The overtaking situation is generally regarded as a type of vessel encounter presenting the least risk to the vessels involved. This is primarily due to the fact that, in contrast to crossing and head-on situations, overtaking often involves low relative speeds between the vessels, resulting in a more slowly developing situation that the mariner is better able to appreciate, analyze and react to.

|

|

In this starboard quarter approach, the relative position of the vessels and configuration of navigation lights change over time. While the steering and sailing rules apply to vessels in sight, this scenario can still lead to confusion as to whether this is an overtaking or crossing situation under certain circumstances. Never assume the other vessel shares your view of which rules apply. Be prepared to take evasive action. |

Despite this perception of low risk, mariners must be aware that there are certain risks inherent to overtaking. Overtaking situations frequently require vessels to be in close proximity to each other for extended periods of time, resulting in an increased danger of collision between vessels if there is a failure to appreciate a change in course or speed of one of the vessels, as well as potentially limiting both vessels’ maneuverability, which may be required as other crossing or head-on traffic is encountered. Furthermore, the starboard quarter approach, one of the most nuanced aspects of the overtaking situation, presents a very real risk to both vessels when there is a lack of appreciation of the situation or a misapplication of the rules, which can lead to confusion as to the status and responsibilities of vessels.

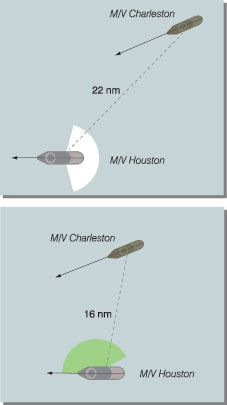

Consider the following hypothetical scenario. It is a calm, clear night in the western approaches to the English Channel. Charleston, a 950-foot containership, is outbound on a west-southwesterly course making 20 knots. Houston, a 550-foot petroleum product carrier, is outbound on a westerly course making 12 knots. Houston is 22 nm southwest of Charleston when Charleston first begins to track it on radar, but Charleston has not seen it visually at that time. The situation continues to develop and Houston is 16 nm southwest of Charleston when Charleston is able to make out its green sidelight and white masthead lights. By the time the vessels are eight miles from each other, neither vessel has altered course or speed and there is a zero-nm closest point of approach.

At this point, the vessels converse on VHF radio and it becomes apparent that there is a disagreement between them as to the status of Charleston. Houston believes that Charleston started out as an overtaking vessel, that a subsequent change in bearing between the two vessels cannot make it a crossing vessel, that Charleston is the give-way vessel and that Charleston should alter course or speed to keep out of the way of Houston. Charleston believes that Houston, although stating the applicable rule correctly, has misapplied the rule to the situation and its analysis is flawed. Charleston has no doubt that this is a crossing situation, that Houston is the give-way vessel and that Houston should alter course or speed to keep out of the way of Charleston. How should this encounter, which one vessel sees as an overtaking situation and the other vessel sees as a crossing situation, be resolved?

ColRegs Rule 15 governs crossing situations and states that, “when two power-driven vessels are crossing so as to involve risk of collision, the vessel which has the other on her own starboard side shall keep out of the way and shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, avoid crossing ahead of the other vessel.”

ColRegs Rule 13 governs overtaking situations and states that, “any vessel overtaking any other shall keep out of the way of the vessel being overtaken.” This rule applies to all vessels, not just power-driven vessels, as is the case in crossing and head-on situations. The rule does not require the overtaking vessel to maneuver in any particular manner, generally allowing an overtaking vessel to pass on either side of the overtaken vessel. However, care should be exercised by the overtaking vessel to maintain an appropriate distance off the overtaken vessel to prevent the effects of interaction, as well as to ensure that it is well clear of the overtaken vessel before any subsequent alteration of course ahead of the overtaken vessel.

Rule 13(b) states that, “a vessel shall be deemed to be overtaking when coming up with another vessel from a direction more than 22.5 degrees abaft her beam,” such that only that overtaken vessel’s stern light and neither of its sidelights would be visible at night. Thus, there are clear tests that can be employed, which are intended to eliminate any doubt as to whether a vessel is overtaking or crossing. A vessel may employ the use of radar and automatic radar plotting aids to determine its relative position and angle of approach, as well as observe the lights of other vessels. Despite these efforts at providing a bright line test for determining one’s status, there are certain factors, such as the failure to track a vessel on radar or the range at which lights may become visible and identified, which may lead to uncertainty. However, Rule 13(c) attempts to resolve any uncertainty as to the status of an overtaking vessel by stating that, “when a vessel is in any doubt as to whether she is overtaking another, she shall assume that this is the case and act accordingly.”

