California breathed a sigh of relief last fall when a survey of the wreck of Montebello, a World War II tanker torpedoed two weeks after Pearl Harbor, put to rest any fears of a catastrophic release of oil from the vessel, which sank in 880 feet of water with up to 3.2 million gallons on board.

But almost lost in the news coverage was a remarkable advance in undersea technology that could speed up and simplify the way high-priority wrecks are surveyed.

Seattle-based Global Diving & Salvage used equipment from the oil and gas industry called a neutron backscattering device to indicate whether there was oil in Montebello's tanks without boring holes in them.

|

|

Lowering the ROV over the side of Nanuq. The ROV is housed in a garage-like structure called the tether management system, or TMS. Mounting pingers on the TMS as well as the ROV gave the operators a better feel for where they were on the hull of the wreck. (Photo courtesy Global Diving & Salvage) |

Global incorporated this technology, developed by a company called Tracerco, into its own remotely operated vehicle (ROV), a Cougar-XT from Seaeye. Then the survey crew sat back and watched as data from the wreck poured into the operations center aboard Nanuq, a chartered 301-foot spill response vessel built in 2007 by Edison Chouest Offshore.

"This was one of the first big tests of that technology," said David DeVilbiss, manager of Global's maritime casualties division and the project manager for Montebello.

"Essentially you have a radiation source contained in a special housing. It has the ability to direct the particles into the hull, and a device measures the neutrons bouncing back from whatever is inside. If they know the thickness of the steel and the components of the steel, they can subtract that from the total reading and the balance will give them an indication of what's in there."

The device is calibrated so that its operators know whether any given reading indicates water or oil. The results were pretty clear. "We got mostly water readings throughout," said DeVilbiss.

|

|

Montebello in Vancouver, Canada, in 1926. (Photo courtesy Vancouver Maritime Museum ) |

Lisa C. Symons, resource protection coordinator for the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said Montebello has important lessons for tackling wrecks that pose the threat of pollution.

"The new technology — allows us to do the assessments much more quickly and in a much less invasive way," said Symons. "We can have an assessment of the Montebello done in 10 days instead of probably double or triple that."

In addition, minimizing time on scene cuts costs. "That's where the big money starts to pile on," said DeVilbiss.

Symons said the last wreck recovery effort off the California coast, Jacob Luckenbach, cost about $22 million. Montebello, which did not require oil recovery, was budgeted at about $5 million.

Out at the wreck site, the survey crew pulled samples from the cargo tanks, which verified the absence of oil.

"We drilled in through the side of the vessel, pulled a 100-milliliter sample (a little more than 3 ounces) of the internal contents and turned that over to the Coast Guard," said DeVilbiss.

|

|

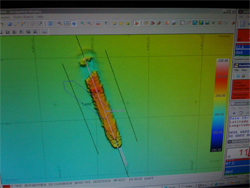

A sonar reading of Montebello on the ocean floor. The colors indicate depth, so red is the high point on the superstructure. The torpedo struck the bow of the vessel, which is shown lying separated from the rest of the ship. (Photo courtesy Global Diving & Salvage) |

To do this, the company developed an in-house tool that it was using for the first time. "It pulls the sample, and then, as the tool is retracting, it seals it up," he said.

The final task was to take what are known as "coupons" out of the hull — six steel disks that will help scientists understand how wrecks are affected by corrosion and marine growth. The data turned over with these includes temperature, salinity and oxygen saturation.

DeVilbiss said Global held to its original schedule on the survey, which was timed to beat the onset of the North Pacific winter. But the venture did have its surprises.

|

|

Sites of the U.S. wrecks identified by NOAA as posing the greatest risks to the environment. (Photo courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) |

The team had to use remotely operated barnacle busters to clean patches on the hull because "there was a lot more marine growth than we'd been expecting," DeVilbiss said.

"It didn't set the operation back too much, except occasionally you'd have crabs come and sit on top of the gauges you were trying to watch."

Until the survey cleared it as a pollution threat, Montebello was one of several high-priority wrecks identified by NOAA from a database called RUST (Resources and UnderSea Threats), which the agency started developing in 2003 after Luckenbach (See story, PM #118).

As information was developed, the criteria were refined to pinpoint tankers and tank barges built after 1891 and greater than 200 feet or 1,000 gross tons. Almost all are steel-hulled.

"We're currently sitting at about 211 vessels, of which about 25 are on our high-priority list," said Symons. Ten ships are reported to be leaking, she said, but not all are top priority — a couple are simply "burping slightly."

Meanwhile, it's unlikely anyone will ever determine what happened to the oil from Montebello. None was reported on beaches after the sinking, and reports from the crew — all 38 survived — did not indicate a catastrophic release at the time of the attack. "It truly is a mystery," Symons said.