Crowley Maritime’s El Coqui, one of the world’s first combination container/roll-on/roll-off ships (con-ros) fueled by liquefied natural gas (LNG), made its maiden voyage from Jacksonville, Fla., to San Juan, Puerto Rico, on July 27. Two weeks later, the newbuild from VT Halter Marine was back at JAXPORT, having completed three voyages to the island that is still recovering from Hurricane Maria.

The initial turnarounds for first-in-class ships are always busy, more so for El Coqui because of interest in the LNG propulsion, LNG bunkering and sophistication of the ship. Company executives, media, interested visitors, and vendors tweaking new equipment and complex systems populated the vessel. Add bunkering the LNG aboard while loading cars and containers, and you have a good deal of bustle.

The 720-foot, 26,500-dwt ship can transport up to 2,400 TEU in a wide range of box sizes — including 53-foot high-capacity containers and up to 300 reefers — at a cruising speed of 22 knots. At the same time, the ship can carry a mix of nearly 400 cars and larger vehicles in the enclosed, ventilated and weathertight ro-ro decks.

El Coqui is named for a popular frog indigenous to Puerto Rico. Taino, a sister ship under construction at VT Halter in Pascagoula, Miss., that is expected to join the fleet this fall, is named for the indigenous people of the island. The Jones Act ships, commercially managed by Crowley Puerto Rico Services and operated by Crowley’s Global Ship Management group, can make the voyage to the island in 54 hours. The company’s service by barge, in comparison, requires a six-day transit.

“Increasing supply-chain velocity while reducing customers’ landed costs was the core reason for our $550 million investment in this important service,” said Tom Crowley, company chairman and CEO. “Bringing this new ship, and soon its sister ship, to reality is one of the final steps to making this vision a reality. It should be evident to all that our commitment to Puerto Rico could not be stronger.”

|

|

Capt. Kurt Breitfeller demonstrates the procedure for docking from El Coqui’s port bridge wing as the ship takes on cargo at JAXPORT’s Talleyrand Marine Terminal. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

Wartsila Ship Design provided the engineering and design services for the new Commitment-class ships. Crowley’s solutions group, including naval architects and engineers from Jensen Maritime Consultants, a Crowley subsidiary based in Seattle, oversaw construction management at VT Halter.

“These ships were specifically designed for the Puerto Rico service, providing some of the fastest delivery times available in the market for the types of cargo our customers demand,” said Cole Cosgrove, vice president of marine operations for Crowley. “Speed, flexibility and a direct link to standard U.S. intermodal equipment make these vessels ideally suited for the Puerto Rico market.”

Cosgrove added that the new ships are a much cleaner method of transportation. When compared with current fossil fuels, LNG reduces emissions of sulfur oxide (SOx) and particulate matter (PM) by 100 percent, and nitrogen oxide (NOx) by 92 percent.

“There was a lot of design thought put into the fuel gas design, and our LNG fuel delivery system is different from others due to the degree of automation built into the system,” Cosgrove said.

The automation, in what is normally a manually controlled environment, introduces a greater degree of efficiency and safety for the operator and ensures the plant is operated with minimal environmental impact.

“The LNG industry has a stellar safety record and we want to make sure we maintain that,” Cosgrove said. “It’s a priority and it ties into our corporate culture.”

|

|

Cranes load El Coqui with containers at JAXPORT in mid-August. Facilities upgrades in Jacksonville and San Juan have greatly improved the ship’s turnaround times in both ports. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

To satisfy regulatory requirements, El Coqui is currently bunkering on every turnaround at the new Eagle LNG Partners terminal in Jacksonville. Eventually, fueling will take place every second trip. Reducing the number of fuel transfers by 50 percent will make life easier and safer for the crew.

“It also allows work on things like welding, chipping and painting on the off-fueling trips, tasks that can’t be done while bunkering any fuel type for safety reasons,” Cosgrove said. “There are also challenges to cargo when bunkering due to traffic patterns and additional equipment on the pier. But it makes the terminal and vessel crews more aware.”

While bunkering, water cascading over the hull shields it from the LNG line running up the side to the ship’s fuel line coupling. The water curtain protects the hull from the cryogenic effects of LNG in the case of a catastrophic failure of the hose or the connecting devices — for example, a ship pulling away from the pier while still connected to the fuel line.

“The connection device, called a dry disconnect coupling, is specially designed to not release any liquid at all, even if LNG is present in the hose,” Cosgrove said. “Because LNG turns to a vapor very quickly at ambient temperatures, only a significant failure would provide enough volume release to exist in a liquid state outside the transfer system.”

If a leak occurs, the LNG — at minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit — hits the water curtain, freezes and drops to the sea. If the fuel were to come in contact with the hull, the sudden temperature difference could cause the steel to crack.

|

|

Chief mate Jeremiah Lyons checks ballast levels while taking the list off the 720-foot vessel as it loads at JAXPORT. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

Of all the challenges to overcome in the building of the ships, the LNG fuel gas system was by far the largest, according to Cosgrove.

“We wanted the vessel to be indistinguishable as an LNG-powered vessel, so the location of LNG storage was a major design factor,” he said.

