Bridge audio captured by El Faro’s voyage data recorder (VDR), made available by the National Transportation Safety Board, offers new details about the tragedy.

The VDR transcript released in December provides a harrowing account of the ship’s last 26 hours, particularly its final 120 minutes when Capt. Michael Davidson and crew tried to correct a heavy list, identify the source of flooding and restart the main engine.

The transcript answers some lingering questions about the voyage but also raises new ones. For instance, it is now known that Davidson ordered crew to abandon ship about 10 minutes before the VDR stopped recording, but it is not known if anyone made it off the vessel.

Crew described flooding from an open scuttle on the second deck, but there is also mention of a ruptured fire main that might have worsened the flooding. The crew discussed the ship’s 15-degree starboard list and potential impacts on engine oil levels, but it’s still not clear what caused the plant to fail.

Capt. Joseph Murphy, who retired in December from Massachusetts Maritime Academy, remains convinced the drifting ship capsized very suddenly while taking a pounding from Hurricane Joaquin. But based on the transcript, he sees no single catastrophic failure that doomed the 790-foot El Faro. Rather, he believes the accident was a “classic cascade event.”

“One thing goes, then the next thing goes, then the next thing goes,” Murphy said in a recent interview. “If at any point along the way they were able to break that chain, the ship might have survived.”

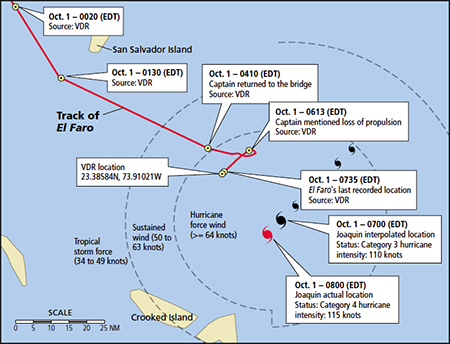

El Faro was sailing from Jacksonville, Fla., to San Juan, Puerto Rico with cargo containers, vehicles and trailers when it sank on Oct. 1, 2015, roughly 36 nautical miles northeast of Crooked Island in the Bahamas. At that point, the ship was 22 miles north-northwest of Hurricane Joaquin’s center. There were 28 crew and five Polish contractors on board and all hands perished in the accident.

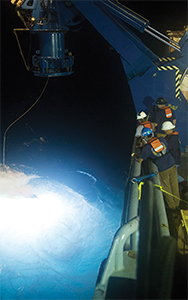

Authorities located El Faro’s simplified VDR last April, and they recovered it 15,000 feet below the surface in August. The device captured crew conversations, fax transmissions and other sounds from the bridge but in other ways was limited. For instance, the VDR registered radio and telephone conversations to other parts of the ship, although only what was said on the bridge was captured.

|

|

An NTSB diagram shows the ship’s route and key VDR data points. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/NTSB |

The NTSB released the transcript Dec. 13 along with reports detailing El Faro’s engineering system and lifesaving equipment. Other reports on the accident will be released in the future, officials said in December. Meanwhile, the Coast Guard is preparing for a third Marine Board of Investigation hearing into the accident scheduled for Feb. 6, 2017. Neither the NTSB nor the Coast Guard has released any final determination about the sinking.

El Faro’s parent company, TOTE Maritime, issued a statement after the VDR transcript was released describing the ship’s final moments as “heartbreaking.” The company also said it was clear its crew acted heroically.

“(We) encourage people not to rush to judgment because the transcript is raw data and the NTSB and Coast Guard are still conducting an official investigation, which we are fully supportive of and cooperating in. TOTE is hopeful the VDR information will help with the goal to learn everything possible about the loss of our crew and vessel,” the statement said, adding that TOTE would not discuss the issue further.

TOTE remains locked in a legal battle with the families of about a quarter of El Faro’s crewmembers. Jacksonville attorney Rod Sullivan said in mid-December that TOTE had settled wrongful-death cases with families of 24 crewmembers and was close to resolving a 25th case. The lawsuit brought by Sullivan’s client, the estate of Sylvester Carter, is still active.