Finally, Rule 13(d) states that, “any subsequent alteration of the bearing between the two vessels shall not make the overtaking vessel a crossing vessel within the meaning of these Rules or relieve her of the duty of keeping clear of the overtaken vessel until she is finally past and clear.” Rule 13(d) is intended to resolve the starboard quarter approach problem. Whereas a vessel coming up on another vessel’s port quarter would be the give-way vessel regardless of whether it is an overtaking or crossing situation, the same cannot be said for the starboard quarter approach, where the vessel coming up would be the give-way vessel in an overtaking situation and the stand-on vessel in a crossing situation. Rule 13(d) is intended to prevent such a shift in status by prohibiting an overtaking vessel, by virtue of a change in its position relative to the overtaken vessel, from becoming a crossing vessel once it is less than 22.5 degrees abaft of its beam or in such a position as to see its running light and masthead light(s) and not its stern light.

Despite the bright line tests for overtaking status, default assumption of overtaking status, and prohibition on shift in status from overtaking to crossing set forth in Rule 13, the starboard quarter approach nevertheless presents problems in application. Mariners who are competent in their knowledge of the ColRegs are still subject to misapplication of the rules resulting from faulty appreciation or analysis of the situation. Consider the previously mentioned hypothetical scenario involving Charleston and Houston wherein the vessels disagreed about the status of Charleston as either an overtaking or crossing vessel. The key to analyzing this scenario is the relative position and angle of approach of Charleston at the time Charleston was able to make out Houston’s green sidelight and masthead lights.

Rule 13 governing the overtaking situation and Rule 15 governing the crossing situation are part of the steering and sailing rules and, as such, Rule 11 states that these rules “apply to vessels in sight of one another.” Rule 3(k) states that, “vessels shall be deemed to be in sight of one another only when one can be observed visually from the other.” The implications of this definition are significant, as only visual observations made by the mariner’s eye, as aided by binoculars or other optical aids, meet the requirement of being in sight. As Craig H. Allen, University of Washington law professor, retired U.S. Coast Guard officer, and recognized authority on the ColRegs, notes rather tongue-in-cheek in the eighth edition of Farwell’s Rules of the Nautical Road, “there are those who would argue that even observations using these optical devices should be excluded. Whether these hair splitters would exclude eyeglasses as well is unclear.” Regardless, it is clear that for vessels to be in sight of one another, there must be a visual observation by the mariner and not merely an electronic observation, e.g. tracking by radar.

In the aforementioned scenario, while Charleston was initially more than 22.5 degrees abaft of Houston’s beam when it began tracking Houston on radar, Charleston was less than 22.5 degrees abaft of Houston’s beam when it was able to make out Houston’s lights. As a result of its relative position and angle of approach at the time the two vessels were in sight, Charleston was not locked in as an overtaking vessel, but rather enjoyed the status of a crossing vessel to starboard. Accordingly, Houston should take early and substantial action by altering course or speed in order to keep out of the way and well clear of Charleston and, if the circumstances of the case admit, avoid crossing ahead of Charleston.

However, there is room for confusion in the starboard quarter approach where factors such as differences in vessels’ height of eye and visibility of lights can lead vessels to reach different conclusions about the rights and responsibilities of vessels involved in the encounter. It is entirely possible that Houston would maintain the validity of its analysis and insist that it is the stand-on vessel in an overtaking situation. In that event, even if Houston had incorrectly analyzed the situation, Charleston would be permitted and eventually required to take action under the rules even as the stand-on vessel in a crossing situation. Rule 17 would allow Charleston to take action to avoid collision by its maneuver alone when it became apparent that Houston was not taking appropriate action and would require Charleston to take action to avoid collision when it became apparent that collision could not be avoided by the action of Houston alone.

While a seasoned deck officer may not consider the starboard quarter to be one of the most esoteric aspects of the ColRegs, it is a fine example of the importance of not only knowing the ColRegs, but also the importance of analyzing situations accurately and applying the ColRegs correctly. As this scenario demonstrates, a lack of appreciation of the situation or a misapplication of the rules can lead to confusion as to the status and responsibilities of vessels. Mariners involved in a starboard quarter approach situation should never assume that the vessel ahead/to port considers itself to be the give-way vessel in a crossing situation or, likewise, that the vessel astern/to starboard considers itself to be the give-way vessel in an overtaking situation and should be prepared to take avoiding action as necessary in accordance with the rules.

—————-

Samuel R. Clawson Jr. is an attorney with Clawson & Staubes LLC in Charleston, S.C., who holds an unlimited tonnage merchant marine deck officer’s license and has sailed for a major international container liner. He has lectured on topics including terrestrial navigation and Rules of the Road.