The steamboat Delta Queen was built in Glasgow on Scotland’s storied Clyde River in 1926 to a classic Mississippi River boat design, broken down into components, and reassembled on the other side of the Atlantic for service on California’s Sacramento River linking San Francisco with the state capital.

Twenty years later, a 5,000-mile journey down the California coast, through the Panama Canal and across the Gulf of Mexico, brought the steamboat to New Orleans, where the sternwheeler has plied the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, off and on, ever since.

A half century after the iconic ‘steam kettle’ was built, a son of the same Scottish city received a degree in mechanical engineering and imagined he’d ply his trade on Britain’s rail system.

After all, he thought, as a journeyman he would have steady and secure employment, good pay with lots of perks like free rail travel, and work with high-speed passenger trains.

But, instead, a diverting option emerged one cold, rainy work day when a young Jimmy McFadyen, a budding railroad engineer heard a ship’s whistle in the harbor.

“I could leave and see the world,” he recalls. “It’s hard to say where the idea came from, but I decided I wanted to be shipboard. As a journeyman engineer, I had the basic knowledge and skill-set to work and thrive anywhere.”

Eventually, McFadyen submitted his paperwork to the Board of Trade, packed his belongings, and boarded Port Auckland, a Scottish-built Port Line refrigerated cargo steamer bound for New Zealand for what was supposed to be a be a routine three-month turnaround.

But a New Zealand longshoremen strike, the Indian Ocean rescue of an errant Maldivian ferry, and a 1973 war blocking traffic through the Red Sea stretched that trip into an epic lasting more than a year – an experience at the start of a career that would last decades.

More than wanderlust, McFadyen was convinced that his marine engineer’s ticket would help make his dream of seeing the world a reality even though none of the steps along the way could be foreseen and they would produce the makings of a collection of sea stories that begin less with “once upon a time” than they do “you’re not going to believe this…”.

McFadyen’s half-century career sea story means too many adventures and misadventures to list, but a few memorable jobs along the way bear mentioning with marine engineering basics that remain the same no matter the vessel, and Jimmy, as he’s known, was determined that his first voyage would not be a predictor of the trips that lay ahead.

His next ship carried passengers and kept to a better schedule. To his good fortune, the gleaming, white-hulled Pacific Princess would soon be better known to people worldwide as the ‘Love Boat.’ Even the floating stage for a television show comprising 250 episodes spanning 10 seasons needs an engineering department to keep the vessel steaming, the water and food hot, the laundry and plumbing operating, and the air conditioning and lights on.

Not in the job description, McFadyen adds that “sometimes for crew talent night, even this Scottish engineer would clean up, don formal whites and kilt, play the accordion, and even dance with guests. I have a souvenir photo with Lorne Greene, a star on the show.”

Of course, not all engineering assignments involve kilts or dress whites. “A job in Brazil some years ago was a terrible logistical nightmare in a miserable climate,” he said. Rolls Royce sent him to Manaus to repair one of their Aquamaster steering systems on a tractor tug because he’d had training on relevant systems in Finland and Sweden.

“People don’t understand how big and dangerous the Amazon really is, tough for Panamax ships to navigate with limited channel markers.” Tractor tugs are needed to assist during the week-long, nearly 1,000-miles voyage from the mouth of the River to Manaus. The disabled tug was in a shipyard near Manaus, where a repair crew had dismantled the unit and, for whatever reasons, could neither repair nor reassemble the steering system.

“Besides the challenge of language, there was stifling heat,” said McFadyen. “My hotel had an industrial-sized air conditioning unit, it kept me cool, but it was noisy. I had to sleep with earplugs. We took breakfast on a roof terrace, very scenic, but it was already over 100 degrees F.”

The workers at the yard “used no PPE and flipflops was the norm for footwear. The yard had no cranes. Mid-afternoon all my help would disappear to buy food whenever the small fishing boats came in,” he said.

Specialized gears and bearings were flown in from Finland and had to be precision-installed with the lifting equipment they had on site – an improvised system of rope and pulleys. “It took a month,” he said, “but we got the job done. The tug went back to work in the Amazon, and I flew home, wondering whether I had chosen the right occupation.”

The answer was a resounding, ‘Yes’ that has reverberated over the years.

