The Coast Guard is investigating why a tugboat sank so rapidly in the Atlantic Ocean off Long Island that one of its crew did not have time to don an immersion suit and died.

Three crewmembers were rescued after putting on survival suits and abandoning ship when Sea Bear began taking on water off Fire Island on March 14.

“The survivors have been interviewed but it’s tough to say at this point,” said Lt. j.g. Martin Betts of Sector Long Island Sound, referring to why the 1,000-hp tug sank.

“Apparently, they were taking on water pretty quickly. I can’t speculate on why he could not put on the immersion suit. That’s part of the investigation.”

Betts said answers should be forthcoming once Sea Bear is recovered from the ocean floor.

The 23-year-old tug is owned by Wittich Bros. Marine Inc. of Brielle, N.J. Company executive George Wittich said in April that the firm has awarded a contract to salvage Sea Bear as soon as the weather permits, but he declined further comment while the casualty is still under investigation.

The 65-foot vessel was traveling from Hampton Bays to New York City after completing a dredging project in Moriches, the Coast Guard said. When it began to sink about a mile off Fire Island Pines at 1415, a member of the crew called the Coast Guard Vessel Traffic Service in New York, which relayed the mayday to Sector Long Island Sound in New Haven, Conn. Watch standers issued an urgent marine information broadcast and dispatched an MH-60 Jayhawk helicopter from Air Station Cape Cod, a 47-foot motor lifeboat from Station Fire Island, and a motor lifeboat and 25-foot boat from Station Shinnecock.

The Fire Island crew were the first to arrive on scene at approximately 1445. They discovered a debris field, despite poor visibility, and at 1554 took aboard the three survivors who were huddled together around two life rings in the 37-degree water. Donald Maloney, 60, of Pennsylvania, one of two captains aboard that day, was found unresponsive at 1709 by Willie Lander, another tugboat that had joined the search. Maloney was taken to Station Fire Island and pronounced dead by the Suffolk County Medical Examiner’s Office.

The other captain, Lars Vetland, 43, of Staten Island, and crewmembers Jason Reimer, 38, of Leonardo, N.J., and Rainer Bendixen, 22, of Bay Head, N.J., were treated at Station Fire Island for hypothermia.

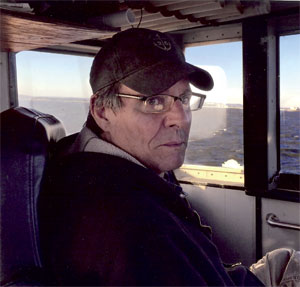

Maloney was an experienced and careful mariner from a family of tugboat skippers, said his brother Kevin, himself a tug master.

“His whole career was tugs,” said Kevin Maloney, 58, of Sayville, Long Island, a captain working out of New York Harbor with Vane Brothers of Baltimore. Maloney said he, Donald and a third brother, Steven, all grew up working on the tug Altoona operated by their father, Donald W. Maloney Sr., who died in 2005.

Donald worked on and off for Wittich and other towing companies, occasionally taking time off to help his daughter, Corrine, with her health care after she lost a leg to cancer.

Kevin Maloney said he has still not learned from any of the survivors or company executives why the boat sank or exactly where his brother was and what he was doing before it went down. “I guess when they pull up the vessel, the Coast Guard will get an idea of what took place,” he said.

Maloney said the surviving crewmembers and Wittich executives who came to the funeral all agreed there was no way that Donald had panicked, as some news accounts had stated, which was why he never got into his immersion suit.

“He was very cool and calm. Nobody said that he panicked,” said Maloney, who learned of the accident while he was working in New York Harbor that night through calls from other captains in the close-knit towing community. “Donnie and I worked together in different places, and we were in worse situations (than Sea Bear sinking). He handled those situations very well. Guys have come up to me and said ‘He started young and he was good at what he was doing.’”

Maloney said his brother was very safety-conscious and mentored young mariners. “We always knew it could be a dangerous business. You try to teach the fellows about the close calls,” some involving family members, he said.

“Once Donnie was asked to take a barge from Hempstead Harbor to the city and he turned it down because of high seas,” he said, “and then another fella on another tug said he would take it, and that boat needed to be rescued because it was taking on water.”

Kevin has a photo of the Red Star tug Devon that went down with his father aboard on Aug. 31, 1960, when it was going to the aid of the tanker Helen Miller near Hell Gate in the East River. Devon was rammed by another tanker, Craig Reinauer, and went aground off Wards Island where all seven aboard were rescued.

Steven Maloney, now a Miami resident, was a deck hand on the tug Morton Bouchard when it sank in the Cape Cod Canal after it was “tripped,” or struck, by the barge it was towing, according to Kevin Maloney.

While Donald Maloney had never encountered any serious marine incidents before Sea Bear sinking, Kevin recounted once seeing a crewman putting out running lights as a tug was tying up to two barges on the Hudson River, with the man ultimately ending up in the water. “We stopped the boat and called the Coast Guard,” said Kevin Maloney. “I looked between the two barges and saw the running light was laying on its side and I saw something in the water in the gap, and I pulled it up and it was the sweatshirt of the fellow being crushed between the two barges.” That crewman was killed.

“I had another situation where a kid was on a dredge and they were letting go of the tug and all of a sudden they were releasing the stern line and the kid got his fingers caught between the line and the bitt,” he said. The crewman lost his fingers.

Maloney said he was mate on a tug going into the Cape Fear River in North Carolina when a towing cable parted in 18-foot seas. He volunteered to go onto the barge to re-establish a connection. “I timed it to jump onto the dredge, and there were acetylene bottles flying all over,” he recalled. “The adrenaline is flowing and things are happening. But you do the things you have to do. That’s part of the business.”

He said his brother would have been too busy trying to stop the leak on Sea Bear to panic. “The first thing going through your mind is, ‘How do you stop the flow of water coming in?’ If you can’t do that, the next step is get the life raft out and put on your survival suits.”

Donald Maloney was cremated. In addition to his daughter and brothers, he is survived by another brother and his former wife, Carolyn Maloney Badke of Centereach, N.Y.