The Costa Concordia disaster has focused scrutiny on the cruise industry's longstanding willingness to sail vessels into potentially hazardous waters merely for entertainment purposes.

|

|

The grounded cruise ship lies on its side off the island of Giglio, Italy, on Feb. 1. The 952-foot cruise ship with over 4,000 people aboard is said to have deliberately navigated close to the island to perform a 'salute' to the island's residents. (Associated Press photo) |

Captains should be very cautious when doing this, according to maritime safety consultants and lawyers. Don't get cocky or complacent, be sure to maintain situational awareness and consider whether it's best simply to say no.

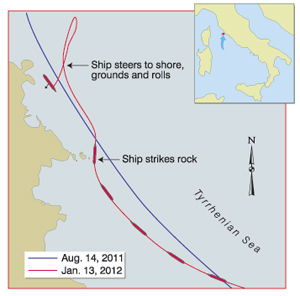

As many as 32 people were killed Jan. 13 when Costa Concordia partially sank and rolled over onto its side after striking a rock while sailing close to the western Italian island of Giglio. There was no navigational reason to be anywhere near the rocks. The 952-foot cruise ship deliberately steered alongside the island to perform a salute, or "take a bow," to the inhabitants, officials said.

The incident is an extreme example of what can happen when a captain attempts a dangerous maneuver to please guests or spectators. Many kinds of passenger vessels have experienced casualties or close calls when they strayed into hazardous water for reasons other than navigational necessity.

Alaska and polar cruise ships steer alongside glaciers or shorelines to give passengers a closer vantage point. Whale-watching boats want to get as close to whales as possible. Some coastal dive tour boats try to give their guests a close look at caves.

"That's more common than people think," said Clark Dodge, a Hawaii-based passenger vessel safety consultant. "On a cruise ship, they have a much wider window to entertain the guests. They have to be at a certain port on a certain day, but they also want to please the passengers and they — I won't say break the rules — but they have discretion."

Cruising open water can become monotonous. There can be a great temptation to move in closer to interesting scenery, and shipowners may officially or unofficially encourage it.

|

|

After striking a rock off Giglio on Jan. 13, the ship slowed almost to a halt, reversed direction and then went aground. Five months earlier, the ship had also passed close to the island but without incident. (Virginia Howe illustration/Source: Quality Positioning Services BV) |

"You have promised people the sights of a lifetime. Sometimes you have to be opportunistic about it. Maybe a glacier is coming or there are bears ripping apart salmon on the shore," said Capt. Daniel Parrott, associate professor of marine transportation at Maine Maritime Academy. "What you can't lose sight of, first and foremost, is the safety of the vessel and everybody on it."

Shipmasters must not allow employers or guests to cajole them into risky behavior, Parrott said. Neither should captains allow their judgment to become clouded by ego or complacency.

"It may be that the company, with a wink and a nod or some implicit way, is saying this is something they would look favorably on to give passengers a pleasant experience, but you cannot take your eye off the fact that you are the person on the scene and you are responsible," Parrott said.

Masters pondering a trip into marginal waters must consider weather conditions and sea state. They also need to think about what would happen if a system failure or other problem occurs.

"When you go into a shallow area or an area where there are hazards, you decrease your margin for error," said Wayne Meehan, a maritime casualties attorney in New York. "If you have an engine breakdown, you have a problem. It's that much more critical to maintain a proper watch and maintain situational awareness."

The owner relies on the captain to make such decisions based on observations and judgments on site, and Dodge said the captain can't delegate that assessment to the mate or other crew.

"To take a ship into an area that's shallow or there's any possibility of rocks, there's one person responsible, and that's the captain," Dodge said. "If they screw up and there's a current, they're going to run aground or hit something."

In the United States captains risk not only civil liability but also criminal charges. If a death occurs and negligence is alleged, the captain can be charged under the Seaman's Manslaughter Statute. A criminal case also could result if oil spills.

Unnecessarily sailing into a risky area would increase the likelihood that a prosecutor would assess the conduct to be unreasonable and pursue criminal charges, said Meehan, a former chief mate on oceangoing ships.

"If you go into an area that you didn't have to go in or you didn't need to go that close — if you went 200 yards away from a rock — someone's going to say that's negligence," Meehan said. "If you went a half-mile away from the rock, it's not."

While the onus is now on captains, the Costa Concordia incident may inspire regulators to place more responsibility on the operating company to monitor voyage plans. Hundreds of millions of dollars in lawsuits and insurance claims are likely to arise from the accident. Industrywide, stakeholders may push for "black-box technology" to increase "the connectivity between management ashore and the vessel afloat," said Clay Maitland, managing director of International Registries Inc.

"The ship went where it shouldn't have been. The claim will be made that the ship wouldn't have been there if the management ashore had monitored it better," he said. "We may have the declining independence of the ship's master and mates."

Not all operationally unnecessary maneuvers involve shallow waters or rocky coastlines. Another example is tall sailing ships in a regatta. The tall ships are closely grouped, and they have a tendency to unfurl all their sails while putting on a show for the spectators, even if the configuration isn't ideal for conditions.

"The shores of the harbor may be lined with thousands of people," Parrott said. "Nobody's telling you to carry all sail, but you know you are there to create a spectacle — without losing sight of the safety part."

Whether it's a sailboat, whale-watching boat or cruise ship, operators will want to delight the public.

"Still, the captain is the captain," Parrott said. "You can't lose sight of the overriding responsibility. You have to make the call to go conservative. You have to build in a margin of safety. Yes, you want the passengers to go home happy, but they're not going to go home happy if the ship sinks."