Deck crew aboard USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) mistakenly believed the destroyer lost its steering before a collision near Singapore in 2017 that left 10 American sailors dead and 48 injured, according to U.S. investigators.

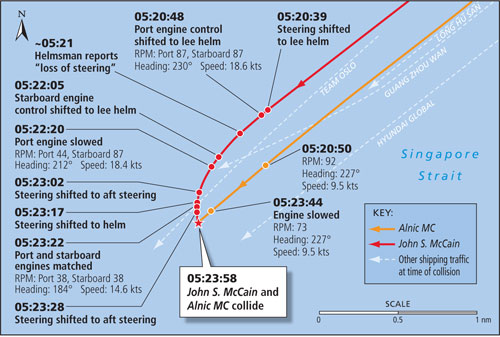

In reality, a crewmember aboard McCain tasked with transferring thrust controls inadvertently transferred steering controls to an adjacent control station. The ship veered to port into the path of the chemical tanker Alnic MC while crew tried to resolve the issue.

The collision occurred Aug. 21, 2017, at 0524 in the Singapore Strait about five miles from Horsburgh Lighthouse. The destroyer required $100 million in repairs, while the tanker sustained $225,000 in damage. No injuries were reported among the 24 crew on the tanker.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators identified myriad issues aboard McCain, including the decision to transfer thrust controls while in such a busy waterway, and the failure to notify nearby vessels by VHF radio of the ship’s loss of control. Crew fatigue was another concern.

In conclusion, the NTSB attributed the collision to “lack of effective operational oversight of the destroyer by the U.S. Navy, which resulted in insufficient training and inadequate bridge operating procedures.”

“Contributing to the accident were the John S. McCain bridge team’s loss of situation awareness and failure to follow loss of steering emergency procedures, which included the requirement to inform nearby traffic of their perceived loss of steering,” the NTSB said in a 47-page report released in early August. Investigators added that the ship was operating in a mode that “allowed for an unintentional, unilateral transfer of steering control.”

The incident effectively ended the Navy career of John S. McCain’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Alfredo Sanchez, who in May 2018 pleaded guilty to negligence. In August 2019, officials announced that the Navy will replace touch-screen control systems on its destroyers with mechanical controls starting in summer 2020.

|

|

NTSB/Pat Rossi illustration |

“The design of the John S. McCain’s touch-screen steering and thrust control system increased the likelihood of the operator errors that led to the collision,” the NTSB said.

The Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, based in Japan, was sailing southwest at 18 knots on the morning of the incident en route to the Port of Singapore. Alnic MC also was heading southwest, but at a slower speed. Sanchez requested that two crewmembers helm the vessel, with one focused on throttle and the other on steering, to prevent one person from being overwhelmed in the very busy waterway.

Sanchez made that decision as the main helmsman was about to eat breakfast. Instead, this helmsman was asked to take the throttle controls in the lee control station next to the main helm station. A second watch stander sat next to him at the helm controls. Crew transferred the port throttle control to the lee helm station without issue at about 0520. The starboard throttle control remained at the helm station. Moments later, the perceived steering issue arose.

“Although the crew had intended to transfer control of only the propellers to the lee helm, video footage … showed that, at 05:20:39, the mode of steering changed from backup manual to computer-assisted manual, and control of steering changed from the helm to the lee helm station,” the report said.

McCain began turning to port as its rudders moved from 3 degrees starboard to 0 degrees. The turn accelerated after crew ordered the speed reduced to 10 knots. The port engine slowed to 44 rpm, but the starboard engine remained at 87 rpm.

Steering control bounced back and forth between the wheelhouse and aft controls over 26 seconds starting at 0523. While in aft control, the rudder was briefly moved hard to port, further accelerating the ship’s turn toward Alnic MC. McCain’s wheelhouse crew got control of the steering system and moved the rudders to starboard less than a minute before the collision, but by then it was too late.

A large red override button on the bridge control system that would have restored steering controls to the main helm station was never pressed. Crew did not fully understand how it worked, instead believing it sent steering controls to an aft station.

|

|

USS John S. McCain is loaded onto the heavy-lift ship M/V Treasure on Oct. 11, 2017, to be taken to Navy fleet facilities in Yokosuka, Japan, for repairs. |

|

U.S. Navy photo |

The master aboard Alnic MC noticed McCain turning in the tanker’s direction but initially believed the destroyer would pass in front of his ship. He reduced speed to half ahead when a collision appeared likely, and the tanker struck the warship bow-first at about 9.5 knots. The vessels never communicated via radio before the collision.

“When the vessels collided, the Alnic MC’s bulbous bow opened a 28-foot-diameter hole in the John S. McCain’s hull, above and below the waterline, resulting in significant structural and flooding damage to several spaces, including crew berthing,” the NTSB report said.

Investigators learned fatigue likely affected many key personnel on McCain’s bridge. The lee helmsman reported he did not sleep the night before the collision, while the conning officer had three hours of sleep. Several other officers on deck had about four hours of sleep, while the commanding officer and executive officer had five hours and four hours of sleep, respectively, that they both described as “poor.” The average sleep for the 14 crew in the wheelhouse was 4.9 hours in the previous 24 hours.

Shifting watch schedules likely contributed to fatigue. “Following the accident, the Navy mandated ‘circadian watchbill’ schedules that followed set watch times each day,” the report said.

Since the incident, the Navy has undergone comprehensive training, maintenance and certification reviews, and a crew readiness assessment for ships like McCain based in Japan. The service also has emphasized maritime skills and seamanship training for surface warfare officers.

The NTSB recommended highlighting the importance of VHF radio use for Navy crews and aligning Navy sleep standards with international protocols. It also suggested additional training for helmsmen.

A Navy spokesman requested questions about the NTSB findings via email but did not respond to them by press time.