The U.S. Coast Guard has begun to test automatic identification system (AIS) aids to navigation, including virtual buoys, on the West Coast as the first step toward introducing them around the country.

The pilot project, while promising many benefits to mariners, is raising some concerns about whether the training of pilots and watchstanders will be sufficient to handle the new technology. And there are questions about whether the system will be secure from hackers.

AIS is the internationally adopted radio communication system that allows autonomous and continuous exchange of navigation-safety messages between vessels, aircraft, shore stations and aids to navigation (ATON). AIS ATON stations broadcast their identity with a nine-digit Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) number, position and status at least every three minutes. Broadcasts can originate from an AIS station located on an existing physical aid (Real AIS ATON) or from another location (AIS Base Station).

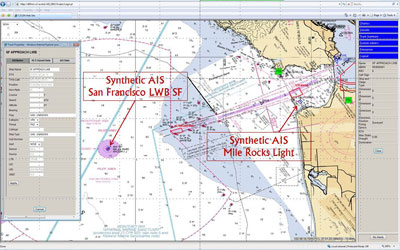

When an AIS Base Station signal is broadcast to coincide with an existing physical aid it is known as a Synthetic AIS ATON. When a signal is broadcast to a location in a waterway where there is no physical aid, it is known as a Virtual AIS ATON.

All three variations can be received by any existing AIS mobile device, but they require an external system such as AIS message 21-capable ECDIS, ECS, radar or a PC.

Lt. Dave Lewald, of the Coast Guard’s Visual Aids to Navigation branch in the Office of Navigation Systems, noted that AIS has been in use for more than a decade.

“It was initially started as a ship-to-ship collision-avoidance tool,” he said. “But the International Maritime Organization, recognizing that it had capabilities to serve as an aid to navigation, approved it for that use.” This summer, at its next meeting, IMO is expected to approve a set of symbologies.

“Parallel to all of this, the Coast Guard has been erecting what we call the nationwide AIS (NAIS),” Lewald said. The agency can program into the system the ability to transmit two types of AIS ATONs. With a synthetic, “we put that mark out there so when a pilot is coming in they will see the buoy, but on top of that they will have the AIS symbol. It seems kind of redundant, but what that does for us is it allows a quick comparison to make sure that that buoy is still on station. Particularly in a year like this when we had a lot of ice, that’s very important because the buoys kind of moved around quite a bit.”

The Coast Guard established several of these aids near San Francisco in February. The First Coast Guard District in the Northeast is preparing a list of buoys it wants AIS synthetics for as well, he said. And eventually it will be all over the country.

“The second type of AIS ATON that we’re using is literally a virtual in that we broadcast a signal out to an empty spot in the water so the only way you can see it is through your AIS in your radar or if you have an electronic charting system that speaks to your radar,” Lewald said.

The first full-functioning virtual aids were turned on March 12. “We’re using them to mark the call-in points for the San Francisco Traffic Separation Scheme,” he said. “So rather than putting an $85,000 buoy out there just to remind mariners to call in the VTS, we have the synthetics. The only mariners who are required to call in are SOLAS class, so they already have all of this equipment. So this is a phenomenally efficient use.”

“On the Western rivers, we have a real problem with bridges being hit by barge tows,” he said. “So we will be establishing virtuals marking the bridge piers.” Pilots and captains will be able to use the virtual markers to measure the distance between piers.

“What we’re doing is asking commercial users that have the capability to see these things — mostly pilots — and we want to start learning how to use them: what’s the best way to use this available tool that we have,” he said. Mariners with feedback should go to www.navcen.uscg.gov.

The length of the testing is open-ended, Lewald said. It will depend on the feedback from pilots, captains, chart manufacturers and other interested parties.

The feedback has already started.

Capt. Richard Madden, a maritime consultant who holds a Coast Guard unlimited master’s license and master of towing vessels license, said AIS “has proven to be a valuable and versatile method of transmitting information in a relatively small geographic area. While VHF range is normally line-of-sight, or in a best-case scenario 25 to 30 nm, it is not uncommon to see AIS signals picked up over a couple of hundred miles away.”

First seen overseas, he said AIS transmitters are finding their way into lighthouses, port control offices and most recently buoys.

Madden said Real AIS ATONs “is probably the best use of the AIS technology with buoys, as it marries the virtual position transmitted with the actual physical location of the buoy.”