The VDR transcript begins just before 0600 on Sept. 30, 2015, with Davidson and his chief mate discussing a course change intended to avoid the strengthening Joaquin. They agreed on a route further south and west than the ship’s standard route. Davidson also sought approval to take the Old Bahama Channel on the run back from Puerto Rico to Florida.

The course change did little to soothe El Faro crewmembers. Bridge crew on rotating watches spent much of Sept. 30 discussing the storm and the ship’s proximity to it. Several crew also monitored the storm on TV and weather websites while off watch. By 2023, the third mate and the ship’s AB-3 both seemed concerned about the ship’s position.

“It’s just I don’t like being so close to something here,” the third mate said, adding, “maybe I’m just being a Chicken Little. I don’t know.”

Crewmembers on watch received updated weather reports at about 2300 on Sept. 30 and 0120 on Oct. 1. On both occasions, they called the captain’s stateroom to provide the latest updates and in both cases Davidson declined a further course change. He believed the ship, sailing in Joaquin’s southwest quadrant, would get its winds at the stern.

|

|

CURV-21, the remotely operated vehicle that retrieved El Faro’s voyage data recorder, is lifted to the surface by crewmembers aboard USNS Apache on Aug. 8, 2016. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

The captain returned to the bridge at about 0410 on Oct. 1, and there were signs of trouble 30 minutes later. The first mate received word at 0437 that a trailer was leaning over on the second deck. Three minutes later, engine room personnel expressed concern that the heavy starboard list threatened engine oil pumps.

“I’ve never seen it list like this,” the alternate chief engineer said from the bridge at 0511. “You gotta be taking more than a container stack. I’ve never seen it hang like this.”

“We certainly have the sail area,” Davidson responded, noting the vessel was making about 11 knots in the storm, down from about 20 knots the previous day. Wind speeds weren’t available during the voyage because El Faro’s anemometer was not functioning. The transcript does not provide a clear description of sea conditions or wave heights.

The first mention of flooding occurred at 0543 with news that the No. 3 cargo hold was taking on water. The chief mate checked on it and reported back to the captain via hand-held radio. The transcript does not include the chief mate’s comments, although the captain said, “That’s a lot of water.”

Twelve minutes later, Davidson acknowledged flooding from an open scuttle on the second deck. The chief mate reported it closed at 0601 but soon went back down from the bridge to monitor the pumps. The situation went from bad to worse when the ship’s plant failed at 0613.

Davidson initially believed the engine would come back online relatively soon. But by 0654 the engine was still down, winds were battering the ship and “a significant amount” of flooding was reported in the No. 3 hold.

“They having trouble getting it back online?” the second mate asked at 0657.

“Yeah, because of the list,” Davidson responded.

|

|

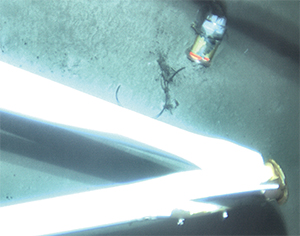

A photo taken by CURV-21 shows the VDR next to El Faro’s mast on the sea floor. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

Crew sent a formal distress signal at 0712, and two minutes later the chief mate reported the fire main had ruptured and water levels were rising down below. At 0717, the chief engineer reported the list seemed to be getting worse.

Davidson mentioned cars floating in the No. 3 hold and the chief mate interjected, “There are. They’re subs,” in a moment of gallows humor.

At 0719, the captain asked the chief engineer if they could isolate the fire pump because “that may be the root cause of the water comin’ in.” Six minutes later, the chief mate said water was chest-deep on the second deck.

Davidson sounded the general alarm at 0727 and a minute later he asked over radio that all crew get immersion suits ready. The second mate on the bridge spotted containers in the water at 0729. Seven seconds later, Davidson ordered crew to abandon ship.

Over radio, the captain ordered the rafts lowered and everybody off the boat. He urged crew to stick together. That message at 0731 was his last communication to them.

