While it’s still possible to get a good-paying job in the maritime industry with only a high school education, long-term career prospects are much better with some secondary education.

That was a takeaway from the most recent maritime workforce analysis commissioned by the state of Louisiana, which serves as home to more than 20 percent of the nation’s maritime workforce and whose mix of coastal ports and position at the mouth of the Mississippi River inland waterway network make for a microcosm of the industry as a whole.

According to the 2020 report, 54 percent of maritime industry job postings required only a high school diploma. But over the past 10 years, there was a slight dip in jobs needing little or no skills or prior experience and an increase in demand for “middle-skill occupations that were enhanced with some college education, a high-school diploma with an apprenticeship or moderate to long-term on-the-job training.”

The report concludes “that middle-skill workers who obtain higher degrees and certifications may be more insulated from job losses in the future.”

Industry apprenticeship programs, community colleges and other associate degree and certificate-granting institutions across the country have long promised that, that in addition to training for the necessary U.S. Coast Guard certifications, there is a growing demand for the courses they offer and the skills they teach as new and experienced mariners seek ways to improve their skillset and boost their job prospects.

The junior college pipeline

Most students who enter community and technical colleges to pursue maritime careers recently left either high school or the military, said Capt. Randy Savoie, marine instructor at Northshore Technical Community College in Hammond, La.

The Marine Technology Program at Northshore has tried to recruit students through job fair and connections to nearby high schools (and even junior highs). “Students often bring some experience,” he said.

“Of course, here in Louisiana, the Bayou country, with the bayous and canals, a lot of times we get students that are the outdoors type, people that like being on the water, fishing and hunting and stuff like that,” said Savoie, adding that many of the classes are offered in the evening to accommodate students with day jobs.

Savoie has 35 years of teaching experience with maritime schools in Louisiana’s technical college system and has been teaching at Northshore’s Maritime Technology Program for the past five years.

With seafaring and riverboat jobs so plentiful in Louisiana, many have relatives who have worked on vessels.

As for ex-military students, many use their G.I. Bill options to enter a field that requires a similar skillset and mentality.

According to John Nappo, director of the Office of Maritime Technology at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, NY, most of his program’s students also come from local high schools and the military, but it’s a more of challenge to reach students in New York City.

“We have to find our students and convince them that there is a way to make a living in a field they’ve probably never heard of before,” said Nappo. “I think that’s been the biggest challenge for Kingsborough in the 35 years that the program has been open.”

The school tries to maintain strong relationships with city high schools and advertises its credo that “even people who weren’t great students in high school may make good mariners.”

Greg Wisener, manager of the Waterfront Campus of Southern California’s Orange Coast College, told Professional Mariner that the facility “is an excellent place for anyone to have a great time while learning on the water.”

Wisener said he “is proud of the enthusiastic faculty, staff, and instructors who engage people of all ages, backgrounds, and experience through several hands-on learning programs.

Dozens of students enrolled in the college participate in the Professional Mariner Academic Program, earning college credit towards certificates or an Associate degree, and completing Coast Guard-approved courses in which they earn certifications needed for their Merchant Mariner Credentials.

Many other students “compete in inter-collegiate athletic rowing as members of the Orange Coast College women’s or men’s crew teams. Thousands of people who aren’t academic students take community classes to learn to sail, powerboat, navigate, and develop other skills through the School of Sailing and Seamanship, while experienced professional mariners attend career advancement classes to enhance their skills while earning certifications towards licensing and endorsements,” he said.

“The unifying purpose of this place is to provide affordable, equitable access to all people so they can learn and grow,” he said. “We want to encourage people to explore their curiosity and learn about boats and the sea in a way that’s going to add value to their lives. We want people from all communities to know they are welcome here. We want to make it possible for people with limited resources to take a class and get out on the water.”

Education beyond certification

Education beyond certification

Obtaining Coast Guard certification for specialized skillsets like bridge management or security duties or just able seaman designation, is often the underlying goal for students at these programs, and many have components that will get students on vessels to earn requisite sea time.

“There’s kind of two levels of building a mariner,” said Wisener, “and one is making sure that they understand their craft and the other one is making sure they have all the certificates they need to actually get employed.”

In order to entice students away from the cheaper and easier option of applying for a job that only requires a high school diploma, many programs design a comprehensive curriculum that will make graduates more attractive to potential employers or suited for higher-level positions.

According to Savoie of Northshore Technical, in addition to seamanship, the school curriculum includes radar and electrical systems, first aid, hydraulics, and welding, among other skills. The program also includes leadership classes with elements of behavioral psychology, including lessons on managing individuals with a history of addiction.

The two-year program offers a Certificate of Technical Studies in General Marine Transportation Technology, a Technical Diploma in Maritime Technology, or an Associate degree in applied science in Maritime Technology.

“All these subjects that are in the program are things that would take years for a person who’s just starting out straight out of high school, going straight on a boat without any experience whatsoever to learn,” he said.

Kingsborough Community College has built entryways for further education. “Generally, we can put people into a place like SUNY [State University of New York] Maritime,” said Nappo.

The school can also send graduates directly into a program with the Seafarers International Union. After some specialized training at a union facility in Maryland, “they’re guaranteed a job to go ship out immediately at $7,000 a month. After two years of training, that’s not bad,” said Nappo.

Wisener, of Orange Coast College, said that curricula and class offerings are based on the school’s relationships with employers, “understanding what they need, and then connecting our students with it.”

In addition to acquiring skills, he emphasized the importance of “getting on the water and getting a feel for the work. If you get them out on the water and they just find their passion and they realize, ‘This is this is what I want to do; this is part of who I am,’ and then they’re a good fit.”

