Crew aboard Star of Abu Dhabi dropped anchor at a Mississippi River anchorage on a clear spring evening following a long voyage from the Canary Islands. Soon afterward, the captain signaled he was finished with the main engine.

The overnight hours did not go as planned.

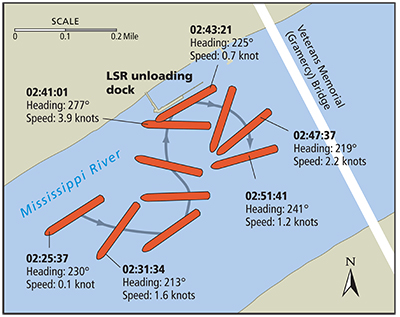

The ship’s port anchor chain parted at about 0230 on March 25 and its starboard anchor began dragging. Eleven nerve-wracking minutes later, the bulk carrier slammed into a loading dock near Gramercy, La., before continuing downriver. Its movement stopped after the engine came back online.

The impact opened a 14-by-7-foot hole in vessel’s hull above the waterline, causing about $232,000 in damage. The Louisiana Sugar Refinery dock fared worse: It partially collapsed and cost $4.6 million to repair. U.S. authorities briefly arrested the Panama-flagged ship after the incident.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators determined Star of Abu Dhabi used two means of holding position at the anchorage despite a local marine bulletin requiring three during high-water conditions present at the time. The NTSB cited the captain’s failure to make sure the engine was in standby mode as the likely cause of the accident.

“The Star of Abu Dhabi used two means of holding position: its two anchors,” the agency’s report said. “The propulsion system was not in standby, although the master believed the engine was on 10-minutes’ notice.”

Star of Abu Dhabi arrived at the Lower Grandview Anchorage at mile marker 146 on the evening of March 24. It was carrying phosphate rock and was waiting for a berth at a fertilizer plant roughly 40 miles upriver. At the time, the swollen Mississippi River was at 15 feet in New Orleans and rising, which spurred the Coast Guard marine safety information bulletins.

The pilot from New Orleans-Baton Rouge River Pilots (NOBRA) ordered the port and starboard anchors dropped with four shots of chain in the water. Four shots were in the water on the port anchor, but the starboard anchor chain had four shots on deck — roughly 40 feet shorter. The report said the difference in scope created uneven tension on the anchor lines.

“A jerking motion or shock load can break a chain, whereas a constant load is less likely to cause a break. Given the longer scope of chain and the current on the port bow, the port anchor chain was likely taking the majority of the strain,” the report continued.

By 2200, the ship was anchored and the captain ordered “finished with engines” on the engine telegraph. The pilot did not address the captain’s order before departing but recommended the ship’s bow remain pointed toward the east bank, the report said. The pilot also said the ship engine’s should stay on short notice.

|

|

The track of Star of Abu Dhabi compiled from AIS data, shows the ship dragging anchor and striking the Louisiana Sugar Refinery dock near Gramercy, La. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration |

After more than four uneventful hours, the ship swung to port at about 0230 when its port anchor chain parted. The captain returned to the bridge at 0238 and gave a 10-minute order to restore engine power.

“At 0240, VTS (vessel traffic service) informed the vessel that a pilot had been ordered. About the same time, a slight vibration was heard and felt as the bulk carrier’s starboard side allided with the LSR raw sugar unloading dock,” the report said. “A minute later, the master announced the vessel’s starboard quarter was on the LSR dock and sounded the emergency signal.”

The chief engineer returned to the engine room shortly after the accident, and seven minutes after impact the engine was online and the ship was under control. Afterward, tugboats helped the vessel remain in position at the anchorage with one anchor.

The ship’s chief officer inspected the mooring winch and anchor windlass less than three days before the accident and found no issues, the NTSB said. ClassNK certified the anchor chains and kenter shackles connecting each shot of chain in 2012. The most recent survey was in 2014 at a Chinese shipyard.

A metallurgist who studied the broken chain link determined “the fracture was caused by fatigue initiated by the chain link rubbing on the anchor chain stopper, and not an overload failure caused by a material deficiency or abnormal loading condition.”

Although the captain believed the ship’s engine could be ready on 10 minutes’ notice, he apparently never made that clear to the chief engineer. During the overnight hours, only an unlicensed engineer, who lacked authority to restart the engine, was on duty.

“The chief engineer indicated that if the engine was in standby, a licensed engineering officer would have been in the engine room on watch and the engine would have been available for immediate use by the bridge,” the report said.

The ship’s captain claimed he was unaware of marine bulletins requiring three means of holding position at anchor, but investigators said he “should have recognized the risk posed by the strong current and taken measures to ensure the vessel was ready to respond to an anchor-dragging situation.”

Abu Dhabi Shipping International S.A. of Japan owns the 11-year-old ship, and Fairmont Shipping Canada Ltd. operated it. A spokesman for the Vancouver, British Columbia, operator declined to comment on the NTSB findings, citing ongoing litigation.