Capt. Aaron Sheridan steered Capt. Richard G. Spear through Rockland Harbor on a picture-perfect summer day in Maine. Clear skies and calm seas lay ahead as the Maine State Ferry Service’s newest vessel chugged toward Vinalhaven some 15 miles away.

Every so often, Sheridan nudged the 154-foot ferry to port or to starboard. With each subtle course change, he avoided colorful lobster fishing equipment known as pot buoys (rhymes with “boys” in local vernacular) floating on the surface.

“It’s starting to come into lobstering season around here,” said Sheridan, a 10-year captain with the Maine State Ferry and a former lobsterman himself.

“Rockland has a short season and they have only so much area to fish, so this is where they are,” he said of the lobster traps’ proximity to the ferry route. “They leave a little break for us, but not much. If there are no boats around and it’s not foggy, I do my best to dodge the gear.”

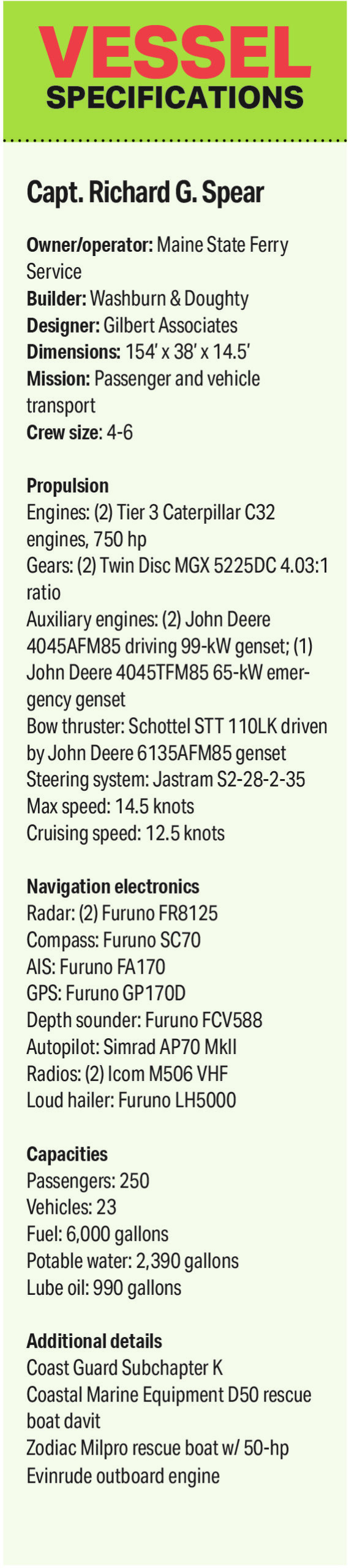

Washburn & Doughty, located about an hour away in East Boothbay, Maine, built the 23-car Capt. Richard G. Spear using a design from Gilbert Associates of Braintree, Mass. The vessel is named for a legendary Maine mariner who went on to lead the state’s ferry service for 30 years until his retirement in 1989. A Rockland native, Spear was a 1943 graduate of Maine Maritime Academy who served in the U.S. merchant marine during World War II. He later earned an unlimited master’s license, for ships of any size and tonnage in any ocean, according to state ferry officials. Spear died in May 2018 at age 96.

Spear was the first full-time employee hired by the newly established Maine State Ferry Service in 1959. These days, the service operates seven ferries serving six routes, most of them connecting islands in and around Penobscot Bay with the mainland. In 2019, the last full year before the Covid-19 pandemic, Maine State Ferry vessels carried nearly 453,000 people and 170,000 vehicles.

The Rockland-to-Vinalhaven route is among the busiest and most spectacular. Within 20 minutes of departing Rockland, the 1,500-hp Capt. Richard G. Spear passed the 120-year-old Rockland Breakwater Lighthouse, positioned at the end of a stone wall extending nearly a mile into the harbor, and the stately Owls Head Lighthouse perched atop a rocky bluff.

The horizon looking east toward Vinalhaven was dotted with sailboats and lobster boats. Looking west, Rockland Harbor and the blue-green Camden Hills dominated the skyline. Colorful lobster pot buoys dotted the waterline in almost every direction.

“The view is one of the things I like best about working out here,” said AB Hannah Harm, who joined the ferry service almost two years ago after graduating from Massachusetts Maritime Academy. “It’s a pretty good office.”

Capt. Richard G. Spear would normally operate with a five-person crew consisting of a captain, chief engineer, two ABs and an ordinary seaman. Staff shortages that have hit just about every industry also have impacted the Maine State Ferry Service, and the vessel is currently running with four crewmembers. The ABs each steer for at least one run each day during normal operations.

The ferry system runs two boats between Vinalhaven and Rockland, with one starting the day at each terminal. The state provides housing on Vinalhaven for the Spear crew, which operates from the island. Typical rotations consist of seven 12-hour days followed by a week off.

Rockland-Vinalhaven ferry captains have historically come from the island, which has a proud maritime tradition. Vinalhaven, with a year-round population of about 1,300, is home to a large lobster fishing fleet. Sheridan grew up on the island, and Jack Olson, Spear’s chief engineer, still lives there. Olson joined the ferry system after a career catching lobsters.

