In early May, the U.S. Interior Department’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) announced in Port Fourchon, La., that drilling measures implemented after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill would be eased. The Obama administration enacted the offshore regulations, together known as the Well Control Rule, in July 2016.

The revisions follow complaints that the 2016 standards were “one size fits all” and not flexible enough. In May of last year, BSEE proposed revising the Well Control Rule in the Federal Register and received 118,000 responses. The Interior Department’s new final rule on well control and blowout preventers, or BOPs, became effective this July 15.

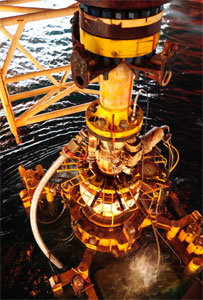

According to the Interior Department, the new rule corrects errors from 2016 and reduces burdens on oil operators. Drillers can test components of their BOP safety devices less frequently, saving them money. And operators are no longer required to use BSEE-approved verification organizations to certify BOPs.

The new regulations change 68 of the 342 well control provisions from 2016 and add 33 requirements, including new limits on the number of connection points to BOPs.

In May, the American Petroleum Institute said the changes give offshore operators flexibility to innovate and develop technologies, while also improving safety. Reforms to the rule, the API said, support steps by industry and the BSEE to prevent and respond to a spill; revise flawed technical requirements; set a performance-based standard so that safe drilling margins can be established case by case with well data; and allow decision-making by on-site well personnel subject to the BSEE’s authority.

Barry Russell, president and CEO of the Independent Petroleum Association of America, said in June that while the BSEE’s revised rule “remains largely unchanged, targeted changes in their rewrite allow producers to be nimbler.” He added that “more adaptive guidelines, based on the most up-to-date insights and innovative technologies in offshore exploration and development, will improve safety and certainty in the regulatory process.”

“IPAA supports BSEE’s efforts to modernize regulations for an ever-improving offshore industry that places protection of its workers, the environment and coastal communities first,” Russell said.

The BSEE will be responsible for seeing that the new regime is followed. “As the federal agency charged with regulation and oversight of energy operations on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf, our agency will perform all reviews and inspections necessary to enforce the rule,” said Karla Marshall, the BSEE’s Gulf of Mexico spokeswoman.

Under the 2016 rule, drillers were given some leeway. “Alternate compliance approvals” were granted for procedures and equipment when operators could show that their proposals provided safety and environmental protection that met or exceeded BSEE requirements, Marshall said. From Aug. 1, 2016, to Jan. 19, 2017, during the Obama administration, 692 alternate compliance approvals were granted. During the Trump administration, 960 alternate approvals were granted to operators from Jan. 20, 2017, to March 22, 2018, she said, without providing any data for the period beyond that date.

Meanwhile, the Gulf is still feeling the effects from the 2010 spill. In a letter to BSEE Director Scott Angelle on Aug. 6 of last year, the Virginia-based Southern Environmental Law Center stated that the only analysis the BSEE seems to have done to justify changing the 2016 rule was to project $986 million in savings to industry, along with a $100 million indirect boost to the economy, both over 10 years. Those amounts are just drops in the bucket compared to the billions of dollars in damage that can be caused by a spill, the center said.

On June 11, 10 environmental groups opposed to the rule changes filed a lawsuit in federal district court in San Francisco. Earthjustice, the Southern Environmental Law Center and others said that lowering standards for critical safety components, equipment inspections and well monitoring will allow self-regulation similar to the system that prevailed when the Deepwater Horizon disaster occurred.

A poorly maintained BOP led to the rig explosion that killed 11 offshore workers and injured 17 others in April 2010. As 200 million gallons of oil spewed into the Gulf over 87 days, a massive response by the Coast Guard and other assets was needed to stop the spill. Since then, rig lessee BP has paid out $70 billion in compensation, fines and cleanup costs.