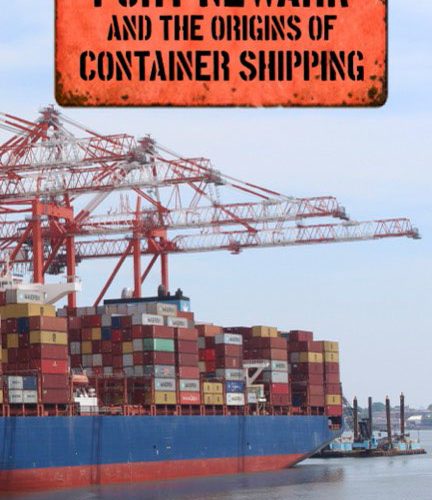

The development of containerization was a major change in transportation technology — an innovative idea with profound consequences for world trade. It all got started at Port Newark on April 26, 1956.

It was a chilly day, with a high temperature of 48 degrees, with intermittent showers. On a dock outside shed 154, some fifty-eight 33-foot-long containers were swung aboard the SS Ideal X, a converted World War II oil tanker, a 524-foot-long ship, with the previous name of Potero Hills. Previously, oil tankers would carry a profitable load of oil from Houston to Newark, but they would make the return trip with only ballast, something heavy to improve the stability of the ship. Now tons of cargo could be carried on the southbound trip, making both legs of the voyage pay. A huge crane placed the containers (they were understandably called “trailers” at that time) on a metal platform of the tanker, above the pumping machinery.

It was not necessary to put the whole trailer on the ship. Instead, everything underneath each trailer would be removed to save space. The trailers would be removed from their steel beds, axles, and wheels. All that was left was the trailer bodies, and these could be stacked. At the end of the trip, the trailer body could be lowered onto an empty chassis and driven away to its destination. Later that evening, the ship left for Houston, where it arrived six days later at City Dock 10.

The average loading time was seven minutes per container. The whole ship was loaded in less than eight hours. Under normal circumstances, the freight on the ship would have gone to Houston in over-the-road trucks — a trip of about six days. It would take the ship the same amount of time, but there would be a tremendous savings of about 30 percent. It was a breakthrough — the brainchild of one man, Malcom McLean. How did he come up with such an original idea? In his favor was the fact that he had no experience in shipping. He was an outsider, a truck driver.

To understand McLean’s thinking, we have to go back in time to his early life in rural North Carolina. He grew up as a farm boy, one of seven children. The son of a farmer who also worked as a mail carrier, he early on learned the value of hard work. His mother began raising a few chickens, sharing a dozen or two with family and friends. Gradually, she began reaching cash-paying customers. Young Malcom helped by acting as salesperson, earning a small commission. Graduating from high school in 1931, during the depths of the depression, he had no money for college, so he took up work at a local service station pumping gas. Life was a struggle, but before long, he had saved up enough money to buy a used truck for $120. His career in transportation was launched, and he began calling himself the McLean Trucking Company.

McLean got started by hauling topsoil, manure, produce, and livestock for his hometown farming community of Maxton. He soon gained a reputation for reliability, and he acquired five additional trucks with a team of hired drivers. This move enabled him to stop driving himself and to start reaching out to new customers. For a while, he seemed to prosper; but, as the depression deepened, he lost customers and he had to resume driving. Things were bleak, and it looked like he might lose his business altogether.

To survive, McLean started accepting long-haul contracts, requiring him to be away from home days at a time. In November of 1937, just before Thanksgiving, he got a job hauling cotton bales from Fayetteville, in southeastern North Carolina, to Hoboken, in northern New Jersey, then a major trans-Atlantic port. After a long drive, he arrived in Hoboken, joining a long line of trucks waiting to be unloaded at the pier at the foot of Third Street. The mixed cargo was being placed, piece by piece, aboard the Examelia, an America Export Lines ship that would take everything to Istanbul. The line moved slowly and there was not much to do. He had to wait hours to unload this truck trailer. Years later, he recalled, “I had to wait most of the day to deliver the bales, sitting there in my truck, watching stevedores load other cargo. It struck me that I was looking at a lot of wasted time and money. I watched them take each crate off the truck and slip it into a sling, which would then lift the crate into the hold of the ship.”

This oft-quoted sudden realization was the birth of an idea that would take a full 19 years to blossom into fulfillment. During that time, McLean focused on his trucking business. However, his perceptive intuitive thinking separated him from others in that business. He had plenty of time to think and plan. By the early 1950s, McLean had built his company into the largest trucking fleet in the South, with 1,776 trucks and 37 transport terminals up and down the East Coast.

Malcom McLean was known for his meticulous attention to cost information. He tracked his costs very carefully, so he always knew how his trucking business was doing. This habit enabled him to make well-informed business decisions about the future. Looking back at those early days, his protégé, Paul F. Richardson, said, “I don’t think anyone in this period had a better sense of north-south costs than Malcom. For 10 years and more, he personally watched his trucks like a hawk. He knew every angle of costing. It is a fair question of whether he was thinking at that time about ships-versus-trucks: how much cheaper it might be to put trucks on ships. Certainly, he had the figures in front of him all of the time. Every truck that went out was an object lesson for him. He could do the figures for a run standing by the truck cab.”

McLean’s first idea was simply to drive the trailers on board a ship. You could roll the trailers on at the point of origin and then roll them off at the destination, a process known as “ro-ro.” As he was mulling this concept over, he placed a telephone call to Brown Industries, a manufacturer of truck trailers in Spokane, Wash. He spoke with Keith Tantlinger, the vice president of engineering at the firm. It was a significant conversation. Tantlinger held a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of California at Berkeley. During World War II, he had worked for the Douglas Aircraft, designing warplanes.

Malcom explained his idea about driving tractor trailers onboard a ship.

Tantlinger said, “Why not just lift them on board and leave the wheels behind?”

McLean said, “Can you do that?”

Tantlinger said, “Sure, I can. I can even stack them, one on top of another.” •

Angus K. Gillespie is a professor of American studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Port Newark and the Origins of Container Shipping was published by Rutgers University Press. It is available through Amazon and other booksellers.