Fires while aboard a ship are a serious hazard that concerned mariners have to train for — and, in the event of an emergency, fight with while out on the water. Protecting the vessel and crew can come down to having the right equipment, proper training and appropriate systems in place.

Technology and innovative designs have helped progress firefighting tools and training, while mariners are also learning to comply with new regulations and deal with new threats.

Some notable advancements on the issue include SAFFiR, an autonomous, two-legged, shipboard firefighting robot developed by Virginia Tech with Office of Naval Research funding. AI algorithms for its functionality were provided by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

Autonomous firefighting can also translate to the vessels themselves. The world’s first autonomous-command, remote-controlled fireboat debuted at a 2018 event in Denmark. The 40-foot ProZero workboat was outfitted with an SM300 autonomy system from Boston-based Sea Machines Robotics as well as remote-controlled fire pump equipment.

Another lifesaving technology was launched in May 2022 from an Australian-based company and has been making waves due to the developers’ innovation.

Sarah Battenally, CTO, director and secretary of Manderson Engineering Innovations Pty Ltd., along with co-founder James Manderson, designed the Breach and Attack Tool (BAT), a portable penetration device and method to fight compartment fires at sea.

“BAT differs from other fire suppression technologies, as it is a genuinely novel fire protection product that allows firefighters to indirectly attack a compartment fire,” Battenally explained in an email to Professional Mariner. “The BAT product is gas-tight, can be remotely activated and could increase fire suppression capabilities on all maritime platforms.”

The design is compatible with all suppressants and interchangeable hose connections. It can aid all spray nozzles, water-mist nozzles, CO2, dry chemical foam and inert gases. Its non-spark rupture disc protects the crew from fire escalation during penetration.

The developers have yet to deploy it on board any commercial vessels; currently, their focus is on designing and engineering the technology to provide it to the Royal Australian Navy and allies who serve in maritime military operational environments. The technology certification requirements for military acquisitions differ from those of commercial vessels, Battenally noted, so they haven’t pursued International Maritime Organization (IMO), Lloyd’s or other flag-state requirements yet.

“However, we have secured a small order from a leading defense maritime prime in Australia,” she said. “We plan to pivot to commercial maritime vessels once we can ensure we meet military requirements, and our Australian and allied Navy service men and women have in their arsenal our innovative tools to help them fight and win at sea.”

The BAT design has an international patent filed and a patent pending on nine of the accompanying Deck Box configurations for fire suppression in compartment fires as well as battery storage for thermal runaway.

“We look forward to preparing more research on the Deck Box configurations, and aspire to utilize restricted (computational fluid dynamics) fire modeling using event tree analysis to build confidence intervals for human reaction timings, optimized training and suppression efficacy of our technology.”

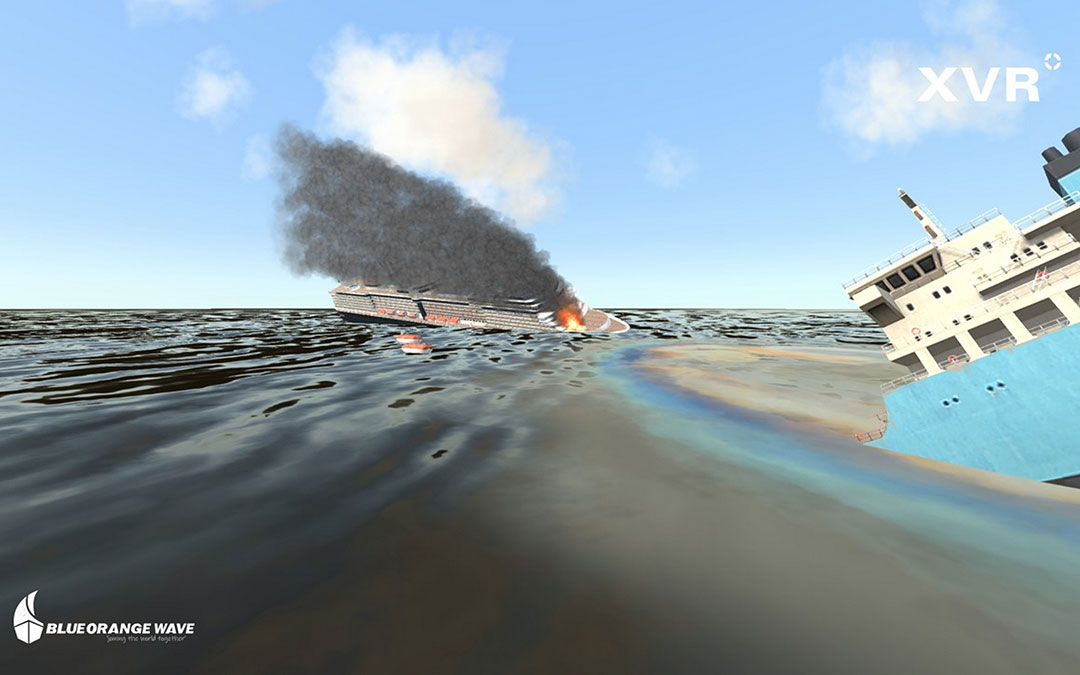

In terms of training for an emergency fire event aboard a ship, other innovative developers are looking to virtual reality (VR).