Davidson and the AB-1 were the last two people on the bridge recorded by the VDR. The helmsman appeared unwilling or unable to leave. The captain urged him onward and warned him not to panic.

“I’m gone,” the helmsman said loudly at 0739. “I’m a goner.”

“No, you’re not,” Davidson yelled.

The VDR picked up unidentified yelling and rumbling. Davidson again told the helmsman it was time to go. Two seconds later, at 07:39:41, the recording stopped.

Murphy believes Davidson showed “profound leadership” during the ship’s final hours and tremendous courage to stay on the bridge with the helmsman. Murphy believes few, if any, crew made it off the ship.

“The guy’s last act was to try to save a member of the crew. That’s what he was trained to do as a tradition of sea, and he adhered to it at the cost of his life,” Murphy said.

The VDR recording degraded as El Faro encountered the storm and background noise increased, and several key conversations were incomplete. At other times, the transcript provides one-sided communication between the bridge crew and engineering room. Murphy said this makes it difficult to get the full picture of what happened. Even so, he’s not sure crew knew the source of the flooding. He’s also not certain what caused the plant to go.

“By their own accounts, the loss of the lube oil resulted in the loss of the main propulsion. I think that occurred as a result of the list and the inability to get lube oil out of the sump,” Murphy said. “But without positive information, it is virtually impossible to determine … what happened.”

Although some crewmembers questioned Davidson’s decision to leave the bridge from about 2000 on Sept. 30 to about 0400 on Oct. 1, Murphy said that’s not especially unusual. The captain almost certainly left clear night orders and also urged crew to call him if any issues arose.

“He got up at a time before sunrise and (tried) to be prepared for what was going to happen,” Murphy said, adding, “I don’t find that unusual at all.”

Murphy praised Davidson’s poise and leadership but suggested the captain could have ordered crew to abandon ship sooner, which might have given them more time to launch survival crafts.

|

|

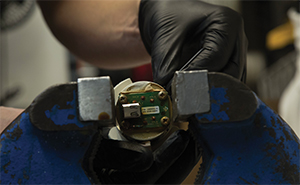

An NTSB engineer on USNS Apache works to remove the lid from the inner capsule assembly of El Faro’s VDR. Within the protective capsule is the memory chip that stores data. |

|

Courtesy NTSB |

“Absolutely positively across the board, additional training is required for all officers in stability and trim, damage control and survival procedures,” Murphy said. “They have to bolster the training they have in all these areas.”

Davidson’s decision to depart Jacksonville has been scrutinized in the months following the accident, and his decision to maintain course when crewmembers provided updated weather information likely won’t silence the critics. But NTSB investigators acknowledged El Faro received weather data from multiple sources, and the reports at times conflicted with each other.

El Faro’s email-based weather service, the Bon Voyage System, was transmitting forecasts that were many hours old. The ship also received text-based weather forecasts through the Inmarsat-C Safety Net, or Sat-C, program, which transmits by fax. The bridge also had SiriusXM radio that broadcast weather reports, and crew were following the storm on The Weather Channel and the website Weather Underground.

“The issue of exactly what information was available to the different crewmembers is still under investigation,” Jim Ritter, the NTSB’s deputy director of the Office of Research and Engineering, said during a Dec. 13 news conference.

Glenn Jackson, whose brother Jack Jackson, 60, died in the accident, has read the transcript several times and considers it “heartbreaking all around.” He believes his brother is the “AB-3” who told fellow crewmembers that his survival suit was out and ready.

“He was so prepared. He was … looking at the chart and looking at the updated weather forecast and getting ready,” Glenn Jackson said in an interview. “He had a great respect for the sea.”

Glenn Jackson remains critical of TOTE, which he said failed to provide modern safety equipment on the 41-year-old ship and failed to use a weather routing service. However, he hopes the tragedy can lead to safety upgrades across the U.S. bluewater fleet.

“If there are any other ships even close to that age, (I’d like to see that) these safety upgrades are made mandatory so this never happens again to a U.S.-flagged ship with a U.S. crew.”