He said a benefit of Synthetic AIS ATONs “might be decreased costs and maintenance, as potentially expensive and sensitive equipment wouldn’t be exposed to the elements. The drawback that jumps to mind is the possibility of the buoy being off station, which would not be reflected by the AIS signature, as the two are not physically connected.”

|

|

(Alan Haig-Brown) |

|

Virtual aids may be used to make bridge transits safer on Western rivers, such as the Snohomish River. |

As for Virtual AIS ATON, Madden said, “this aid would appear to have limited use, as it is dependent solely on the continued transmission of the signal, has no physical presence that can be viewed and is not viewable by all. Potential uses might be for marking newly found dangers, temporary security areas or other temporary markings.”

Madden and others say security is a concern as is an area’s capacity to handle multiple signals.

“How many AIS transmitters can be handled in a given area?” he asks. “We have already seen issues in the Persian Gulf where ECDIS units will ‘freeze’ due, we believe, to an overload of AIS signals. Before rolling out huge numbers of AIS-equipped buoys in an area such as New York or Long Island Sound, it should be ensured that the original function — vessel identification — is not adversely affected. As a mariner, I would much rather see small vessels such as sailboats equipped with Class B AIS units than see an AIS transmitter on each buoy.”

“Particularly with the synthetic and virtual ATON, the hackability of the network has to be tested before a large-scale rollout of the system,” Madden said. “The AIS system has already proven to be vulnerable to attack, with Trend Micro Inc. of Tokyo amply demonstrating the vulnerabilities.”

Robert Meurn, a retired professor from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and the author of the “Watchstanding Guide for the Merchant Officer” said, “I think AIS is great if it’s used properly. The big problem, just like when radar came, is that the people are not using them.”

He mentioned a collision in the North Sea in 2005 where “both ships had each other with AIS. Both masters were on the bridge. They had the name of the ship, the course and speed, their country, and they had each other visually on the radar and the AIS, and they didn’t even contact one another,” Meurn said. “The problem is not the equipment — the equipment works fine — it’s that the mariners are not familiar on how to use the equipment and using it to its full capability.”

He said it’s critical that captains and pilots get proper simulator training with the new technology.

“The key is education,” Meurn said. He said courses including use of AIS should be mandated by the Coast Guard and IMO.

Andrew McGovern, vice president of the United New York and New Jersey Sandy Hook Pilots Association and chairman of the Harbor Safety, Navigation and Operations Committee for New York Harbor, called synthetic AIS buoys “a good thing” and an improvement over unreliable racon buoys that return a Morse Code signal when hit by radar waves. “It would be more reliable and cheaper,” he added.

“The virtual AIS buoys have their pluses and minuses,” McGovern said. “If the boat sinks in a channel and the Coast Guard doesn’t have time to get out there and put a buoy marking the wreck, they could put a virtual buoy there so commercial vessels could see there is something there and avoid it.”

Like Madden, he said security against hacking “is one of the downsides.”

“There have been rumors that because buoys are expensive to maintain that the Coast Guard and other governments would like to go to just virtual buoys,” McGovern said.

Dr. Lee Alexander, of the University of New Hampshire’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, said the Coast Guard’s testing “is definitely needed. Any new development or ‘improvement’ in maritime navigation safety needs to be carefully evaluated before it is implemented.”

Alexander said the new technology could befuddle those on a bridge. “Referring to ATONs as ‘real,’ ‘virtual’ or ‘synthetic’ can be confusing,” he said. “Rather than call something a ‘virtual ATON,’ perhaps it would be better to refer to it as a ‘virtual’ navigation aid.”

He added that virtual ATONs raise several troubling issues. “While most AIS transceivers are capable of receiving AIS ATON broadcast messages, if the ECDIS (or ECS) does not receive (or cannot recognize) the ‘Virtual AIS ATON’ data being broadcast, how will the mariner know that it exists?” he asks.

Current approved ECDIS do not have a requirement to receive or portray AIS ATON information. Alexander said this may not change until after 2018 when the mandatory carriage implementation for SOLAS vessels is completed. “In the interim, will there be a requirement for mariners to have another external display for virtual ATONs?”

And, he said, “if a virtual ATON is only electronically charted and displayed (e.g., on radar, ECS or ECDIS), how will the mariner ‘identify’ it as being different than charted ATONs that physically exist — and are already shown on paper chart or electronic chart displays? Ideally, these are the kinds of issues that will be addressed during the USCG AIS ATON testing program.”

Lewald said he has heard the concerns.

“I’ve heard about the AIS spoofing,” he said. He added that while hacking is possible, the benefits far outweigh that risk.

As for the training issue, “right now the target audience is the commercial mariner,” Lewald said. He said he believes that “if this tool is made available, they will learn how to use it.” He expects training courses around the world to reflect the new technology.

As for the criticism that “this is just a ploy to remove physical ATON, that’s not the case. This is an enhancement,” he said.