As port engineer for General Dynamics, he managed the engineering functions on two SL-7 fast surface ships near New Orleans, the USNS Bellatrix and USNS Pollux.

The SL-7s ships were originally built in Germany for Sea-Land Service in the 1970s and, retrofitted with on-board cargo-handling cranes, currently serve as part of the Military Sealift Command’s Ready Reserve Force.

“European shipyards have a history of first-rate workmanship, superb quality control, and the best electronics,” said McFadyen.

“These SL-7s are the fastest conventional steam-powered cargo ships in the world, capable of speed in excess of 33 knots. The engineering is first-class.”

When orders came, he added, “We had four or five days to get them from ROS (reduced operating status) to FOS (full operating status), ready to depart on a mission, crewed up, and steaming away as fast as 90 hours.”

A naturalized U.S. citizen since 2003, McFadyen’s patois is the result of an “accelerated process” he attributes to working on and near the Mississippi River.

Other shipyard work farther up the Mississippi River and tributaries introduced McFadyen to the culture of U.S. inland shipping.

Those jobs led to consulting work with the Disney Corporation, writing the technical specifications for Walt Disney’s Richard F. Irvine, a replica Mississippi-style steamboat.

However, working on a Disney steamboat is not nearly as impressive as what preceded. The pride in McFadyen’s voice is palpable when he talks about this Scottish marine engineer’s job of a lifetime – working on the Delta Queen, like himself, a transplanted Glaswegian.

“Being port engineer on the Queen was fantastic, a fun job,” he said. “The major challenge was finding replacement parts, especially since the boilers were built in 1919, and the cross-compound engines in 1925.”

The problem was solved when an advertisement for spare parts led to a telephone call from a machine shop in Memphis that had parts for the vessel that had been stored in their warehouse since the 1940s. The current shop owner’s father had, in fact, machined them many years prior.

“Now the old gal is moored in Houma [Louisiana] and has been there too long.” The Queen has been at the shipyard since early April 2015, and according to McFadyen, “there’s no evidence of work being performed” despite reports that discussions are ongoing with a group of investors to restore the vessel and sail the rivers once again.

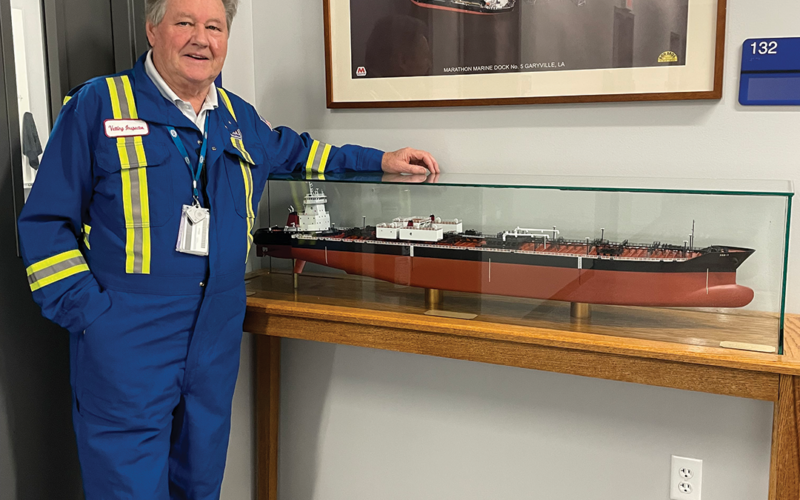

Currently, McFadyen works at Marathon Petroleum’s Garyville, La., terminal as a Ship Inspection Report (SIRE) inspector, vetting and surveying vessels transporting petroleum products.

SIRE is an oil pollution risk assessment tool used by charterers and terminals and was developed by the London-based Oil Companies’ International Marine Forum.

After half a century, it might be hard or near impossible to identify the single seed that sprouts into a life-long career. But for Jimmy McFadyen, it’s simple when he remembers a rainy day in a Glasgow train yard, working on a 100-Class diesel locomotive, and hearing a distant ship’s whistle.

He followed its call, and as he reflects on his journey, the sights he’s seen, and the ships he’s sailed on, he still wonders whether more ports of the world are beckoning.