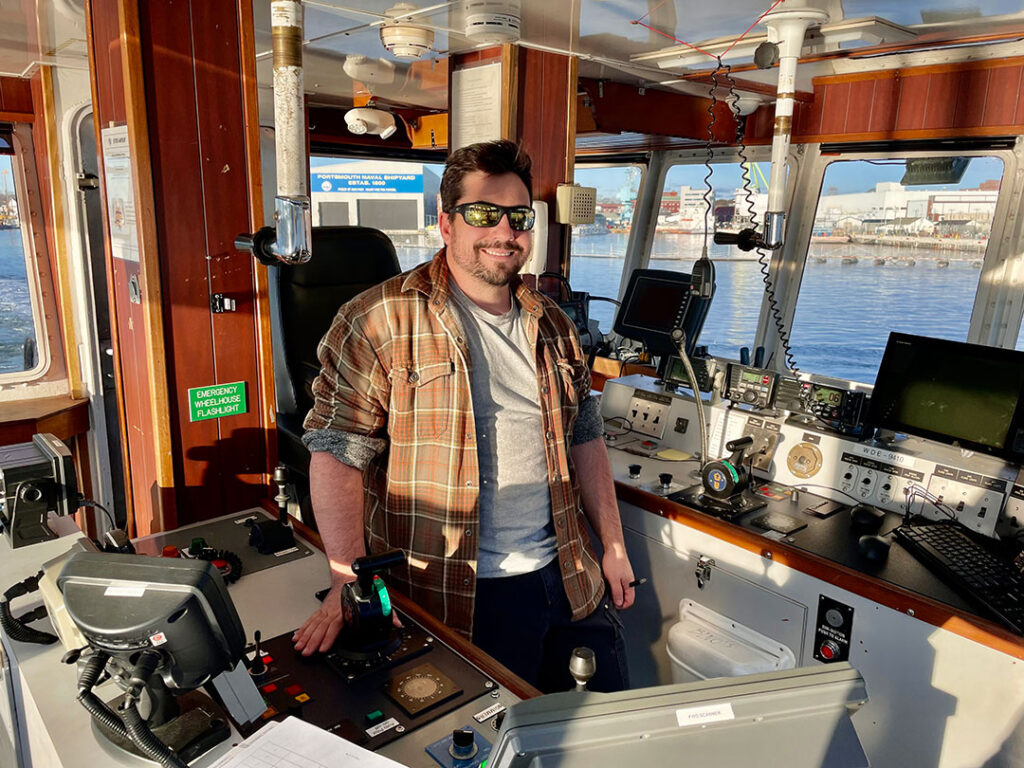

Capt. John Reeves wasted no time getting the tugboat Z-One underway in downtown Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Like fellow Moran Towing Capt. Matt Brewster, who would soon depart aboard Handy Four, Reeves had a schedule to keep.

Some five miles away, the inbound tanker New England was nearly ready to transit up the Piscataqua River to a Portsmouth oil terminal. Running late is not an option in the narrow Piscataqua, where tidal currents run up to 4.5 knots and ship movements happen around slack water. Missing that window can delay a ship by 12 hours or more.

“With a big ship we have to be on time,” explained Capt. Dick Holt, a fifth-generation mariner who serves as Moran’s Portsmouth vice president and general manager and a state pilot.

“Any vessel over 32 feet is a high-water slack tide movement only,” he added. “There is a strong tidal current here, and we move with about one hour of current with any large vessel. Every six hours we can move a vessel if the draft is 32 feet or less.

“Long story short,” he said, “if the draft is over 32 feet, it is a high-water slack water transit required, which is every 12 hours.”

Right on time, Reeves got Z-One underway on a sunny, brisk New Year’s Day afternoon. The 4,000-hp z-drive Z-One and 3,400-hp conventionally driven Handy Four represent half of Moran’s Portsmouth fleet, which until recently featured multiple single-screw workhorses.

Moran’s tugs occupy a prominent place on the Portsmouth waterfront and the historic city’s identity. The vessels tie up alongside the aptly named Tugboat Alley, in the heart of the working waterfront now characterized by tourist shops, high-end restaurants and higher-end condos. Images of the iconic maroon and forest green tugs adorn postcards, calendars, and other shots of the city. There’s a tugboat-themed children’s book set in Portsmouth and even a tugboat mural at the Children’s Museum of New Hampshire in nearby Dover.

Getting out to the Atlantic Ocean from Portsmouth takes some doing. The 35-foot-deep channel makes a series of doglegs around rocky islands and shallow ledges. Three bridges connect New Hampshire and Maine across the Piscataqua, two of which are lift spans that must be raised for vessels to transit through.

The channel passes Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, which dates to 1800 and is the oldest continuously operating naval base in the United States. Countless signs of the region’s proud maritime history line both sides of the river, including Fort McClary and Fort Foster in Maine, and Fort Dearborn and Fort Stark in New Hampshire. The forts collectively defended the region against hostile navies for centuries.

The Wood Island Lifesaving Station, which predated the founding of the U.S. Coast Guard, and Whaleback Light perched atop an inhospitable rocky shoal, informally mark the mouth of the river.

Holt pointed out numerous landmarks and their history as the tug made its way toward open water, where the 600-foot New England was about two miles offshore. Holt was joined by Capt. Chip Taccetta, a longtime tugboat captain and apprentice pilot who later brought the ship into berth at the Irving Oil terminal. On this voyage, like most in Portsmouth, Z-One served as both assist tug and pilot transportation.

