The roll-on/roll-off ship El Faro went missing and is presumed sunk in the western Atlantic Ocean near the Bahamas after encountering Hurricane Joaquin. Authorities found no survivors among the 33 people on board.

The 790-foot vessel was about 35 miles north of the Crooked Islands in the Bahamas on Oct. 1. At about 0700 that morning, Capt. Michael Davidson told company officials on shore that the ship had lost propulsion, the hull had been breached and a scuttle had blown open. He said the vessel was taking on water and listing 15 degrees.

The Coast Guard received three automated alerts from El Faro at about 0717 that morning, including its emergency position indicating radio beacon, but never spoke with the captain. At that time, Joaquin’s eye was just 20 miles away from the ship. However, Davidson reported the ship was encountering 10- to 12-foot seas, authorities said.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has launched an investigation into the accident — the worst U.S. maritime shipping disaster since the disappearance of SS Poet in 1980, which claimed 34 lives. The investigation could take a year or longer.

The U.S.-flagged El Faro was owned and operated by affiliates of Jacksonville-based TOTE Maritime.

“We don’t have all the answers. I’m sorry for that. I wish we did,” said Anthony Chiarello, president and chief executive of TOTE. “But we will find out what happened.”

The exact cause of the sinking might never be fully known. However, experts believe the disabled ro-ro vessel, which carried 391 containers on its deck and 294 vehicles and trailers below, probably capsized. The Coast Guard said the disabled vessel could have encountered 140-mph winds and 50-foot seas before it sank.

“The ship, under those conditions, I am sure came broadside to the wind and was basically broached, and then it rolled over and sank,” said Capt. Joseph Murphy, an instructor at Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

|

|

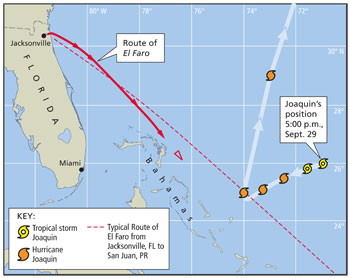

The path of Hurricane Joaquin. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration/Sources: U.S. Coast Guard, NOAA |

He believes many of the sailors’ bodies are likely trapped inside the ship. “They never would have had a chance to get into the lifeboat in those conditions,” Murphy said.

Capt. Robert Russo, who runs the Maritime License Training Center in Atlantic Beach, Fla., also believes the ship capsized. He ran five simulations that tried to match the onslaught facing El Faro. Although the Nautis simulator could not exceed 35-foot seas and roughly 70-mph winds, the vessel still capsized in all five simulations, each time within about nine minutes.

Russo was so surprised by the results that he called the manufacturer, who he said told him the simulation shows “the physics of what would happen.”

“Personally, I think that any vessel that is powerless is going to be broadside to the winds,” Russo said. “I can’t think of anything that would really survive that for very long.”

El Faro was built in 1975 to serve Alaska, and the vessel underwent significant upgrades in 2006. TOTE said the Coast Guard last inspected the ship in March, and the American Bureau of Shipping conducted hull and machinery inspections in February.

At the time of the accident, there were 28 crew and five Polish contractors on board El Faro. The contractors were preparing the vessel for transfer to the West Coast-Alaska trade. TOTE said the work was not related to the ship’s propulsion system. The vessel’s boilers were scheduled to undergo repairs in November.

At 2300 on Sept. 29, the National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane watch for parts of the Bahamas and warned the storm would intensify over the next 48 hours. By 0500 the next morning, 10 hours into El Faro’s voyage, the National Weather Service issued a hurricane warning for Central Bahamas.

At about 1312 the next day, Davidson told a TOTE safety official that his intended route was south of the storm’s predicted path, the NTSB said in an Oct. 20 update on the investigation. The captain expected to miss the hurricane’s center by 65 miles.

AIS trackline data from El Faro show the vessel maintained a straight route running on the east side of the Bahamas. The vessel’s path converged with the storm track early on Thursday, Oct. 1. At about 0720 that morning, the Coast Guard learned of El Faro’s tenuous state.

The U.S. military and TOTE Maritime undertook a massive search-and-rescue effort starting on Oct. 2 as Joaquin slowly moved away from the Bahamas. On Oct. 3, rescue crews reached the vessel’s last known location but still faced 100-mph winds and 40-foot seas, said U.S. Coast Guard Capt. Mark Fedor, chief of response for the 7th Coast Guard District.

Over six days, the authorities covered 183,000 square nautical miles using numerous military aircraft. During the search, the Coast Guard found an unidentified sailor deceased in a survival suit, whose remains were not recovered. Searchers found the ship’s life ring, ship debris and a heavily damaged lifeboat that showed no signs of life.

The second lifeboat has not been found, although experts have suggested it would have been extremely difficult to launch a craft in those conditions. Surviving in an open boat or a survival suit in those conditions would be extremely challenging, Fedor said.

The Coast Guard called off the search at sunset on Oct. 7. Fedor said the ship likely sank in about 15,000 feet of water near its last known location northeast of Crooked Island.

As of late October, the U.S. Navy was still searching for El Faro and its vessel data recorder near the ship’s last known location. The Navy planned to use side-scanning sonar, remotely operated underwater vessels and other equipment to locate the ship, the NTSB said.

In the days after the ship went missing, TOTE faced intense scrutiny for the decision to leave Jacksonville as the hurricane approached. On its website, TOTE said its crew was trained to respond to bad weather at sea, but it did not directly respond to those concerns. TOTE declined to make company officials available for an interview, citing the ongoing NTSB investigation.

Capt. Ralph Pundt, an instructor at Maine Maritime Academy, said captains consider myriad factors before departing, particularly when bad weather is possible. El Faro’s crew had access to real-time weather satellite data, TOTE said.

“But captains are always under the gun to sail to ensure that the charter agreements and on-time deliveries can be made,” Pundt said.

Davidson, 53, of Windham, Maine, was a Maine Maritime Academy graduate with more than 30 years of experience in the maritime industry, and 10 as a captain of large merchant ships. He joined TOTE three years ago. Prior to attending MMA, he worked as a deck hand and later was a captain with Casco Bay Lines, a Portland, Maine, ferry company.

Casco Bay Lines operations manager Nick Mavodones spent summers with Davidson as a child and the two later worked together at the ferry company. He described Davidson as “very prudent” in how he handled a ferry.

“Mike was a skilled captain who put the safety of the passengers and crew out there first,” Mavodones said in an interview.

Four other El Faro crewmembers also attended Maine Maritime Academy, which held a vigil to honor the ship’s victims. Two others aboard the ship attended Massachusetts Maritime Academy. Many other crewmembers lived in the Jacksonville area. Seafarers International Union (SIU) and American Maritime Officers represented El Faro’s crew.

In a statement, SIU President Michael Sacco said the men and women aboard the ship would never be forgotten. AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka praised the mariners for their hard work and commitment to the maritime trade.

TOTE has established a relief fund to help families of the crewmembers. The company also set up an education fund for children of the crew. TOTE said Seamen’s Church Institute will administer the funds, and 100 percent of proceeds will benefit the families.

Pundt, of Maine Maritime, said he’s encountered his share of 40-foot waves and blistering winds, but never close to those faced by El Faro’s crew and never without propulsion. In situations like that, he said, “you get real religious.”

“I think all mariners have encountered their share of rough seas and find peace in their own way, as they battle the elements. They rely on their ship and the captain to get them through,” he said. “To face that hell is what is keeping me up at night.”