Tim Lodder, CEO of Blue Orange Wave, a global provider of immersive and innovative maritime safety solutions, emphasized in a recent interview with Professional Mariner that VR can help ship captains and crewmembers achieve better situational awareness and enhance the learning experience during firefighting training.

“We see it growing, and I also believe that virtual reality is the way forward for firefighting training (in the commercial maritime industry),” Lodder said.

Lodder developed the updated Dutch maritime safety training standards to comply with the IMO Standards of Training and Certification of Watchkeeping requirements, which included allowing the change from real-life firefighting exercises into VR training courses. They’ve gone through the process several times to get approved elsewhere, including the U.S. In New Orleans, for example, the Maritime and Industrial Training Center at Delgado Community College offers training and courses using technology from XVR Simulations.

Virtual reality, Lodder said, can be a digitally created rendering or an environment of real imagery stitched together using a 360-degree camera.

A VR video scene can help crewmembers learn about firefighting equipment, including details such as the information displayed on fire extinguisher labels, in their own environment on board a ship, Lodder explained.

“We can place any type of learning object in that environment,” he said. “You’re virtually in the exercise space, like in an engine room or on the bridge of a ship, and you can look around (and interact with the equipment) and learn something about a particular (piece of equipment).”

In more advanced courses, the user can learn about incident command, leadership and decision-making. Strategic thinking is emphasized in these courses, which help students develop focused skills that can be critical in an emergency situation.

It all comes down to the client’s learning goal, Lodder emphasized.

“I really believe that the use of virtual reality helps seafarers get a better understanding of a fire situation on board ships,” he said.

While real-life training scenarios are limited to what they can safely recreate, he noted that VR can create a wide variety of situations and regulate different elements — wind direction, type of fuel, proximity of hazardous materials, etc. — while enabling the user to easily replay and pause scenarios.

Virtual reality training is also more environmentally friendly: Since the “smoke” is computer-generated, it’s not releasing any contaminants into the air, Lodder added.

In an example scenario, Lodder used VR to simulate a fire on a containership. With a few simple clicks, he controlled variables such as wind direction, water level and temperature. The user can steer the vessel or add color to the water to simulate a chemical spill. He shared views from the bridge and deck, with details that can be adjusted to the ship.

“It gives you an idea of how simple it can be, virtual reality doesn’t have to be difficult,” Lodder said.

It’s a simple process to create a variety of situations where the crew would need to make decisions — and take action — on things that aren’t included in typical fire drills, he noted. There are too many variables during fires or other emergency situations on board ships for traditional training to cover them all, he added.

Being immersed in that type of experience will create learning moments that people will remember during a real-life situation, Lodder noted.

There have also been recent updates to the regulations and new chemicals used in some classic firefighting equipment, noted Jerry Dzugan, executive director of the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association.

Requirements for how much fire-extinguishing agent is needed to put out a certain size fire has changed in recent years, Dzugan explained in an email to Professional Mariner.

Modern tests of the effectiveness of extinguishing agents have demonstrated that the old standards were overrated for the given amount of agent, he noted. Therefore, the industry is going through a transition phase and mariners that have to replace fire extinguishers shouldn’t be surprised if a larger size is needed in order to meet carriage requirements.

“Overall, this is a good thing, since the required minimum carriage requirements for extinguishers for most vessels is quite minimal — especially considering that, at sea, you are the fire department,” Dzugan said. “Don’t be a cheapskate when buying extinguishers and avoid plastic extinguishers, which tend to have more recalls and failures, especially in the harsh climate and cramped conditions on a vessel.”

There are also new fire threats that mariners need to be aware of. “As the M/V Conception fire has tragically demonstrated, rechargeable lithium and other batteries are the emerging fire threat on any vessel,” Dzugan noted, alluding to the 75-foot passenger vessel that caught fire and sank while moored overnight off Santa Cruz Island, Calif., in 2019. The incident resulted in the death of 33 passengers and one crewmember.

The number and quality of electrical outputs on vessels have not kept up with the large increase and need for more onboard electronic gadgets with rechargeable batteries, Dzugan explained. Also, the quality of power strips used to plug in all of these devices varies widely, and most were never designed to be daisy-chained together with such large and flammable loads, he added.

“Not only vessels but homes have been lost just because one off-brand cellphone recharger was left unattended and overheated,” he said.

Dzugan shared a few ways to mitigate the rising threat of these types of fires, including not leaving recharging electronic items unattended and keeping combustibles away from charging stations.

This new fire threat also reinforces the importance of ensuring smoke alarms and wiring systems are properly installed and maintained, he added.

“Give your wiring system some love,” Dzugan said. “Very quickly, wiring systems get jury-rigged and mismatch-sized wires, connectors, fuses, etc. Don’t expect a wiring system to handle a load of rechargeable batteries that didn’t even exist when the wiring system was first designed.”

He also recommended taking time to imagine where a fire might start on the vessel. “Ask yourself what can be done to mitigate the hazards, what can be upgraded or replaced, and how the alert and evacuation process would work if there was an emergency. It’s also vital to keep up with training and fire drills,” he added.

“Drill for the emergency like it could happen to you,” Dzugan said. “There is no reason on earth why it wouldn’t.” •