The conventional location for the LNG fuel tanks on a containership is on the main deck aft of the superstructure, such as on TOTE’s Isla Bella and Perla del Caribe from General Dynamics NASSCO, the first LNG containerships built in the United States. On the Crowley ships, that is where the four aft ro-ro decks and the stern vehicle-loading ramp are located. After looking at several options to put the LNG fuel tanks elsewhere, the designers eventually positioned them below the aft ro-ro decks, a location with little or no regulatory guidance history.

Cosgrove said aspects of the process required the cooperation of designers, Crowley, the classification society DNV GL and the U.S. Coast Guard, as well as engine, fuel gas, tank and automation suppliers.

“This project required determination, perseverance, understanding, cooperation and the teamwork of hundreds of people to make it a reality,” he said. “First in class sounds great, but achieving it is not for the faint of heart, or the impatient.”

VT Halter was chosen as the shipyard because it agreed to build custom-designed ships to fit Crowley’s vision, rather than shipyard-designed vessels.

|

|

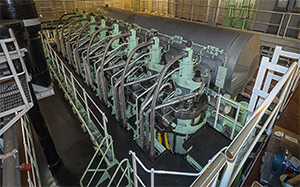

El Coqui’s MAN B&W 8S70ME-GI dual-fuel engine delivers more than 28,000 horsepower at 91 rpm, giving the ship a service speed of 22 knots. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

“The first challenge was that there was not a mature set of rules for gas-fueled ships when we started the design of the ship,” said Buck Younger, vice president of engineering for VT Halter. “So we used IMO Interim Guidelines MSC.285(86) and U.S. Coast Guard Policy Letter 01-12.”

Getting Coast Guard approval to put the LNG tanks and gas-handling equipment below the main deck in the aft cargo hold — to accommodate the enclosed ro-ro decks above — was the main issue because it had never been done in the U.S. The gas-handling equipment is in a separate fire boundary room from the engine room for safety reasons. The engine room is classified as a gas-safe space.

“It wasn’t difficult getting approval, but it involved discussions with the Coast Guard during concept design so that they could sign off and provide a design basis letter that was used to develop the detail design of the ship,” Younger said.

During the process, VT Halter was working with design groups from around the world: Wartsila for ship design from Norway and Poland; MAN for the main engine, generators and gas system from Denmark; and Tractebel Gas Engineering (TGE) for the gas system design from Germany.

“The challenge was to manage the different design teams, especially when we got to the detail design,” Younger said. “We had three working 3D product models to integrate. But that all worked out better than we expected.”

|

|

El Coqui can transport an assortment of nearly 400 cars and larger vehicles in its four enclosed and ventilated ro-ro decks. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

Younger added that navigating the regulatory process between the Coast Guard and DNV GL worked out very well and is a credit to both entities.

Also complicating the workflow was the supply chain for equipment, most of which was not available from U.S. manufacturers. The LNG tanks were made and shipped from India; the gas system equipment and parts are from the U.S., China and Germany; the MAN engine was built in Japan, and the three MAN generators are from Korea.

“A lot of thought went into the design of this ship to make it useful to the people (aboard),” said Crowley Capt. Kurt Breitfeller. “It was not a cookie-cutter design. It was designed for service and speed. … LNG is the cutting edge and it’s great to be here at the beginning. The forethought on design was phenomenal. And it’s Jones Act: American built and American crewed, American jobs.”

El Coqui is manned by licensed personnel from the American Maritime Officers and unlicensed crewmen from the Seafarers International Union. Breitfeller said that 50 percent of the crew are residents of Puerto Rico.

“They want to do a great job supplying the island, helping their families and helping the environment,” he said.

With a sweep of his hand taking in the breadth of the bridge console, Breitfeller said that every aspect of the ship can be monitored and controlled from there.

|

|

VT Halter Marine’s mark on El Coqui will be duplicated on sister ship Taino, which is scheduled to enter service in the Jones Act trade to Puerto Rico by the end of 2018. |

|

Brian Gauvin |

“There is built-in redundancy with multiple backups,” he said. “It’s very important, and most of the systems switch over automatically, which gives me peace of mind.”

The only diesel the ship burns is to ignite, or prime, the LNG fuel. Switching from LNG to diesel, and vice versa, for the main engine and the three generators is an automatic and seamless operation.

“The ship doesn’t slow down or anything,” Breitfeller said. “The only indication that the fuel has switched over is a little yellow light to let you know that it has happened.”

An important component of Crowley’s commitment to supply Puerto Rico with efficient, reliable service is the upgrades to terminals at JAXPORT and San Juan. The company installed three new gantry cranes at its Isla Grande Terminal on the island and built a 900-foot-long, 114-foot-wide concrete pier for mooring ships. Before the improvements, it took an average of 45 minutes for a trucker to transport a container into the terminal. Now, it takes 12 minutes. The turnaround time for El Coqui at each terminal is 24 to 28 hours.

“We have great shoreside support, which means a lot,” Breitfeller said. “Everyone is working to make the operation better. The ship is super fast and comfortable, and the shoreside facilities for ship operations are great. We are at the same spot every time, here in Jacksonville and in Puerto Rico. It makes it very efficient.”