great Lakes,” Mark W. Barker, president of Interlake Steamship and the ship’s namesake, said during its christening on Sept. 1 in Cleveland. “It is important that we can move new types of cargo to meet the changing supply chains of the future.”

Interlake Steamship is the largest privately held American shipping company on the Great Lakes. The company operates 10 ships, four of which are more than 1,000 feet long. The 1,013-foot Paul R. Tregurtha, as the longest active freighter on the Great Lakes, carries the title “Queen of the Lakes.” Mark W. Barker is Interlake’s first new ship since the late 1970s.

Based just outside Cleveland in Middleburg Heights, Ohio, Interlake Steamship can trace its shipping roots to the late 1880s. Chairman James R. Barker took the firm private in 1987 and led it for another 20 years before his son, Mark W. Barker, succeeded him as president. These days, the company transports a wide range of bulk cargo that includes iron ore, stone, coal and salt.

Planning for what became Mark W. Barker started almost seven years ago with preliminary discussions between Interlake and Cargill Deicing Technology. That company extracts roughly 4 million tons of salt each year from a Cleveland mine running under Lake Erie. The salt is used in the winter to clear snow and ice from the region’s roadways.

Those discussions intensified about five years ago. Ian Sharp, Interlake’s director of engineering for fleet projects, and Eric Helder, its naval architect/marine engineer, developed an initial design capable of carrying multiple cargoes, including salt. Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding and Bay Engineering, both of Sturgeon Bay, Wis., adapted those plans further.

spacious bridge.

The resulting ship is one designed for maximum versatility now and into the future. Mark W. Barker is one of Interlake’s shortest ships. That was intentional to ensure it could navigate the Old River channel in Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River leading to the Cargill salt mine. The ship’s relatively compact size and forward unloading boom allow it to dock at Great Lakes ports of all sizes.

The hull form is a mix of old and new. Travis Martin, president of Bay Engineering, said the ship’s rounded bow is reminiscent of other ships that have long sailed on the Great Lakes. Its stern was fine-tuned for maximum efficiency and water flow to the propeller and rudder.

“There was optimization done on the aft end. There was a CFD analysis Kongsberg prepared for Interlake to evaluate flow dynamics at the stern,” Martin said, using a shorthand for computational fluid dynamics. “But forward of the aft machinery space, it is very similar to proven designs.”

Most lakers are built with a V-shaped cargo hold that uses gravity to feed cargo onto the conveyor at the bottom for unloading. That type of system speeds cargo discharge, but at the cost of reduced capacity within the holds. Mark W. Barker’s square holds can carry over 29,000 long tons of cargo at its summer load line — roughly 20 percent more than a similarly sized laker.

EMS-Tech of Belleville, Ontario, designed and delivered the hydraulically operated self-unloading system consisting of 34 basket gates with local and remote-control capability. The conveyor system carries dry cargo forward to the bow, where it is discharged from a 260-foot boom that can be rotated 90 degrees to port or starboard. The highly automated system can be controlled by a single crewmember. Control rooms for the unloading system are located forward and aft.

Gravity ensures most cargo falls into the conveyor system. Two Caterpillar front-end loaders and a Caterpillar skid steer loader push any remaining material into the conveyor system for unloading. The loaders are stored in dedicated garages when not in use.

The MacGregor split cargo hatches represent another innovation for Great Lakes shippers. There are five sets of hydraulic-electric split covers that can be configured in myriad ways to facilitate loading. The system can effectively stack one 50-ton cover on top of another and then maneuver the covers forward or aft on rails, creating 54-by-80-foot hatch openings. Finished steel, 40-foot containers and a wide range of other oversized cargo can be loaded through openings of that size. The hatch cover system can be operated by a single tablet computer.

“The forward leaf is raised by hydraulic lift cylinders and then the aft leaf, mounted on electrically driven wheels, is moved under the raised leaf, which can then be lowered onto the bottom leaf,” Barker chief engineer Erik Wlazlo explained. “Then you can drive the stacked leaves back and forth.”

Deck equipment consists of seven Dilts Piston Hydraulics mooring winches and three Coastal Marine Equipment electric anchor windlasses rated to raise the 12,000-pound forward anchors and the 8,000-pound aft anchor. Fassmer supplied the free-fall lifeboat and rescue boat.

Wlazlo, who came off the 806-foot Honorable James L. Oberstar, has been involved with Mark W. Barker since it was still under construction in Sturgeon Bay. All those hours gave him a strong baseline knowledge of the new ship, which is mechanically different than other Interlake vessels.

The propulsion system is just one example. Mark W. Barker is powered by two 4,000-hp EMD engines that use a selective catalytic reduction (SCR) system to meet EPA Tier 4 emissions rules. Kongsberg supplied 1,000-hp bow and stern thrusters that assist with docking maneuvers. The ship cruises at around 13.5 knots fully laden.

