Maritime vessel operators need to be aware of new and heightened concerns about how offshore wind (OSW) towers can interfere with and degrade radar systems. Mariners can be impacted on at least two fronts, one being interference with marine vessel radar.

According to a report released earlier this year by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), wind towers undercut a radar’s central purpose: safety. The steel towers can distort information about a vessel’s relative location, a degradation that affects all vessel classes.

Turbine blades clutter a radar’s display, resulting in an ambiguous and confusing picture for the operator. Correcting for these effects may make smaller vessels “disappear” completely.

The other impact is interference with high-frequency radar (HFR) systems. These systems measure the speed and direction of ocean surface currents in near real time and are at the core of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) ocean observation system and the advisories NOAA prepares regarding ocean and weather conditions.

The network includes more than 140 HFRs. Offshore wind turbine interference can cause blind spots in this national network. No other system can measure and detail large ocean areas at once. Coast Guard search and rescue depends on HFR, and it is central for navigation and oil spill response at California’s largest ports. HFR degradation has consequences for ships at sea, port operations and coastal communities.

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report, titled “Wind Turbine Generator Impacts to Marine Vessel Radar,” was released in February and is the work of an expert committee commissioned in 2021 by the Bureau of Energy Management.

The study states that the size and scale of planned offshore wind projects are central factors responsible for radar interference and degraded performance.

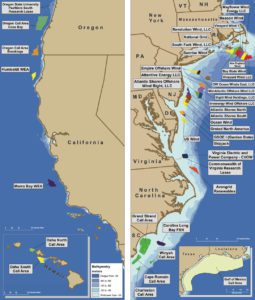

The hub height for wind towers is projected to increase from 330 feet to 500 feet, while blade lengths are to exceed 300 feet. The U.S. goal is to generate 30 gigawatts (GW) of energy from offshore wind by 2030. The size of each singular tower and the cumulative impact of thousands of such towers set among vast wind-energy areas presents a physical mass impossible for radar signals to miss.

In a recent interview, committee chair William Melvin highlighted this type of project scale. When asked if he had an “Aha!” moment as the committee’s conclusions emerged, he said: “Yes. What struck me is the scale of what is being proposed.”

Melvin estimated that a 30-GW generating capacity could require 5,000 wind towers. For perspective, Melvin said that “the radar signal of a single wind turbine presents as the signal from a supertanker or an aircraft carrier. Imagine you are traversing the ocean and you have 5,000 aircraft carriers. That is the sense of strength of the returns coming back.”

The National Academy of Sciences wrote that the highly conductive steel towers cause “aspect-independent radar reflections.” Signal returns from the turbine blades are “aspect-dependent and can appear even larger than reflections from the tower for certain geometries.” Blade composition, construction and orientation also affect how severely a vessel operator’s display is skewed. Additionally, a vessel’s own radar can make the problem worse because it can accentuate “multipath reflections” from the ship’s superstructure that mix with the wind-tower returns, further distorting an operator’s information.

Importantly, the new academy analysis is U.S.-focused. Previous radar/wind turbine studies relied on European wind farm data. But the academy explains that plans for U.S. offshore wind require larger equipment, across spatially larger wind-energy areas and in configurations different from the European model.

Impacts from floating wind farms — in the planning stages now for the Pacific — may pose additional challenges. The wave-induced motion of floating towers, the science academy wrote, “will likely provide a less-consistent radar return overall and may also increase clutter and complicate Doppler return interpretation.”

The 96-page report presents two broad conclusions and follows up with a number of related recommendations. The conclusions:

• “Wind turbines in the maritime environment affect marine vessel radar in a situation-dependent manner, with the most common impact being a substantial increase in strong, reflected energy cluttering the operator’s display, leading to complications in navigation decision-making.”

• “Opportunities exist to ameliorate wind turbine generator-induced interference on marine vessel radars using both active and passive means, such as improved radar signal processing and display logic or signature-enhancing reflectors on small vessels to minimize lost contacts.”

Melvin noted that the 2030 goal is eight years out. As such, there is still time to do the research and development and get good answers and harmonize our need for renewable energy with increased confidence in marine navigation safety,” he said.

The NAS report recommends near-term, mid-term and long-range mitigations. Near-term solutions could include revised operator training and placing reflectors on certain vessels to increase visibility. Longer-term efforts might include new radar technologies and software, along with new and different materials for towers and blades.

NOAA’s high-frequency radar concerns

Krisa Arzayus, deputy director of NOAA’s Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS), and the designated federal official for the system’s advisory committee, said via email that interference from wind towers “can have serious degradation on the performance of these radar systems” and added that “our program is actively involved in working with wind energy developers and (the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM) to mitigate the interference with our high-frequency radars.”

Brian Zelenke, Surface Currents Program Manager with IOOS, was asked about resolving these radar/wind tower conflicts. So far, interference problems “have not proven easy to solve.” He noted that “considerable work has already been conducted in search of solutions.”

The federal government has a long-standing work group focused on radar interference called the Wind Turbine Radar Interference Mitigation (WTRIM) working group. It was established in 2014 and includes participants from numerous agencies. Radar interference from wind towers is not a new issue, but its early focus was on aircraft radar and land-based wind towers. New and different concerns arose as offshore wind advanced, particularly at a disproportionately larger scale.

According to Zelenke, new long-term R&D programs will be required to “make and keep mitigation methods operational.” In addition, he said that as offshore wind farms and turbine technology continue to evolve, those developments will require concurrent efforts to ensure that mitigation measures remain effective.

He said that IOOS, with BOEM and wind developers, has made progress on preliminary mitigations that will be tested, but only after large-scale wind farms are installed.

NOAA has awarded a three-year, $1.2 million grant to develop software tools to mitigate wind turbine interference, with the work being led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. This is to build on previous research funded by BOEM and detailed in a report from 2018.

BOEM has indicated that “it is vital to develop mitigation software for the U.S. national HFR network before much larger offshore wind farms are constructed” and that mitigation software will become increasingly “necessary to preserve the integrity of the national network of coastal HF radars.”