Improper lookout and a crewman’s lack of fluency with the autopilot system were leading factors in an allision last year in the Gulf of Mexico that ignited an unmanned drilling platform, according to federal investigators.

Connor Bordelon, a 257-foot offshore supply vessel, was traveling back to Port Fourchon, La., from the deepwater oil fields when it struck the platform South Timbalier 271A at 0432 on Jan. 23, 2015. The incident occurred roughly five nautical miles from the port’s entrance jetties.

The allision tore a hole in Connor Bordelon’s hull and ruptured oil and gas pipelines connected to the platform, causing them to catch fire. Good Samaritan vessels operating nearby quickly extinguished the flames.

“The probable cause of the allision of the offshore supply vessel Connor Bordelon with the unmanned natural gas platform South Timbalier 271A was the failure of the mate on watch to ensure that the bridge team maintained a proper lookout, and his delay in changing from the autopilot to manual steering,” according to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) incident report.

The delay in disengaging the autopilot “precluded him from taking the necessary action to prevent the allision with the platform,” the report said.

Bordelon Marine of Lockport, La., owns and operates Connor Bordelon, which was built in 2013. The company did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the NTSB findings.

In the days leading up to the allision, Connor Bordelon was working alongside the deepwater drillship Discoverer Inspiration roughly 110 miles offshore. There were 24 people on board: 14 crewmembers and 10 employees of Baker Hughes involved in fracking operations. The OSV began the roughly 12-hour trip back to Port Fourchon at about 1800 on Jan. 22, 2015.

The bridge team at the time of the incident consisted of two mates, an able seaman and an ordinary seaman, with the captain and another mate having recently completed the noon-to-midnight watch, the report said. At 0340 on Jan. 23, the mate on watch took the controls while the mate he relieved rested on a small couch in the wheelhouse. The AB was in the galley and the OS was in the captain’s office, which offers poor forward visibility. Nobody was designated as the lookout.

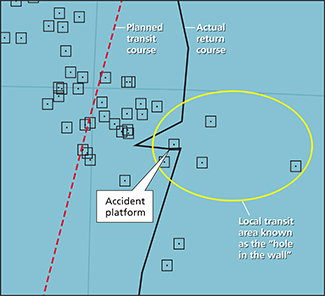

The mate at the controls told investigators he was using the autopilot system and adjusted the course to account for wind. Weather at the time was cloudy with passing rain showers, visibility of three to five miles and winds up to 20 knots. Seas reached 5 feet. The vessel was making about 8 knots as it approached the “hole in the wall,” an area of open water between charted obstructions.

Bridge video cameras recorded the first signs of trouble at 0428 when the platform was about a half-mile away. The mate noticed a flashing light in the distance and then left the captain’s chair for 28 seconds. At 0430, he left again to fetch binoculars in the aft bridge without notifying anyone he was leaving the forward bridge, the report said.

|

|

The map above shows drilling platforms in the area and the OSV's approach line. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/Sources: NTSB, U.S. Coast Guard |

About 90 seconds later, video shows the mate gesturing out the window. He also appears to have summoned the other mate and the OS. As they looked out the window, the mate at the controls directed his attention to the ship’s autopilot. They were about 30 seconds from impact.

“The mate at the conn stated that he was able to reduce the engine rpm but was not able to disengage the autopilot fast enough to maneuver away from the platform,” the report said. “At 0432:00, the video showed the crew on the bridge bracing for an impact and some articles falling off shelves, indicating the point at which the vessel allided with the unmanned platform.”

The mate later told investigators he did not see the platform on radar and thought it might have been “obscured by clutter depicting the rain in the area.”

The vessel struck the platform on the port bow above and below the waterline. The captain awoke upon impact. He returned to the bridge within a minute and notified the Coast Guard of the accident. The crew determined the ship sustained hull fractures below the waterline and was taking on water. Coast Guard officials let the vessel return to shore.

The 60-year-old mate at the controls had about a year of experience on the 2-year-old ship. He described himself as “old school” and admitted struggling with the ship’s modern technology and equipment, the report said. Authorities later determined the ship’s console had an emergency button just below the autopilot touch screen that would have immediately restored manual control. The mate told investigators he did not know the button was there.

Investigators identified problems with the ship’s voyage plan and also learned several key crewmembers were not certified with the ship’s electronic chart display and information system, or ECDIS. The captain told investigators the vessel was to plot a course toward the area of rig congestion and then steer around it using visual sightings and radar. Federal investigators also determined the ship’s course line was not consistent with trying to steer through the “hole in the wall.”

“If the course line had been drawn through the ‘hole in the wall’ and the vessel had been navigated along this intended track, the vessel would have had greater separation from the charted platforms,” the report said. “Instead, the mate on watch picked a point ahead of the vessel and steered toward an opening between the rigs, where less separation existed.”

Although NTSB officials acknowledged it was challenging to chart a course in portions of the Gulf to avoid all obstructions, “failing to plot and follow a trackline that is clear of most charted obstructions is an inherently poor practice for marine operations.”

The crew’s failure to check the route for obstructions and maintain a proper watch violated Bordelon Marine’s own internal safe operations manual, the NTSB said.

The accident caused up to $500,000 in damage to Connor Bordelon and $4.1 million in damage to the platform.