On a foggy day in the Houston Ship Channel, the pilot aboard Conti Peridot made an urgent radio call to his counterpart on Carla Maersk.

“Try to miss me, coming across the channel,” Conti Peridot’s pilot said, according to a National Transportation Safety Board accident report.

For an hour, the 63-year-old pilot had struggled to control the 623-foot bulk carrier but never informed the ship’s master or warned approaching vessels. With the 600-foot Carla Maersk nearing, the bulker was sheering toward it in dense fog. Both pilots tried to avoid the collision but were unsuccessful.

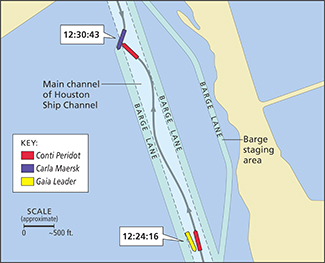

The inbound Conti Peridot struck the outbound chemical tanker at 1230 on March 9, 2015, in the channel near Morgan’s Point, Texas. The incident caused a spill of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and a combined $8.2 million in damage to the ships.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of the accident “was the inability of the pilot on the Conti Peridot to respond appropriately to hydrodynamic forces after meeting another vessel during restricted visibility, and his lack of communication with other vessels about this handling difficulty,” according to the report.

“Contributing to the circumstances that resulted in the collision was the inadequate bridge resource management between the master and the pilot on the Conti Peridot,” the report continued.

The Houston Pilots Association disputes those findings. Pilots spokesman Henry de La Garza said Conti Peridot’s pilot has safely directed 4,900 ships through the channel during his career and has thousands of hours of experience in the wheelhouse.

“We contend it was a lack of propulsion,” de La Garza said in a recent interview. “What caused the lack of propulsion? We believe the culprit is low-sulfur fuel.”

Conti Peridot’s transit was uneventful for much of the morning before the accident. The vessel safely met several outbound ships and was overtaken by another inbound ship without incident. Yet there were signs of trouble starting at about 1130 as fog worsened and visibility was reduced to about 800 feet. The first control issues arose after Conti Peridot met the outbound ship Karoline N.

“The pilot told investigators that, after meeting the Karoline N, the Conti Peridot ‘dove to the left’ as a result of the displaced water behind the Karoline N,” the report said. “The pilot told investigators that the bulk carrier then began reacting to bank effect and that he was ‘doing everything (he) could to control her.’”

Conti Peridot met another vessel about 10 minutes later, but by then the fog was thicker and visibility was down to 400 feet. Conti Peridot’s pilot told the pilot on the approaching tanker Stolt Span that he was coming off the bank. The tanker moved to the right side of the channel as Conti Peridot sheered left across the centerline, the report said.

The pilot regained control of his ship after that incident, but 20 minutes later he noticed three outbound ships were approaching one after another. Around this time, the pilot aboard Carla Maersk expressed concern about the fog and discussed with the master pulling off at Barbours Cut several miles ahead, but he soon abandoned the idea.

Concerns about the weather seemed appropriate. The Houston Pilots suspended boardings of inbound ships at 1120, and 15 minutes later the Galveston-Texas City Pilots also decided to suspend pilot boardings. However, those decisions did not affect outbound vessels or those already in transit.

|

|

A diagram compiled using AIS and VDR data shows Conti Peridot’s oscillating track line as it approached the tanker. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/Source: NTSB |

After meeting Gaia Leader, the first of the three approaching ships, Conti Peridot’s pilot told investigators his ship “dove into the void” left by the passing vessel. His ship was then “off to the races” with a series of uncontrolled motions from bank to bank.

As Carla Maersk approached, the second ship in the line of vessels, the fog was too thick to spot the vessel. The two pilots arranged a port-to-port passage, yet the pilot aboard Conti Peridot continued to struggle with his ship. He issued a series of rudder commands and also ordered the engines full ahead to get more water over the rudder to regain control.

“He shifted the rudder to hard starboard and, to achieve a better rudder response to this starboard command, ordered the engine to full-ahead speed,” the report said. “But despite the full-ahead and starboard orders, the Conti Peridot continued sheering to port, toward the Carla Maersk.”

At this point, Conti Peridot’s pilot warned his colleague and urged him to try and miss him by coming left across the waterway. However, Carla Maersk was already moving toward the starboard side for the port-to-port passage.

“Just seconds before the collision, the Conti Peridot began turning to starboard. The pilot on the Carla Maersk ordered the rudder hard right and the engine to full-ahead speed in order to turn as quickly as possible from the oncoming bow of the Conti Peridot,” causing the tanker to ground, the report said.

Still, those maneuvers weren’t enough. Conti Peridot T-boned Carla Maersk on its port side near midship, leaving a bow-shaped indent in the hull, breaching a cargo tank and damaging several ballast tanks. Up to 2,100 barrels of MTBE escaped from the Maersk tanker, causing a sheen visible in the water.

Carla Maersk sustained $5.6 million in damage, while Conti Peridot required about $2.6 million in repairs. No one was injured.

Control issues with Conti Peridot were documented two years earlier during a transit in the Houston channel. After that voyage, a pilot recommended that the bulker be trimmed up to 1.5 feet at the stern and suggested using an escort tugboat. These actions were not carried out the day of the accident.

However, the Houston Pilots Association has offered another theory about the cause. The pilots made the case to NTSB investigators about potential impacts from the low-sulfur fuel on Conti Peridot’s propulsion system. De La Garza said the pilot felt no response from his hard-right rudder and full-ahead engine commands just prior to the incident.

“Had the pilot been given the full-ahead bell as he ordered, the hard-right rudder would have likely been effective in avoiding the collision,” de La Garza said.

According to the NTSB report, the pilot never expressed problems with Conti Peridot’s engine performance during or after the voyage.

Investigators identified several problems with the voyage, particularly the pilot’s failure to let other ships know he was having control issues. They also cited the lack of communication between the pilot and the master aboard Conti Peridot. For instance, the pilot told investigators after the incident that he did not believe Conti Peridot’s master or bridge team were aware of the control issues.

Officials also determined dense fog was a factor by reducing visibility and increasing the “cognitive workload” of the Conti Peridot pilot. That in turn affected his ability to control the ship.

The NTSB also cited Vessel Traffic Service Houston/Galveston. Officials there “did not effectively monitor vessel traffic to identify the developing risk of collision during restricted visibility,” the report said.