George H. Ledcor was towing a loaded gravel barge up the Fraser River as the vessels approached a bend near Richmond, British Columbia. The tug turned to port, but the barge continued on a straight heading.

The captain ordered the assist tug pushing the barge’s stern to back off, then applied full throttle and full starboard rudder as the barge began to pass the tug’s starboard side. Barge Evco 55 soon overtook George H. Ledcor on its starboard side, however, and the towline began exerting a broadside force on the tug. Attempts to release the tow weren’t successful, and the tug capsized at about 2210 on Aug. 13, 2018.

“Within seconds, the tug’s deck edge and bulwarks were submerged, creating a dragging force that heeled the tug further to starboard,” the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) of Canada said in its report issued in October. “The tug rapidly capsized.”

All four crew escaped the vessel, including the mate and a deck hand sleeping below deck. They were picked up by the assist tug Westview Chinook and a nearby good Samaritan vessel, River Rebel. One of the two deck hands suffered a serious hand injury, and an unknown amount of diesel reached the waterway. George H. Ledcor was declared a total loss.

The TSB identified several issues during its investigation, including a persistent girding threat among Canadian tug operators. From 1991 to 2018, the TSB recorded 38 incidents of girding that resulted in 30 capsizings and five fatalities, the report said.

The twin-screw, 770-hp George H. Ledcor left Sechelt, British Columbia, at about 1645 on Aug. 13, 2018, after Evco 55 loaded 4,621 metric tons of gravel. The destination was a gravel depot at Mitchell Island. The towline was connected to Evco 55 via a Y-bridle secured to the barge’s port and starboard sides. The 950-hp Westview Chinook assisted the tow by pushing on the barge’s stern.

George H. Ledcor’s captain shortened the towline to roughly 50 feet as the vessels approached the north arm of the Fraser River, just south of Vancouver. The vessels navigated through two bends and were approaching a third when the captain sensed the barge was not turning to port as expected.

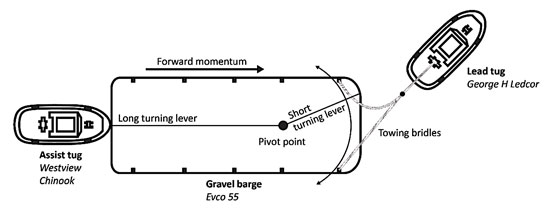

Evco 55 “continued on a straight course and began to overtake the tug, at which point the short towline, which was not secured by a hold-down gear, began to exert a broadside force on the tug, placing it in a girded position,” the TSB said.

|

|

The assist tug Westview Chinook was only pushing Evco 55, not guiding it, when the girding incident occurred. The TSB said Westview Chinook applied a longer turning lever and had more influence on the direction and momentum of the barge, in a straight line, than George H. Ledcor. “As a result, the lead tug, with its shorter turning lever, was unable to turn the barge,” the agency said. |

|

TSB illustration |

The report added that the captain did not have time for corrective action before the tug started to roll. The captain and the deck hand on duty also lacked time to activate the general alarm, make a distress call or put on life jackets.

The agency suggested the towing arrangement hindered George H. Ledcor’s ability to turn the barge; the shortened towline meant the tug exerted less turning force. Conversely, the report said, the assist tug was better suited to maneuver the barge given its longer turning lever.

Both the captain and deck hand attempted to release the winch brake in the moments before the tug capsized. The captain could not reach the wheelhouse abort button due to the tug’s starboard heel, and the deck hand reportedly pressed a button on the aft controls that did not release the winch. Post-incident analysis showed the winch abort system was not activated.

The report does not say if the deck hand pressed the correct button. However, the TSB noted that the abort buttons were in different parts of the control panels across all three conning stations. Ledcor has since standardized the placement of the abort mechanisms on its tugs.

George H. Ledcor’s captain earned his master’s license eight years before the incident. During the intervening period, he did not receive training or guidance from Ledcor on avoiding or responding to girding situations. According to investigators, the company considered girding and ways to respond to it common knowledge.

“When the barge began to overtake George H. Ledcor, the master attempted to use steering and propulsion to reposition (the tug) in front of the barge,” the report said. “However, a number of factors acting on the vessel’s stability increased the vessel’s heel: thrust from the course alteration, flow of the river against the hull, and continued broadside force of the towline.”

The TSB said training on girding avoidance and response is key to ensuring that crews are prepared when these situations arise. To that end, Ledcor has taken steps to highlight this issue among its maritime workforce. These include adding girding avoidance to its safety management system and holding crew meetings on the topic. Ledcor also instituted a two-day training session on girding that includes time in a simulator for its mates and captains.

Ledcor, a diversified construction company based in Vancouver, did not respond to an inquiry about the TSB findings.