Seawater likely entered El Faro from multiple locations, according to a report presented during the third and final round of Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hearings that also described a “plausible sequence” preceding the ship’s sinking.

Testimony offered during the hearings, held over two weeks in February in Jacksonville, Fla., also focused on cargo loading, ship stability and the third-party organization responsible for inspecting the roll-on/roll-off vessel.

TOTE Maritime, parent company of El Faro operator TOTE Services, pushed back against some testimony during the hearings, particularly the claims that some cargo likely shifted during the voyage.

El Faro sank on Oct. 1, 2015, roughly 35 miles east-northeast of Crooked Island in the Bahamas while sailing from Jacksonville to San Juan, Puerto Rico. The ship lost propulsion as Hurricane Joaquin approached and crew could not get it running again. Twenty-eight sailors and five Polish technicians died.

TOTE has settled lawsuits brought by 29 of the 33 people on board but declined to discuss terms. The company said it has cooperated with investigations by the Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

“Our goal throughout the process has been to learn everything possible about the tragic loss of our crew and vessel,” TOTE spokesman Michael Hanson said. “We welcome any safety-related recommendation from these investigations that benefits all seafarers.”

Investigators from the Coast Guard and NTSB will use testimony from three rounds of Coast Guard hearings as well as information from the ship’s voyage data recorder (VDR). NTSB spokesman Peter Knudson said the agency hopes to release its findings later this year.

Whether the NTSB or Coast Guard will identify a probable cause remains to be seen. Based on what has been disclosed publicly, Capt. Larry Wade, the former captain on Maine Maritime Academy’s training ship State of Maine, doesn’t believe investigators have enough information to establish anything definitively.

“I think what they have to continue to do is run some simulations with all the data they have,” Wade said in a recent interview, suggesting that investigators could tailor the models to match the crew observations recorded on the VDR. “I think that is the closest they could come.”

The final round of Coast Guard hearings opened Feb. 6. Dr. Jeffrey Stettler of the Coast Guard Marine Safety Center presented a preliminary report that day on El Faro’s stability that offered a “plausible scenario” of what caused the ship to sink.

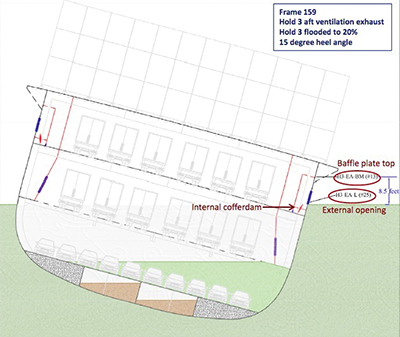

Stettler’s research suggests the following chain of events: The third cargo hold flooded, possibly through an open scuttle, contributing to the ship’s heavy starboard list in the storm’s strong winds. After losing propulsion and turning beam to the wind and waves, El Faro would have faced significant rolling.

“In this condition, eventually, (in) hold 2A and perhaps eventually hold 2 and hold 1, the ventilation supply exhaust openings would have immersed, allowing additional floodwater into hold 2A,” Stettler said during the hearings, noting crew conversations on the VDR transcript indicate that hold 2A’s bilge alarm sounded at 0716 on Oct. 1.

|

|

The summary of a preliminary report on El Faro’s stability and structures, prepared by the Coast Guard’s Marine Safety Center, includes the illustration above. Among key conclusions in the summary were that the cargo ship was “vulnerable to progressive flooding through cargo hold ventilation openings,” and that it was “unlikely to survive even single-compartment flooding of hold 3 with combined 70- to 90-knot winds and 25- to 30-foot seas." |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

Downflooding could have filled cargo holds and the engine room with seawater, and the ship likely would have begun slowly rolling over — a process potentially delayed when containers fell overboard. Stettler’s report concludes El Faro was vulnerable to “progressive flooding through cargo hold ventilation openings” and was “unlikely to survive even single‐compartment flooding of hold 3 with combined 70- to 90-knot winds and 25‐ to 30-foot seas.”

Later in the hearings, an official with Harding Lifeboat Services — now a Palfinger subsidiary — said crew likely did not deploy the ship’s open lifeboats before it sank.

The Alternate Compliance Program used by the Coast Guard to inspect some vessels faced scrutiny during the proceedings. The classification society ABS was responsible for inspecting the 40-year-old El Faro in cooperation with the Coast Guard, which had placed the ship on a “targeting list” for ACP issues shortly before it sank.

Inspections of El Faro’s sister ship El Yunque after the disaster identified rust and steel wastage in ducts and vents not reported to the Coast Guard. TOTE has since scrapped El Yunque. An ABS attorney noted that inspectors found no major structural or mechanical problems on El Faro, and TOTE’s attorneys pointed out the Coast Guard considered the ship safe to sail.

The National Cargo Bureau reviewed cargo-loading practices aboard TOTE vessels on behalf of the NTSB. The bureau determined “securing may have been satisfactory for most of the cargo if lashings were properly applied, but was not likely to be satisfactory for heavier pieces stowed off-button.”

For instance, some lashings did not appear to be properly applied at all times, and some lashings were not always attached properly to “points of equivalent strength on the cargo,” the report said. One of the report’s authors said it was “probable” that cargo shifted during the voyage, potentially causing a “domino effect” in which other cargo broke free.

TOTE disputed some claims about deficient cargo loading below decks, and National Cargo Bureau experts acknowledged they do not know what happened on El Faro’s final voyage. A TOTE attorney also asserted the report was conducted in a “factual vacuum” because the bureau’s report was limited in scope.

Wade, who spent 35 years sailing on oceangoing tankers and retired from Maine Maritime Academy in 2011, was glad that stability issues and third-party inspections were discussed during the hearings “instead of just blaming people.”

Wade said key takeaways from the investigations thus far are the importance of watertight integrity and the need for robust, accountable and frequent inspections. El Faro had just one emergency beacon, and Wade believes ships should be required “immediately” to have multiple units.

In the near future, he also believes ships should be required to carry modern voyage data recorders. Due to its age, El Faro carried a simplified VDR that captured VHF radio, radar and AIS information as well as speed, position and heading, but it did not record engine, steering, alarm, wind or hull integrity data.

Laurie Bobillot is optimistic that investigators will determine “what really happened” to the ship. Her daughter Danielle Randolph, 34, was a second mate aboard El Faro and a 12-year TOTE employee.

Bobillot cannot understand why the ship left Jacksonville with the storm approaching, or why Capt. Michael Davidson did not change course as Randolph and at least one other crewmember suggested, according to the VDR transcript.

“There are a lot of hands to blame in this whole damn thing, but what it comes down to is the almighty dollar,” she said in a recent interview. “Delivering that shipment cost 33 lives for a dollar in their pocket.

“They are going to have to answer for that in a bigger court system in the long run,” Bobillot continued. “When they go and meet their creator, they are going to have to explain that.”