Tier 4 emissions standards.

The main engines are connected to a Lufkin combining gearbox that turns a steel shaft connected to a single 18-foot, four-blade Kongsberg controllable-pitch propeller forward of a Kongsberg rudder. Power take-offs from the gearbox drive a pair of 2,500-kW shaft generators that produce plenty of power to run the cargo unloading system and other operations. A Caterpillar C32 engine drives a 940-kW generator for ship service power, and a Cat C18 drives a 274-kW emergency generator.

The ship’s propulsion plant and auxiliary systems are designed and classed for unmanned engine room operation, which allows complete control and monitoring from the pilothouse.

Hiller Cos. supplied an advanced fire, smoke and heat alarm system installed throughout the ship. The engine room is protected by a fixed CO2 system supplemented by an Ultra Fog high-pressure water mist system.

Wlazlo, who joined Interlake 27 years ago and has overseen steam-to-diesel conversions on other ships, said he and other engineering personnel were still acclimating to Mark W. Barker. As the company’s first newbuild in decades, it has new systems, new technology and new ways of doing things.

“This is just completely different for everybody,” he said. “It’s the same thing with the deck department — we are all learning together.”

On the other hand, he noted the ship’s myriad safety features, modern components and improved design represent a significant step forward. Gone are the days of reaching or crawling into dark nooks and tight corners on the ship, he said.

Interlake Steamship looked to suppliers close to home for much of the ship’s outfitting. It was built using ore that originated in Minnesota mines and was later made into steel at Cleveland-Cliffs’ plant in Indiana. Another Cleveland company, Sherwin-Williams, supplied coatings for the ship’s hull, cargo holds and other exposed spaces.

Mark W. Barker left Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding on July 27 with 21 crewmembers for its maiden voyage to Port Inland, Mich., where it loaded stone bound for Muskegon, Mich. The vessel made nine port calls in its first month, voyaging as far east as Buffalo, N.Y., and as far west as Duluth, Minn.

Interlake selected Capt. Paul Berger, formerly of the 1,004-foot Mesabi Miner, to lead the ship during initial operations. Berger offered high praise for the ship, which features numerous upgrades compared to the older vessels in the fleet.

Those upgrades include a much larger wheelhouse outfitted with floor-to-ceiling, forward-facing windows. There are also wing stations overlooking the port and starboard sides, offering better vantage points during critical docking maneuvers than other lakers. Port and starboard cameras allow for unobstructed views down the length of each side of the ship

“(One of the) nice features for me when maneuvering at the docks is the windows that go all the way to the floor. Boy, can you see,” Berger said. “We have cameras that show everything you would want to see. But I am old-school. I like to look out the window.”

Berger also highlighted the ship-wide public address system that reaches to the deck. The system lets him communicate with everyone on the vessel by pressing a single button.

Mark W. Barker is outfitted with a host of modern navigation electronics. These include a Transas/Wartsila electronic chart display and information system (ECDIS); Furuno radars, AIS and GPS; Young weather stations, and Standard Horizon radios.

“The maneuverability of this ship is excellent,” Berger said. “The thrusters are very capable of handling this size ship. The other thing we have is a flapped rudder that acts like flaps on an airplane wing to provide extra lift. And hard-over rudder is 65 degrees. So, we have a lot of rudder power and a lot of rudder capability.”

Crew accommodations are some of the nicest in the fleet. Martin, the Bay Engineering president, said the ship is exceedingly quiet in the crew spaces, owing in part to additional fireproofing insulation that also dampens noise and vibration.

Fincantieri project manager Amelia Ott oversaw Mark W. Barker’s construction over almost three years that coincided with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing labor and supply chain challenges. “You name it, we experienced it,” she said with a wry smile.

Fincantieri project manager Amelia Ott oversaw Mark W. Barker’s construction over almost three years that coincided with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing labor and supply chain challenges. “You name it, we experienced it,” she said with a wry smile.

Prior to this ship, the last U.S.-built Great Lakes freighter left the yard before Ott was born. The same is true for many of the more than 500 workers that helped build the ship in Sturgeon Bay. “It was pretty cool to be part of this,” she said.

The same goes for Martin, who also highlighted the historical significance of Mark W. Barker. Given the age of the American laker fleet, he has spent a good chunk of his career working on conversion and modification projects rather than new construction. He’s watched as historic ship after historic ship was decommissioned. Mark W. Barker, on the other hand, represents ingenuity and innovation.

“I am hoping this is the beginning of an entire fleet renewal,” he said, referring to the broader U.S.-flagged Great Lakes fleet.

For now, that remains to be seen. But Interlake has high hopes for its new ship, which the company says cements its commitment to delivering important cargoes throughout the Great Lakes. “She truly was designed,” said Brendan O’Connor, Interlake’s vice president of marketing and marine traffic, “to be a ship for the future.” •