St. Rita had embarked on a short transit at a Lower Mississippi River fleeting area, one barge on its hip, when the vessels became caught in the fast-moving current and were pinned broadside against the fleet.

The 66-foot, 1,500-hp towboat heeled over and sank at mile marker 132 near LaPlace, La., at about 1430 on March 7, 2019. All five crewmembers escaped to barge LTD 14161 on St. Rita’s starboard side. A good Samaritan towboat rescued the crew. No one was injured, but property damage was estimated at $1.5 million.

St. Rita’s captain had more than two decades of experience operating towboats in rivers and canals, but little time working in fleeting areas. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) cited this lack of experience — particularly during high water, with a barge positioned on the towboat’s hip with a single headline — as the leading cause of the sinking.

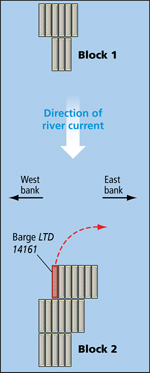

“The captain … started his transit across the head of the block where the current was strongest, rather than push farther up, closer to the upriver (barge) Block 1 where the current was not as strong, which would have given him more room to maneuver or to fall back in the current,” the NTSB said in its report.

Investigators praised St. Rita’s captain for sounding the general alarm at the first sign of trouble, a move they said probably saved lives.

St. Rita’s captain started work at 0300 and spent the day shifting barges at the Cooper Consolidated fleeting area in LaPlace, roughly 23 miles west of New Orleans. The Lower Mississippi was above flood stage, according to gauges upriver and downriver, and the current at LaPlace was moving at 5 to 6 knots.

St. Rita got an order at about 1300 to shift the empty hopper barge LTD 14161, which was about 200 feet long, from a barge group on the right descending bank to the left bank. It was the westernmost barge at the head of a barge group known as Block 2, located about 1,200 feet downriver from Block 1. Marquette Transportation, which operated St. Rita, has policies against “downstreaming” — a practice where towboats land against a barge with the current at their sterns. That meant St. Rita had to come alongside LTD 14161 to remove it from the barge fleet.

St. Rita’s two deck hands struggled to free the barge from the fleet, largely due to the current, although after about 15 minutes they were successful. They connected the towboat and barge via a single headline, with LTD 14161 positioned on St. Rita’s starboard hip. The vessels then began moving across the river toward the east bank to help build a tow.

St. Rita’s captain noticed the fleet boat Roger D. coming upriver along the right, or west, bank. Roger D. then turned toward the left bank, crossing between barge blocks 1 and 2. At some point it appeared to slow down, and St. Rita’s captain worried the vessel would “fall” downriver toward his position.

|

|

The location of barge LTD 14161 on the day of the accident and its approximate intended movement. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration |

The captain “turned St. Rita to starboard, and eventually the current grabbed the barge and he lost control of the tow. LTD 14161 collided with the barges moored at the head of Block 2 and became pinned (starboard-side to) against their bows,” the NTSB report said. “St. Rita’s starboard side was pushed against LTD 14161 by the current.”

The captain, who the NTSB did not identify, sounded the general alarm at about 1420 when he realized he had lost control. Two sleeping deck hands awoke, and the two on-duty deck hands helped them reach the wheelhouse. The worsening starboard list made it hard for the crewmembers to move around the vessel, but all five escaped to LTD 14161.

Rod C., a 2,000-hp fleet boat operated by Plimsoll Marine, responded to St. Rita’s distress call. The towboat’s crew then climbed onto Rod C. from LTD 14161. St. Rita sank at about 1430 when its headline connected to the barge parted.

St. Rita’s captain began working on the towboat in late 2018 when it was operating on a canal. At that time, the captain’s performance was evaluated by a Marquette port captain. The company did not check the mariner’s abilities to perform fleet work when it moved the towboat to the LaPlace fleet in January 2019. Instead, Marquette’s port captain took the captain’s word that he was “good to go” and comfortable handling fleet work.

The sinking spurred changes in Marquette fleet boat policy. According to the NTSB, the company restricted some operations during high water. Towboats were required to use multiple headlines when gathering a barge from a fleet, and they were required to “face up” to barges once they were freed from the fleet.

“The policy also required a towboat wheelsman to cross a tier of barges at the downriver end of the block,” the report said.

NTSB investigators homed in on the St. Rita captain’s interactions with his counterpart aboard Roger D. before the sinking. St. Rita’s captain spotted the vessel on the electronic charting system heading upriver along the right bank and assumed Roger D. would continue to travel upriver. The towboat’s turn to cross the river caught St. Rita’s captain by surprise.

“(He) was aware that Roger D. was nearby but chose not to call the towing vessel via VHF prior to getting underway with barge LTD 14161,” the report said. “His assumption that the other vessel would continue heading upriver would have been dispelled if he had called Roger D.”

A spokeswoman for Marquette, which is based in Paducah, Ky., did not respond to an inquiry about the NTSB findings.