Winds were calm and seas were two feet with occasional larger swells as Z-One came alongside New England’s starboard side at about five knots. Deck hand Chris Gallagher secured the ladder as both pilots climbed onto the Marshall Islands-flagged ship.

Z-One and Handy Four stayed alongside New England as it chugged into the mouth of the Piscataqua. Handy Four got its line up on starboard bow, while Z-One worked from center lead aft. From there, Reeves stretched the line and primarily operated between the port and starboard corners on the transom, known locally as “working the tips.”

“The transit inbound is what I consider an informal escort,” Reeves explained. “We help the ship steer around the turns by accelerating or decelerating their rate of swing.

“[We] slow the ship by pulling the ship directly astern if they need to slow down [and] use a higher engine bell to steer the ship so they are working against us, effectively getting more performance out their rudder but not going any faster because we are slowing them at the same time,” he continued.

A Maine native, Reeves has worked on tugboats for 14 years. He spent time with ship assist outfits in the Gulf of Mexico, Norfolk, Va., and Portland, Me., over the years. His path to tugboat captain started after graduating from Maine Maritime Academy, where he initially planned to study marine biology.

“But I had friends in this program and liked what they were doing and found it suited me,” Reeves recalled while helping New England up the Piscataqua.

The river narrows as it passes New Castle Island to the west and Seavey’s Island to the east, the latter occupied by the naval shipyard where nuclear submarines are maintained and overhauled. The white façade of the former Portsmouth Naval Prison, considered by some the “Alcatraz of the East” until its closure in 1974, towers over the horizon.

Although Holt joined Taccetta aboard New England, the apprentice pilot had the conn. The pace of his orders to Handy Four and Z-One increased as the ship entered tighter confines around Seavey’s Island. Taccetta’s orders kept the ship’s speed in check and its bow and stern in shape within the channel.

“All stop, Z-One.” Taccetta said over VHF radio as the ship approached Henderson Point on Seavey’s Island. “I’m gonna drag you.”

Taccetta followed that order moments later with another asking Z-One to back at one-third power.

Reeves acknowledged each pilot order with a blast of the tug’s whistle – something Holt picked up working as a tugboat captain in New York City. The custom lets tug captains acknowledge a command while minimizing radio chatter.

Local custom also dictates how pilots request tugs push or pull them within the channel. Instead of saying to the right or left, or port or starboard, pilots use New Hampshire and Maine, located on the left and right sides of the river, as reference points.

“When inbound with a ship in Portsmouth, Maine is on the right side of river, so saying ‘push me to Maine’ or ‘indirect to Maine’” is the same as saying “to the right,” Holt explained. “New Hampshire is to the left and when outbound with a ship, it is the opposite. We’re trying to make it crystal clear right or left by including Maine or New Hampshire as a reference,” he continued.

Over the next 15 minutes, Taccetta relied on Z-One and Handy Four to navigate through the two lift bridges bookending a dogleg turn just upriver from downtown Portsmouth. With help from Z-One backing at half power, New England slowed to 1 knot as it approached the Irving Oil terminal, located in the shadow of the Piscataqua River Bridge 135 feet overhead.

Reeves swung the tug around the transom to the starboard quarter to dock the ship. Handy Four, meanwhile, worked from the starboard bow. Brewster, the Handy Four captain, and Reeves followed a series of orders from Taccetta. New England was safely against the Irving Oil dock as the late afternoon sun set.

Taccetta descend New England’s accommodation ladder.

Irving product tankers like New England and its sister ships are regular customers at the Port of Portsmouth. The region averages four to six inbound ships a week in the winter, primarily carrying road salt, gypsum, and refined products such as gasoline, kerosene, or heating oil. Ships carrying asphalt and low-sulfur coal used as standby fuel for nearby power plants are also common throughout the year.

“From being here a while, one of the things I notice is that the bulk ships are a lot bigger than in the past, so there are less of them,” Holt said.

Moran employs nine mariners in Portsmouth, enough to crew three tugs with a captain, deckhand, and engineer. Crews work a week followed by a week in on-call status. The schedule works for Gallagher, who joined Moran after working on lobster boats and later tugboats in Boston Harbor.

Gallagher is building his license and hopes to become a captain. “I like working on the water,” he said as linesmen secured New England to the dock. “And Moran is a really professional company to work for.”

For Reeves, working in Portsmouth offers the chance to stay close to home after working in bigger ports a plane ride away. Scenery along the Maine and New Hampshire Seacoast is a bonus, along with the friendly feel operating in a tourist town, where people are continually fascinated by working tugboats.

He also appreciates the culture at Moran – a sentiment routinely echoed by Moran mariners at other ports. “There is another level of professionalism here,” Reeves said. “And it feels like they are looking out for their best interest as well as yours.”

Holt, he added, has a well-earned reputation as one of the best managers in the industry.

prepares to throw a heaving line from the Z-One’s aft deck.

The lines secure, Gallagher helped Holt and Taccetta climb back onto Z-One. The three joined Reeves in the wheelhouse for the return to Tugboat Alley a half-mile downriver.

“Pretty work, Chippah,” Reeves said to Taccetta, pronouncing his name with an exaggerated Downeast accent. “Bringing in a loaded one, not bad.”

Taccetta, who is in the third year of his five-year apprenticeship, estimates he has worked more than 200 ships during that time. “Every trip I do, I get a little more comfortable,” he said. “It’s nice when we gave these smaller tides and we have a little more time to do it.”

A former tugboat captain, Taccetta made sure to recognize the role each vessel played in a successful docking. “Z-One and Handy Four make it all possible.” •