In the wheelhouse of the tug Donal G. McAllister, Capt. David Jurs looked on with admiration as another McAllister tug nudged a large container barge into its berth at the Seagirt Marine Terminal in Baltimore.

The tug Eileen McAllister had towed the container barge Columbia Elizabeth up the Chesapeake Bay from Norfolk, Va., arriving in Baltimore in late morning following the 181-mile overnight voyage. Donal G., a 3,000-hp former Navy YTB based in Baltimore, was on hand to help Eileen dock the barge. But with Capt. Richard (Rickey) Hinson at the controls of Eileen, not much help was needed.

|

|

The 123-foot twin-screw tug Eileen McAllister, rated at 4,000 hp, positions the container barge Columbia Elizabeth at a terminal in Philadelphia, the northern terminus of its route that begins in Norfolk and includes a stop in Baltimore. |

Eileen had come alongside the barge, with the tug’s port side tied up to the barge’s port bow. Hinson was using his tug’s twin screws to back the barge down and maneuver it against the dock. Donal G. stood ready to assist at the other end of the barge.

“Rick is really good,” Jurs said. “He won’t use us till we get really close to the pier.”

Jurs explained that Hinson was “twin-screwing the tug,” applying forward power to one prop while powering the other astern to exert a twisting force that would bring the barge closer to the dock. At the same time, one of Eileen’s crew was aboard the barge communicating with Hinson by radio, calling out the barge’s distance from the dock.

With a line up to the barge, all the single z-drive Donal G. had to do was apply a steadying force. “I was pulling his bow a bit,” Jurs said.

By 1230 the barge was securely moored, less than a half-hour after Hinson had begun maneuvering it to the dock. Its help no longer needed, Donal G. departed for McAllister Towing & Transportation’s base in Baltimore near Fort McHenry, a short distance away across the Patapsco River. Eileen, however, remained alongside the barge with an engine running.

Aboard Eileen, Hinson explained why. The cranes on the dock would soon begin the work of removing 114 cargo containers from the barge. The crane operator would have the challenging task of lining up the crane’s spreader — the device that attaches to the corners of the container — before lifting the box off the barge. Any shift in the position of the barge in relation to the pier would greatly complicate that task. “We keep one engine running and push into the lines that hold the barge steady,” Hinson explained.

So keeping the barge in position against the pier improves the efficiency of cargo loading and unloading. But there is another reason — to be ready to react in the event of an emergency.

Hinson recalled a time when a sudden storm blew up and drove the moored barge right off the dock. Because Hinson had an engine running, he was able to react and get the barge under control before any damage was done.

Growing up in White Stone, Va., where the tidal Rappahannock River joins the Chesapeake Bay, it did not take long for Hinson to find himself aboard a tug. “I’ve been working on tugboats since I was 17 and a half, my first week out of high school,” he said.

After all these years, Hinson is still at it and clearly enjoys what he does. He takes special pride in McAllister’s role in the container barge operation. Once a week, a McAllister tug tows the barge Columbia Elizabeth from Norfolk to Baltimore and back. And later in the week, the tug and barge do a loop that originates in Norfolk, stops in Baltimore and then continues on to Philadelphia by way of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal before returning to Norfolk.

|

|

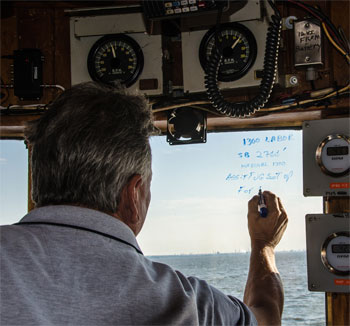

Capt. Hinson at the helm as the tug and barge prepare to pass under the two spans of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge on the approach to Baltimore. Hinson, who grew up along the shores of the Chesapeake in Virginia, has been working on tugs since he was 17. |

The container barge service is operated by Columbia Coastal Transport. McAllister does not own the barge. It simply tows it for Columbia Coastal.

The 343-foot-long barge has a capacity of 912 20-foot-long containers. Because containers actually come in a variety of sizes — typically 40 feet — the effective capacity is more like 600 boxes.

“I’ve had as many as 589,” Hinson said.

When the barge arrived in Baltimore on this day, it was carrying 349 boxes. After 114 were unloaded at Seagirt, the barge would depart for Philadelphia with 235.

Hinson is well aware of the environmental implications of moving the cargo by water rather than by land. “That keeps 200 truck drivers off the highway,” he said. “I know we use less fuel.”

The barge can also take heavy cargo that could not meet highway weight restrictions. “There’s no load limit on a barge,” he noted.

While Hinson is in charge in the wheelhouse, Richard LeThueur de Jacquant, the chief engineer, is in charge of keeping this 35-year-old boat running. For its age, it’s in great shape, LeThueur de Jacquant said.

Its two 16-cylinder EMD 645 E6 engines were rebuilt three years ago and have about 12,000 hours on them. The work was done at Colonna’s Shipyard in Hampton Roads, Va., and included installation of new propeller shafts. The boat is rated at 4,000 hp with a bollard pull of 51.6 tons.

“The engine room’s in great order,” LeThueur de Jacquant said, adding that the overall condition of the boat is good. “The shipyard made it so it will go at least another 10 years. They replaced a lot of steel.”

|

|

The tug leads its barge on a short towline as they pass up the C&D Canal at St. Georges, Del. |

McAllister has used it for a variety of towing jobs, including some long-distance work. LeThueur de Jacquant was aboard for voyages that Eileen made in 2010 to the San Francisco area to pick up ships from the U.S. Maritime Administration’s Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet scheduled for scrapping. The tug made two separate round-trip voyages lasting almost two months each to take M/V Winthrop Victory followed by M/V Bay out of San Francisco Bay, down the West Coast, through the Panama Canal, across the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico to Brownsville, Texas, where the ships were scrapped.

