More than a century has passed since RMS Titanic was lost in the North Atlantic, a tragedy that led to the creation of the International Ice Patrol (IIP) and the tracking of icebergs that threaten shipping. Aided by aircraft and satellite reconnaissance, the ice monitors have posted impressive results: In the past 103 years, no ship heeding the agency’s warnings has met the fate of the “unsinkable” liner.

But technology has its limits, especially off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, where fog can ground planes for days on end and coax “false positives” from orbiting probes. To help fill the void, the ice patrol relies on observations from ships at sea.

Michael Hicks, chief scientist for the IIP, said vessels play a key role in identifying icebergs that drift south of the 48th parallel north, which marks the nominal northern boundary of the trans-Atlantic shipping lanes. In 2014, the patrol received 67 iceberg reports from 47 merchant ships. In 2015, the total rose to 122 reports from 31 ships, with multiple reports from vessels assigned to oil and gas facilities on the Grand Banks.

“We’re looking out for one another, and what they report could very well prevent an iceberg collision,” Hicks said. “I think their reports are critical. While our planes can cover a great deal of area, there’s no substitute for visual observation by ship.”

Captains are encouraged to immediately report sightings of icebergs, or stationary radar targets that might be icebergs, to the nearest Canadian Coast Guard Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS) station. Data on the position, size and shape of each iceberg are entered into a computer model that predicts drift and deterioration.

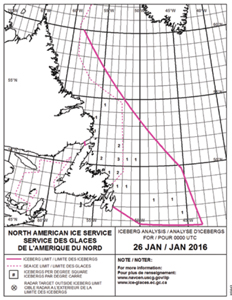

Using the model, the North American Ice Service — a partnership between the IIP, the Canadian Ice Service and the U.S. National Ice Center — determines a daily “iceberg limit” that is published in a text bulletin and chart for mariners. The information is distributed via SafetyNET, NavTex, sitor, email and the Internet.

|

|

Dan Morrisey, left, of the International Ice Patrol consults with Capt. Stepan Tumanov on the cargo ship Skogafoss. |

|

Rich Miller |

When a captain reports an iceberg that is outside the published limit, Hicks said the ice patrol works with MCTS to send an immediate warning to ships.

“Then we adjust our iceberg limit and update our daily product,” he said. “If we have an aircraft in the vicinity, we will certainly use it to check out the sighting. If not, it will become the focus of our next flight, whenever that might be.”

The IIP releases the iceberg bulletins from Feb. 1 through Aug. 31, which is typically the extent of the ice season. The Canadian Ice Service assumes the duty for the remainder of the year. Aerial patrols occur on the average of five days every other week during the ice season, with each flight covering 30,000 square miles or more. The reconnaissance is handled by C-130s deployed to Newfoundland from the U.S. Coast Guard air station in Elizabeth City, N.C.

Given the weather-related challenges faced by aircraft and satellites, the IIP is trying to encourage more captains to report icebergs through the Vessel of Opportunity Observation Program (VOOP). As part of that effort, Hicks and two IIP colleagues, Marine Science Technician 1st Class Steven Skeen and Marine Science Technician 2nd Class Dan Morrisey, visited the International Marine Terminal in Portland, Maine, in November to speak with the captain of M/V Skogafoss, a trans-Atlantic containership with ports of call in the U.S., Canada, Iceland and Europe.

As the Eimskip ship took on cargo, Capt. Stepan Tumanov told his visitors on the bridge that he was no stranger to icebergs, having reported one recently south of Greenland. He said he was familiar with the “iceberg limit” bulletins and charts, but was often too concerned with other tasks — including monitoring the weather and sea state — to call up the information every day.

The disclosure was important to Hicks, who said the ice patrol continues to work on ways to obtain more iceberg data and make it more accessible.

|

|

The North American Ice Service’s daily charts show the extent of drifting icebergs — also known as the “iceberg limit” — as a solid magenta line. The boxes with numerals inform mariners of how many icebergs are being tracked in that area; the dotted magenta line denotes the daily limit of sea ice. March, April and May are the peak months for icebergs drifting below the 48th parallel north. |

|

Courtesy North American Ice Service |

“Talking with the captain of a vessel is a very important link to understanding how our product gets used and how we might improve it,” he said. “That’s really the whole goal for us, to promote maritime safety and at the same time understand the captain’s need to facilitate commerce. We understand the balance behind that. We could draw our iceberg limit down to Bermuda and we’d be perfect, but it does no good for vessels transiting that area.”

Morrisey said feedback from captains helps make the charts “as tight as possible.” But even with the most accurate information, it’s not uncommon for a ship to pass through the iceberg limit. The captains of certain vessels have no choice — for example, those operating fishing boats or ships working in the oil and gas industry out of St. John’s, Newfoundland.

“Our dream is that people stay out of the area completely,” Morrisey said.

Hicks said the ice patrol set up the Portland visit after connecting with Eimskip at a September meeting of the North American Ice Service. The IIP attends the Connecticut Maritime Association’s annual conference to get the word out to shippers and captains, and it expects to visit other terminals once the ice season ends.

“We try to connect with our clients, if you will — the trans-Atlantic mariners — as much as possible,” he said. “We trust their professional judgment and we reflect that in our iceberg product.”