It has taken decades to build the fuel supply chain for the 50,000-vessel global merchant fleet. The pending 0.5 percent sulfur cap on marine fuel stands to upset this entrenched structure, with price volatility likely as a result.

To comply with a 2016 regulation enacted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), vessels must either treat their exhaust, use an alternative fuel such as liquefied natural gas (LNG), or begin using fuel oil containing 0.5 percent sulfur or less by Jan. 1, 2020. Contained in Annex VI to the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), the regulation reduces the sulfur limit from its current level of 3.5 percent. In response, fuel suppliers have adjusted refining processes, while operators are adapting to changes in fuel prices and quality before the cap takes effect.

The sulfur cap forces bluewater operators in the United States to decide between opting for compliant fuel or burning high-sulfur fuel oil (HSFO) while using a scrubber system that removes sulfur oxide from exhaust, according to Kathy Metcalf, president and CEO of the Chamber of Shipping of America (CSA).

“Either option comes at a cost to a vessel’s budget, although it is predicted that scrubbers would pay for themselves … no longer than three years from the initial investment and installation,” she told Professional Mariner.

Installing a scrubber can cost anywhere from $2 million to $5 million. According to Metcalf, the expected price of compliant fuel could increase next year by at least 30 percent over current HSFO prices.

Vessels sailing within 200 nautical miles of the U.S. and Canadian coasts will continue to comply with the 0.1 percent Emission Control Area (ECA) sulfur limit that has existed since 2015. Given this history, Chamber of Marine Commerce President Bruce Burrows said he does not foresee many compliance issues in Canada next year. While most Canadian operators have decided to burn compliant fuel, he said the scrubber decision largely depends on fuel costs.

“If for some reason fuel costs skyrocket for low-sulfur fuel, then the notion to put scrubbers on (vessels) may be more attractive,” said Burrows, whose organization represents shipowners and fuel suppliers in Canada and the U.S.

According to Metcalf, the trend in the U.S. fleet is toward scrubbers. Adoption has not happened as quickly as expected, however, as a result of installation issues and environmental concerns related to open-loop scrubbers, which discharge washwater into the sea. Multiple government bodies throughout the world have banned open-loop scrubbers, the most common type of scrubber system, due to their impact on marine environments.

Connecticut and California have banned scrubber discharges in their waters, while Hawaii has enacted standards for washwater. The IMO has agreed to open discussions on harmonizing global rules governing scrubber discharges, and these talks are expected to conclude in 2021.

Metcalf did not have data on scrubber use for the 70 U.S.-flag vessels trading internationally. She said that about 15 percent of the global fleet will be using scrubbers in 2020 and that more U.S. operators are expected to adopt the technology next year.

In the tugboat sector, coastal operators should already be in compliance with IMO 2020 without the need for scrubbers. Most operators are already burning low-sulfur fuel oil (LSFO), and the Environmental Protection Agency limits sulfur content for marine diesel to 15 parts per million, said Caitlyn Stewart, regulatory affairs director with the American Waterways Operators.

Indirect impacts of IMO 2020 “could include fuel price fluctuations or changes in demand for fuel bunkering services that some of our member companies provide,” she said.

|

|

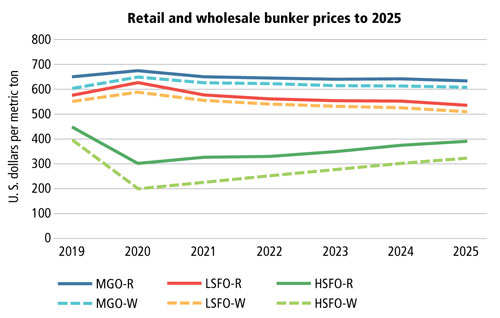

Prices are expected to decline for wholesale (W) and retail (R) high-sulfur fuel oil (HSFO) through the end of 2020, according to 20/20 Marine Energy. Increases are forecast for low-sulfur fuel oil (LSFO) and marine gas oil (MGO). |

|

Courtesy 20/20 Marine Energy/Pat Rossi illustration |

Price projections

Despite the move to scrubbers by some larger ships, Adrian Tolson, senior partner at consulting firm 20/20 Marine Energy, said LSFO should comprise the overwhelming majority of the fuel market.

“That means demand goes up for low sulfur and down for high sulfur (fuel), and it should, relatively speaking, impact the wholesale prices of those products accordingly,” he said.

The increased demand could push wholesale prices of LSFO from $550 per metric ton this year to $590 in 2020, according to predictions 20/20 Marine Energy shared with Professional Mariner in September. HSFO is expected to decrease significantly in price, dropping from $400 to an estimated $200.

A lot of unknowns exist, making accurate predictions difficult. But Tolson also said operators can expect volatility in the prices of HSFO and LSFO, especially during the first quarter of 2020, until the bunker supply chain becomes more defined.

Before the end of the current year, the number of fuel suppliers dealing in HSFO should gradually decrease, causing prices to rise. However, Tolson added, once demand crashes, the price will trend downward quickly.

“When that day is I have no idea, but that day will come,” he said.

While LSFO should jump in price next year, 20/20 Marine Energy’s projections show the wholesale price decreasing in subsequent years, dipping below $525 by 2025.

Ensuring fuel quality

According to Tolson, vessel owners should have no difficulty finding sufficient quantities of HSFO and LSFO at major ports.

In reference to LSFO, Metcalf said that “pockets of non-availability are expected in the short to medium term” for regions like South America, Africa and some parts of Asia that do not have sufficient refining capacity.

Coast Guard spokeswoman Lt. Amy Midgett said domestic fuel availability issues should be very limited.

For ship operators transiting internationally, “one of the keys to this transition is careful voyage planning that considers bunker availability to the maximum extent,” she said.

Operators have already started to address potential fuel quality issues as refiners begin to use new blends. Metcalf said fuel components may vary from refinery to refinery based on geography.

“The global cap is only focused on sulfur content, and other marine fuel criteria need to be considered as well,” she said.

The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) recommends that operators consider factors like compatibility and flashpoint to ensure safety and usability.

Compliant fuels with the same sulfur content but bunkered at different locations may not be compatible, according to the ICS. As a result, the organization recommends storing fuel orders in segregated tanks to avoid co-mingling.

The ICS also advises operators to verify fuel stability and flashpoint before bunkering begins. According to Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) regulations, fuels should have a minimum flashpoint of 60 degrees Celsius.

To avoid violating the sulfur limit, Tolson said that vessel owners who aren’t using scrubbers must clean their tanks of residual high-sulfur fuel as soon as possible.

For ships without scrubbers, the carriage of fuel with a sulfur content over 0.5 percent is prohibited after March 1, 2020, under the IMO regulation. Port states will enforce the 2020 sulfur cap, and the U.S. Coast Guard is obligated to do so as a party to MARPOL Annex VI. The current ECA enforcement mechanism will remain unchanged, and the Coast Guard will continue to review bunker delivery notes, check vessel logs and verify fuel changeover procedures, Midgett said.

While ensuring a compliant, competitively priced supply of fuel involves factors beyond operators’ control, Tolson said uncertainty can be mitigated through forward contracts. He suggested that shipowners develop a bunker plan and work with fuel suppliers to “lock in” supply and price as much as possible.

“It has to be an adaptable plan because nobody knows what the 2020 market will look like,” Tolson said. “So you really have to adopt some changes as we see different pricing and as we see different supply and demand signals come through.”