Those voyages were relatively uneventful, although on one there was a problem with the towing winch. “We lost the bearing for the level wind,” LeThueur de Jacquant said. “We had to cut it out while we were at sea.”

But the tug has proved itself to be up to whatever McAllister has asked of it. “They want to keep this as the main towing vessel for the company,” LeThueur de Jacquant said. “It’s very underpowered, but it still gets it done.”

LeThueur de Jacquant, a 2003 graduate of SUNY Maritime College, has been with McAllister for three years. Previously he sailed aboard deep-sea vessels, including containerships, tankers, research vessels and an ammo ship. His deep-sea career came to an end following his marriage. “Being at sea that long didn’t go that well with the wife,” he said. “After one year, no more.”

No longer away for many months at a stretch, he now works a schedule of three weeks on, three weeks off. And almost all of that is on Eileen.

“They don’t put me too many other places,” he said. And life aboard Eileen seems to suit him fine. “This one is actually very reliable.”

Just before 2100, Eileen and the container barge were ready to leave the dock at Baltimore and begin the second leg of the voyage to Philadelphia. Capt. Hinson took his position at the stern control station and carefully backed the barge out with the help of Kaleen McAllister, a 3,300-hp z-drive pulling the barge’s stern.

After paying out towline, Hinson swung the barge around. At 2105 he released Kaleen and a few minutes later, the tug and barge were bound for Philadelphia via the C&D Canal.

|

|

Mate Jim Stock navigated most of the nighttime transit of the canal as Capt. Hinson rested below. |

Hinson was in no hurry to get there. The berth for the barge in Philadelphia would not open up until noon the following day. He had 15 hours to make the trip of less than 100 miles. And when he reached the canal, the tidal current would be adding to the tug’s speed over ground. So the goal was to go just fast enough to maintain control over the barge.

“We’ll try to hold it at 7 knots,” he said. That would mean maintaining 620 to 630 rpm on the engines.

Navigating through the narrow and winding 14-mile canal would be challenging, but the real test would come as the tug and barge emerged into Delaware Bay. There a variety of winds and currents would be exerting one set of forces on the tug as it entered the bay, and a quite different set of forces on the barge in the more sheltered waters of the canal. But that was still some hours ahead.

While Hinson got some rest below, Capt. Jim Stock, the mate, would have the conn for the trip up the northern part of Chesapeake Bay and through the canal. Stock, who began working on tugs in 2005, got his mate’s license in 2008. He prepared for this leg of the voyage by entering the route in the electronic navigation system.

“Rick (Hinson) is going to have to go slow. We can’t touch the dock until 12,” Stock said.

He noted that during the trip from Norfolk to Baltimore, they were able to go much faster and operate with a longer towline (generally about 1,200 to 1,800 feet). With a shorter towline, the prop wash from the tug would have pushed against the bow of the barge, slowing the two vessels down. Here in the confines of the canal and at the slower speeds, Stock was working with the barge closer to the tug (100 to 150 feet).

Just as dawn was breaking, the tug and barge neared the northern end of the canal and prepared to enter Delaware Bay. Stock got on the radio to issue a sécurité call. “We’re giving everyone a heads up we’re going to be coming out,” he explained.

Because of the complications of wind and tide, the intersection of the canal and the bay is the trickiest part of the route. Stock had done his planning to bring the vessel to this point as close as possible to slack tide.

|

|

Chief Engineer Richard LeThueur de Jacquant, with one of the two 16-cylinder EMD mains with Falk gears. |

“Slack water was 20 minutes ago,” he said, noting that the tidal current now would have reached .6 knots.

At this point, with the tug making less than 8 knots, he announced, “All right, gentlemen, I’ve turned it over to the master.”

With that, Hinson, who had returned to the wheelhouse, took his place at the controls. As the tug approached the jetties that mark the end of the canal, the current coming up Delaware Bay would be pushing forcefully against the starboard side of the tug while the barge trailed behind in the canal.

“It’s like stepping on a treadmill sideways,” Hinson said.

That meant he would have to fight the tendency of the tug and the barge to get misaligned as the current pushed the tug to port. The barge might then exert a lateral, potentially destabilizing force on the tug.

“You almost have to wait for it to start happening and then correct for it,” he said. “It (the barge) is starting to come right of my track line.”

Hinson, of course, was able to maintain control while making it look easy. “She didn’t need any help,” he said of the barge. “I just need to stay in front of her. I’m still trying to get lined up.”

Things can get more complicated, such as his recent encounter with a sailboat as he entered the Delaware. Sometimes it’s necessary, he said, to “let the law of tonnage take over.”

That did not happen on this day and everything went smoothly. “I’m now lined up with the channel,” he said. “The barge is starting to settle down because the tide’s not pushing on the side of it.”

The tug and barge continued to make their way slowly up the Delaware. Just before 1130, Eileen made its rendezvous south of Philadelphia with the single-screw Teresa McAllister. Together they worked the barge to the dock on the western bank.

With Stock calling out the distances, Hinson had Columbia Elizabeth fast to the dock at 1210, right on schedule. With one engine running to hold the barge fast, Eileen McAllister stood ready to meet any challenge.