The role of new learning technologies

Today, maritime degree and certificate programs routinely familiarize students with new technologies that not only impact how they can professionally and safely do their jobs while at sea, but expand their horizons into new areas, as well.

For many, this has meant an emphasis on offshore wind. A blitz of leasing and construction activity off the East Coast has made it the most buzzed-about sector of the industry, as navigating in towering, forest-like stands of wind turbines offer unique challenges to mariners.

In response, Kingsborough Community College has set the goal of launching a “global wind organization” training program in the fall of 2024 to instruct students in the particular navigational and safety concerns involved in working among offshore windfarms.

The program is being funded through a $1.5 million grant from the New York City Council.

“In the Gulf, there is a very heavy presence in oil and gas,” said Kingsborough’s John Nappo. “We don’t have that here, so people up in the Northeast are really going wholeheartedly into promoting wind energy.”

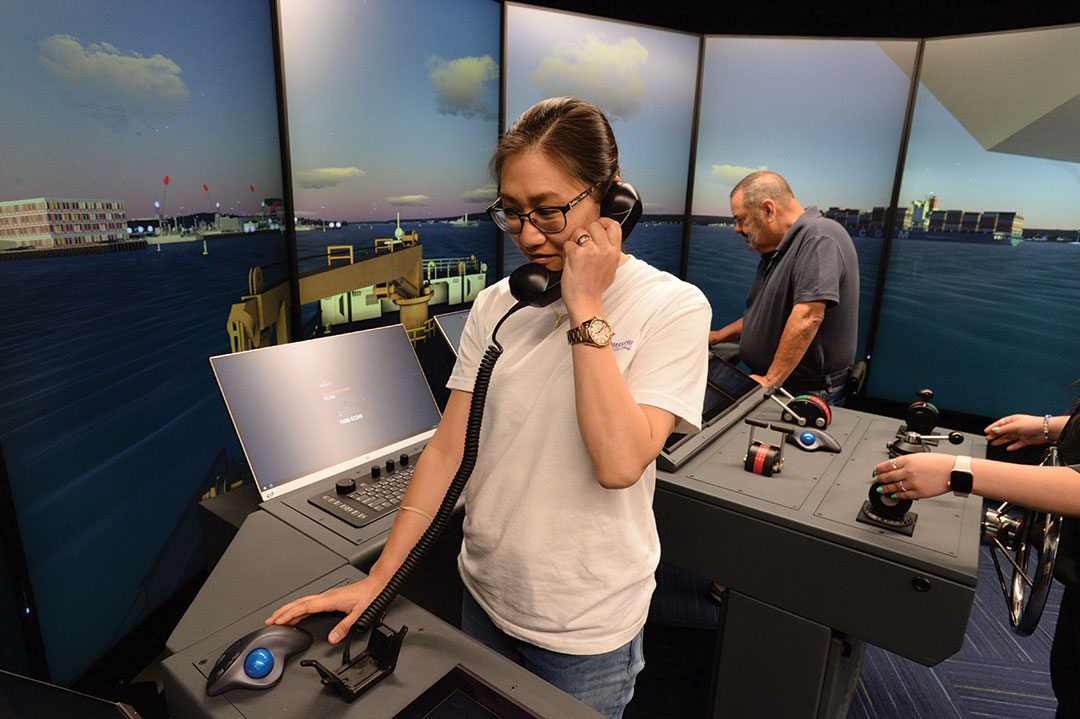

In California, Orange Coast College also has invested in training students for offshore wind work, programming its computer simulators with software used for bad weather, while also offering possible collision scenarios to teach the skills needed to safely navigate through offshore windfarms.

By simulated learning, “They can see the different conditions and currents, and how they would maneuver around the different wind turbines,” said John Vicente, a maritime lab simulation technician.

Another area of growing interest is the use of autonomous vessels.

Despite the fact that such unmanned vessels – which are often used for data gathering in hazardous conditions – there is, and always will be, a need for ultimate human control and oversight of the vessels navigation and onboard operations – a person ‘at the helm,’ so to speak.

The demand for workers well-versed in that burgeoning technology was the impetus for a five-week program at the University of Southern Mississippi’s Gulf Coast (USMGC) campus on operating autonomous vessels.

The program’s training curriculum was developed in partnership with the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Navy’s Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command, which oversees the development and testing of the Navy’s unmanned subsurface vessel program.

“Typically, our base is students who already have jobs, so mostly federal government,” according to Carl Szczechowski, an oceanography instructor and coordinator of the USMGC program.

“Many of our students are employed by the U.S. Navy and range in background from a 60-something with a doctorate to a 19-year-old with an Associate’s degree.”

Uncrewed vessels are “revolutionized every few years,” as power sources and guidance systems change, he said.

“There wasn’t a whole lot of this stuff going on until the ‘80s. That’s how recent these new technologies and autonomous systems are. And more and more, they’re getting bigger and bigger and more capable.

“These kinds of courses are going to be more and more necessary because the technology is just extraordinary,” said Szczechowski.

NOAA currently uses autonomous submersibles for seafloor and habitat mapping, ocean exploration, marine mammal and fishery stock assessments, emergency response, and at-sea observations that improve forecasting of extreme events, such as hurricanes, harmful algal blooms and hypoxia.

“Mississippi is poised to become a major hub for ocean research and innovation, and NOAA plans to help drive that innovation,” said Rear Adm. Nancy Hann, deputy director for operations for NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations.

“This new partnership with the University of Southern Mississippi will greatly enhance our ability to transition these technologies into operational platforms that will gather critical environmental data for the nation.”