The captain of the drillship Valaris DS-16 awoke on a blustery late winter night to the sound of a mooring line parting. Others snapped in rapid succession as strong winds pushed the vessel away from the dock at Halter Marine in Pascagoula, Miss.

For the next 20 minutes, the 752-foot Marshall Islands-flagged ship drifted across Bayou Casotte channel toward the Chevron refinery dock occupied by the bulker Akti. The drillship’s crew dropped both anchors and assist tugs arrived in short order, but its stern hit Akti’s starboard side.

Nobody was hurt in the incident, which happened at about 0040 on March 12, 2022, and there was no pollution. Total damage to both ships approached $5 million, according to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB).

Investigators determined Valaris broke free after forwardmost mooring bollard used in the mooring arrangement broke away. That bollard, known as bollard No. 6, and others on the dock, had been modified in ways that made it more susceptible to failure.

“The bollard pipes’ overall height increased from just over 2 feet to anywhere from about 4 to 7 feet — about 2 to 5 feet higher than originally designed,” the NTSB said in its report, noting that the extra height placed additional stress on the bollard’s base.

“Therefore, bollard 6 — and many of the other bollards used to secure Valaris DS-16’s mooring lines — were likely incapable of sustaining the working loads of their original design,” the report continued.

Valaris DS-16 arrived at Halter Marine on Jan. 26, 2022, after a layup in Spain. Workers at the Mississippi shipyard were reactivating the ship to return to service in the oil production trade when the incident occurred. The ship’s six thrusters were recessed into the hull due to water depths at Halter’s dock, leaving it without propulsion.

Valaris’ operating company, Ensco International, developed a mooring plan with input from Halter Marine. The operator requested details on the mooring locations and strengths of the 14 bollards at the facility. According to the report, the bollards ranged from 52 to 84 inches high.

The shipyard did not have pull test ratings for each bollard. But it provided evidence from a tugboat bollard pull test indicating at least one bollard in the yard could withstand 154 metric tons. It did not say which one had that capacity. Each bollard was painted with markings showing “300T” — suggesting a safe working load of 300 tons.

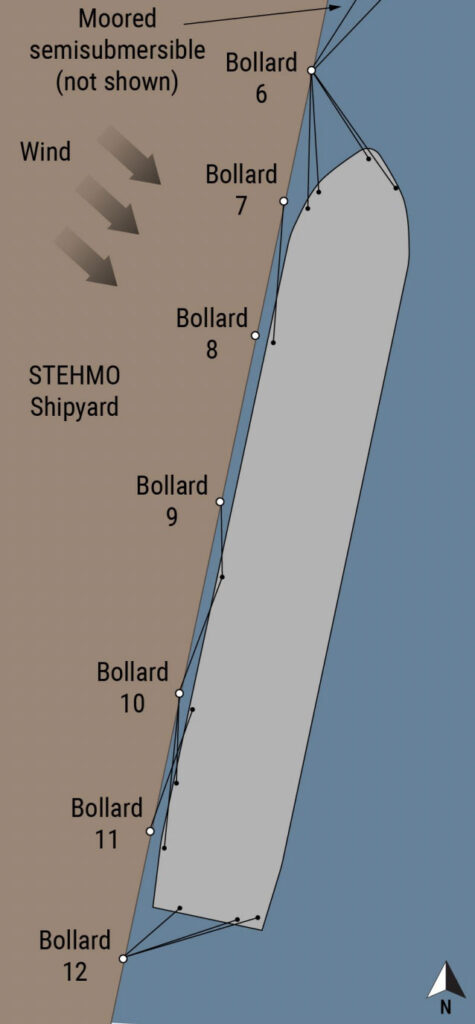

Valaris’ operator developed a mooring plan that its captain modified to better protect against winds from the west, which would have pushed the ship away from the dock. The arrangement used four lines on the bow from bollard 6, six lines amidship to bollards 9, 10 and 11 and three lines connecting the stern to bollard 12, the NTSB said.

The ship’s captain, who was not identified, received a weather report at about 1800 on March 11 warning of strong winds starting after midnight. The captain relocated a mooring line forward to bollard no. 7 to reinforce the bow. The chief mate also trained the crew on dropping anchor in an emergency.

“Deckhands were instructed to check the mooring lines every hour from the dock, and, as the winds increased, to remain on the dock to monitor how the lines were being loaded,” the report said. “About 2300, the weather frontal system began passing through the area with 30-knot northwest sustained winds from the direction of 312 degrees.”

Wind sensors on the ship located roughly 300 feet above the waterline showed gusts reached up to 51 knots shortly after midnight. The NTSB estimated winds were between 30 and 40 knots against the ship’s hull. Based on the mooring analysis, investigators said the arrangement should have been sufficient to secure the vessel to the dock in those conditions.

The captain awoke at about 0020 to the sound of lines parting and a shuddering sensation from the ship. He reached the bridge soon afterward and learned bollard No. 6 had broken free, leaving its bow untethered to the dock. Remaining lines parted as winds pushed against the vessel from the northwest.

Deck crewmembers let go the port anchor at 0025, and it caught on the bottom about 10 minutes later. Soon afterward they let go the starboard anchor, which caught quickly. Both anchors slowed the ship but did not stop it. Assist tugboats arrived before the collision but could not completely control the massive vessel’s stern.

Valaris’ captain warned crew aboard the Marshall Islands-flagged bulker Akti of the impending collision. Soon afterward, at about 0041, Valaris’ starboard side made contact with Akti’s starboard side. The drillship sustained roughly $4.2 million in damage, while Akti needed about $800,000 in repairs. The Chevron dock was not damaged.

Federal investigators homed in on the bollards at Halter’s facility, which had undergone modifications before the yard’s owner at the time, ST Engineering, bought the facility. Investigators also found wastage and damage along the base of several bollards.

“There were no records of these modifications,” the NTSB said. “There were no policies or procedures addressing the frequency of inspections for the shipyard’s bollards, nor were there any statutory requirements for inspections.”

The drillship remained alongside Akti until later in the day on March 12 and returned to the Halter Marine dock that afternoon. Since the incident, at least ten of the 14 bollards have been replaced. Bollinger Shipyards acquired Halter Marine last fall. It is continuing the bollard replacement that began last year.