Federal investigators said an ineffective maintenance regime that failed to identify wear on an aging towboat’s port-side clutch likely caused a collision in 2019 between two tows on the Lower Mississippi River.

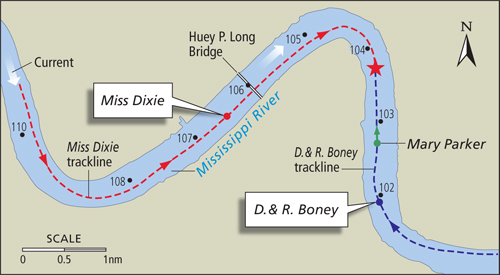

Miss Dixie was downbound with five barges when its lead barge struck the first of nine barges pushed by the upbound towboat D. & R. Boney. The collision happened at 1917 on Feb. 13, 2019, at mile marker 104 near Carrollton Bend in New Orleans.

Four barges were damaged, resulting in repair costs that reached almost $300,000. Several barges broke away and were retrieved by the crews of the two towboats. No injuries were reported on either vessel, and there was no pollution.

JRC Marine acquired the 58-year-old Miss Dixie about six months before the collision, and during that time the company did not inspect the clutches or establish a maintenance plan to ensure they were in good condition, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined.

The probable cause of the collision “was the lack of an effective maintenance program aboard Miss Dixie, resulting in excessive and undetected wear of the port clutch, which compromised the vessel’s maneuverability,” the agency said in its report.

|

|

Damage to the port bow of AEP 7235. |

|

NTSB photo |

JRC Marine and vessel owner Hex Stone could not be reached for comment. American Commercial Barge Line, which owned D. & R. Boney and operated it through a subsidiary, Inland Marine Service, declined to comment on the findings.

Miss Dixie left Baton Rouge, La., on the morning of the incident pushing five barges loaded with rock. The tow was arranged with three barges on the port side and two on the starboard side. That same day, D. & R. Boney left a fleeting area near Poydras, La., with nine barges carrying fertilizer, aluminum and diesel fuel. The port string was five barges long and the starboard string was four long.

Miss Dixie passed under the Huey P. Long Bridge at mile marker 106 at 10 knots. The captain prepared to meet the oncoming Mary Parker tow “on two whistles,” meaning starboard to starboard, a maneuver considered common around the hairpin turn at Carrollton Bend.

Miss Dixie and D. & R. Boney, which was behind Mary Parker, hadn’t yet agreed to a passing arrangement when Miss Dixie’s captain noticed the vessel’s steering and propulsion systems weren’t responding around Carrollton Bend. Meanwhile, a deck hand noticed smoke and possible fire in the engine room. Investigators said the captain rang the general alarm and requested to meet D. & R. Boney port to port.

“The captain of D. & R. Boney repeated the request and said, ‘It don’t look good for that’ and ‘I sure wish you’d go for the two, but all right, I’ll shoot her over,’” the report said. “Five seconds later, D. & R. Boney’s captain said that he was going to stop his vessel because the vessels would collide if they attempted to meet port side to port side.”

|

|

The location of Miss Dixie, D. & R. Boney and Mary Parker about 17 minutes before the incident, along with tracklines leading to the star marking the collision site. |

|

Vessel Traffic Service/Pat Rossi illustration |

D. & R. Boney’s captain put the engines full astern while Miss Dixie’s captain reported over radio that he “lost an engine.” About 30 seconds later, the lead barge in each tow collided. Miss Dixie’s deck hand later reported to the captain that the port-side clutch “burned up.”

Authorities determined that the clutch caused the smoke in the engine room. A service technician who examined the clutch after the incident identified “excessive wear” that would cause slippage. The clutch, the technician estimated, was 40 percent operational.

“After the accident, based on the location of the smoke and the reduction of power from the port propeller, the crew believed that the clutch had been slipping and overheating, which reduced thrust to the port propeller,” the NTSB report said. Such a failure aligned with the captain’s reported loss of steering and propulsion around Carrollton Bend.

JRC Marine told investigators Miss Dixie’s engines were overhauled before the firm bought the vessel. There was no indication the clutches were inspected or maintained during the company’s six months of ownership, and the owner later admitted the manufacturer’s recommended protocols were not followed.