|

|

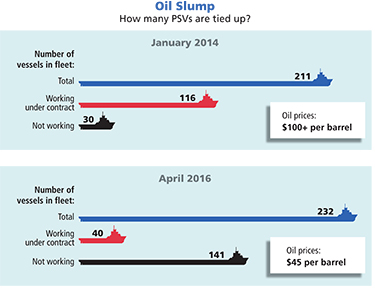

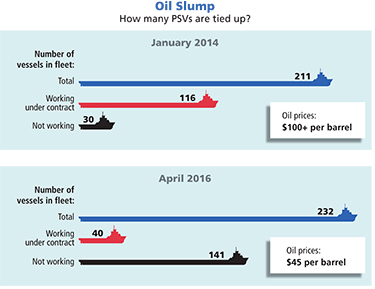

The number of platform supply vessels in the Gulf of Mexico that are not working has more than quadrupled since the crude price rally reached its peak in early 2014. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/Source: IHS Petrodata |

Vessels cold-stacked. Hundreds of mariners out of work. And crude prices nowhere near the $107-per-barrel peak that kept companies working — and investing — in the Gulf of Mexico’s shallow waters just two years ago.

For people like Glen Ghirardi of Morgan City, La., it’s a painful reality that has him wondering aloud if oil and gas exploration on the shelf will ever come back.

“What I see happening is we’re kind of being left behind like the coal industry,” said Ghirardi, owner of Ghirardi Marine Agency, a placement service for mariners. “It’s tough to stay positive when you’re the warehouse for jobs and you look on your shelf and there’s nothing there. It’s my faith in the Lord that keeps me going.”

Ghirardi said many of the companies he works with have cold-stacked their boats. “Taken the insurance off them and everything,” he said. “People can’t work for nothing (and) there’s a lot of people out of work down here. A lot of people.”

Richard Sanchez is IHS Petrodata’s lead marine analyst for the Americas, and what he sees isn’t rosy, either. He cites these numbers:

• In January 2014, when oil hit its peak of $107 per barrel, the number of platform supply vessels (PSVs) from 1,000 deadweight tons (dwt) to 2,999 dwt in the Gulf was 211. Of those, 116 (55 percent) were working term — contracts greater than 30 days. Only 30 vessels (14.2 percent) weren’t working at all.

• As of April 2016, with oil hovering around $45 per barrel, only 40 of 232 vessels were working term (17.2 percent) and a whopping 141 were not working at all (60.8 percent).

With a crew of seven or eight on each vessel, Sanchez’s numbers suggest that up to 1,100 mariners are out of work, and his count doesn’t include crew boats, utility vessels or PSVs less than 165 feet long.

“The forecast looks incredibly pessimistic,” Sanchez said. “Even with really strong oil prices, I just don’t see a return to shallow water. It has historically been played out.”

As evidence, he pointed to the decline in working jackup rigs in the Gulf. He said there were 25 to 35 when oil prices were at their peak. In the last year and a half, he said, the number of contracted jackups in the Gulf has dropped to five.

“What’s remaining on the (shallow) shelf is gas,” Sanchez said. “We’d need natural gas prices to improve to stimulate drilling on the shelf. But I don’t see a dramatic return to 2010-2014 levels. When we had $100 oil, it made drilling and producing oil profitable. And that kept the jackup market working.”

The downturn has some big maritime companies repositioning themselves.

In March, publicly traded Tidewater Inc. announced it had borrowed $600 million under its revolving credit facility — the maximum amount available — to enhance the company’s liquidity position and financial flexibility.

“Like the entire energy services industry, Tidewater continues to face challenges arising from the decline in the level of offshore oil and gas drilling and development activity around the world,” Jeff Platt, president and chief executive of Tidewater, told shareholders.

Another barometer of the downturn is Port Fourchon, Louisiana’s southernmost port that services 90 percent of oil and gas operations in the Gulf. According to Leigh Guidry, port affairs coordinator, there are about 400 vessels in the port every day.

“Sometimes they’re moving, sometimes they’re not,” she said. “We’re still busy. We have a generally depressed market, but we have not seen a great deal of packing up and moving out.”

For the most part, Ghirardi concurs. He said from his experience about 75 to 80 percent of the mariners working the Gulf are local residents — “Gulf people,” he said. The others are from out of town, and they likely have left the area.

“I don’t think they’re (local mariners) leaving the business,” he said. “They’re trying to manage until they can figure out what the heck is going on.

“The general opinion is that everybody’s looking for (2017). It won’t be an overnight thing, but it’s gradually picking up. I think before you see a turnaround, it will have to get to $60 or $70 a barrel.”

In the meantime, what few jobs Ghirardi has to offer are largely going to overqualified mariners.

“I’m actually putting captains to work making deck hand pay just to keep them working,” he said. “But there’s just a lot of them sitting at home collecting unemployment or trying to figure out what’s next.”