Sheridan started fishing for lobsters as a teenager and he spent 14 seasons in the trade. He readily admits he wasn’t much good at it. “I decided to get a real job,” he said with a half-smile.

Indeed, lobster fishing is difficult work, and successful fishermen hone their trade through years of experience. “You’ll get some guys who set their traps in the same bottom or same deep hole, and they haul their traps out and get one while the other guy gets 10,” Sheridan said. “It all depends on how you bait your gear, and there is some luck involved. Some guys can think what the lobster is going to do before they even do it.”

After passing Owls Head, the vessel plied the open waters of Penobscot Bay, where it met the eastbound ferry Capt. Charles Philbrook roughly halfway between Rockland and Vinalhaven. Philbrook’s captain on this afternoon was Capt. Bill Dickey, who happens to be Sheridan’s father-in-law. Capt. Richard G. Spear, which can exceed 12.5 knots, made about 11 to reduce fuel consumption during a time of record fuel prices.

Winds and seas were calm on this early summer afternoon, but Penobscot Bay can be unforgiving. Fog is a year-round concern, and storms can send the ferry’s bow diving into the surf in all four seasons. Strong winds are the primary reason any sailing gets canceled, Harm explained.

“We’re only out here (in open water) for 15 or 20 minutes, but that can be a long 15 or 20 minutes on some trips,” she said. “Especially if it’s foggy and dark. You are just picking your way through the waves.”

The approach into Vinalhaven can be tricky even on calm days. The island is surrounded by countless small islands, ledges and reefs, many of which are hidden during high tide. The ferry route passes through Lawrys Narrows west of the island before doglegging to the southeast through Hurricane Sound, known locally as the Red Sea. Finally, the route passes through an area known as The Reach, which is barely 150 feet wide at its narrowest point.

“It is a lot of zigzagging,” Sheridan said as he steered through the craggy waters. “But picture this (in the fog) and not being able to see 20 feet in front of the bow and other boats coming at you.”

Like many seasoned captains, Sheridan uses landmarks to guide his approach into the island. When entering Hurricane Sound, for instance, he aligns the bow with the eastern tip of Leadbetter Island. Radar also helps. He sets the vessel’s twin Furuno radars at a quarter-mile and half-mile range for this section of the voyage.

engineer Jack Olson stands alongside a Caterpillar main engine.

The propulsion system on Capt. Richard G. Spear consists of two Caterpillar C32 engines driving conventional propellers through Twin Disc gears. Two John Deere auxiliary engines supplied by R.A. Mitchell Co. generate electrical power. A third John Deere engine paired with a larger genset supplies electrical power to a Schottel bow thruster.

Vinalhaven Harbor, home to dozens of brightly colored lobster boats, finally comes into view during the last few minutes of the 80-minute ride. Sheridan slowed for the final approach and nudged the bow into position against the terminal. Within 90 seconds, Harm and her fellow AB Josh Morehouse began directing vehicles off the ferry.

Harm and Morehouse, whose father is the captain of another Maine State Ferry vessel, have the loading down to a science. They get help organizing the vehicle queue from ferry personnel based on the island.

“Hannah, she’s smart and knows how to take control of the deck and figure things out,” Sheridan said.

After about 45 minutes at the Vinalhaven terminal, 22 vehicles were safely aboard for the return trip. About 75 passengers came on as well, including a Little League team from the island competing on the mainland. Two of the larger local lobster boats would bring the team back later that evening, after the ferries had tied up for the day.

Sheridan, a former Vinalhaven resident, knows the importance of the ferry. Running behind means passengers miss appointments or show up late for work. Likewise, Capt. Richard G. Spear can fit six more vehicles than its predecessor. That means fewer residents get stranded on the mainland for the night. Most vehicle slots on the boat are available first-come, first-served, and space is not guaranteed.

Sheridan, a former Vinalhaven resident, knows the importance of the ferry. Running behind means passengers miss appointments or show up late for work. Likewise, Capt. Richard G. Spear can fit six more vehicles than its predecessor. That means fewer residents get stranded on the mainland for the night. Most vehicle slots on the boat are available first-come, first-served, and space is not guaranteed.

Sheridan got underway for the return voyage by backing off the dock and spinning counterclockwise 90 degrees, putting the bow to the southwest. He took the same path back to the mainland as he took coming out, snaking between narrows and avoiding ledges lurking five or six feet below the keel.

The ferry encountered a handful of lobster boats along the way. Sheridan knew the owner of each boat and greeted each captain with a wave. While passing through Hurricane Sound, he pointed out a lobster boat owned by the chief engineer’s son.

Tourists who walked to the end of Rockland Breakwater Lighthouse waved as the ferry passed. Minutes later, Sheridan slowed for the S-turn into the Rockland terminal. He inched toward the landing and then spun the vessel 180 degrees to arrive stern-first.

And so continued the loading and unloading of vehicles and people, providing a lifeline to Maine’s island communities. •