A cargo ship that dragged anchor in the fast-moving Mississippi River struck another ship, then careened into a chemical dock near New Orleans.

The incident involving the 453-foot Nomadic Milde happened on May 8, 2020, at 1655 near mile 114.5 after the ship dragged anchor in a 4.5-knot current. The ship first hit the 590-foot Atlantic Venus just downriver and then drifted into the nearby Cornerstone Chemical dock. No one was injured and pollution was minimal, but the incident caused $16.9 million in property damage.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators determined inattention by the bridge crew aboard the Marshall Islands-flagged Nomadic Milde was a leading factor in the incident.

“The Nomadic Milde’s positions and headings suggested that the Nomadic Milde did not initially settle at its original anchor position,” the NTSB said in its report.

“There was no evidence of either watch officer checking the ship’s position at frequent intervals or by means other than the ECDIS watch alarm to determine if the ship was secure at anchor or not,” the report added, referring to its electronic chart display and information system.

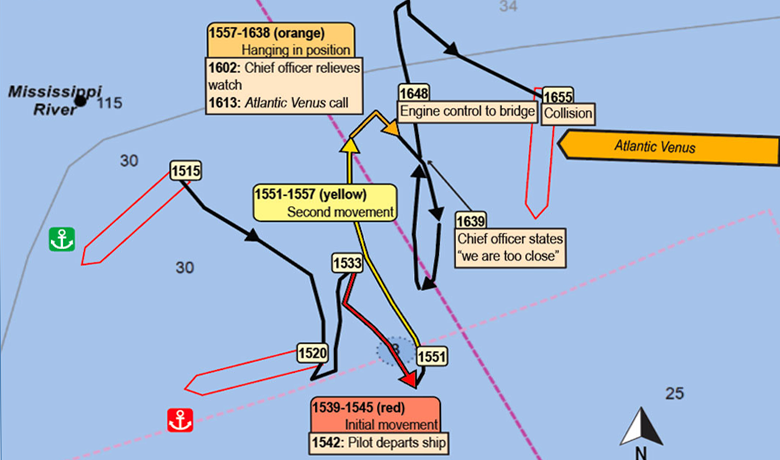

On May 8, Nomadic Milde loaded lead concentrate from a terminal at mile 107.6. The ship got underway at 1350 for the Kenner Bend Anchorage about 8 miles upriver to repair a cargo hatch. The New Orleans-Baton Rouge Steamship Pilots Association (NOBRA) pilot at the conn guided the ship between two anchored bulkers. The Panama-flagged Atlantic Venus was located about 500 feet downriver from Nomadic Milde’s initial position.

Nomadic Milde’s bosun oversaw the anchoring maneuver, which paid out 360 feet of chain on the starboard anchor and 270 feet on the port anchor. “At 1532,” the report said, “the bosun on the bow informed the bridge that the starboard chain was leading 12 o’clock with a short stay and the port chain was leading 9 o’clock with a long stay.”

Based on that report, the NOBRA pilot indicated the anchoring was finished and the ship was secure. The pilot, who was not identified, encouraged the master to keep the engine on a short standby given the strong current and possibility of bad weather. The master heeded the suggestion, and at 1542 the pilot left the ship.

According to the NTSB, the ship was still moving when the pilot disembarked. Neither the pilot nor the bridge team recognized it at the time. Later, the pilot said he had no concerns about the ship’s anchors holding when he disembarked.

The master left the bridge soon after the pilot. The second officer, who stood watch on the bridge until 1600, set the anchor watch alarm on the ECDIS to sound if the ship moved more than 590 feet — even though just 490 feet separated his ship from Atlantic Venus.

The chief officer who relieved the second mate at about 1600 had just joined the ship and was standing his first watch. He recognized on ECDIS that the ship had moved within the anchoring radius but acknowledged to the second mate he was unfamiliar with the system. Neither mariner addressed the ship’s position at anchor again.

At 1613, the second mate aboard Atlantic Venus called Nomadic Milde over radio urging the ship to monitor its position. The chief mate on Nomadic Milde acknowledged the call and said its engine was on short notice to respond as needed. Over the next 20 or so minutes, Nomadic Milde mostly held steady. But at 1639, the chief officer recognized it had shifted too close to Atlantic Venus.

The chief officer alerted the ship’s master at about 1645. The master contacted Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) in New Orleans. The VTS supervisor warned him not to raise anchors without a pilot, but none were immediately available.

The chief engineer prepared the main engine and transferred control to the bridge. The master ordered the engine full ahead and activated the bow thruster and rudder to counter the ship’s movement toward Atlantic Venus. The actions were not enough to prevent the impact.

Nomadic Milde’s port side struck Atlantic Venus’ bulbous bow and anchor chains and stayed in contact. As the current pushed on Nomadic Milde’s broadside, both vessels moved toward the right descending bank toward the Cornerstone Chemical dock.

Notified of the accident, VTS called for tugs to assist. The first arrived at about 1725 to help hold Nomadic Milde in position. About 30 minutes later, NOBRA “rush” pilots boarded each ship.

The first tractor tug arrived at 1854 and took position on Nomadic Milde’s port bow. The pilot on the ship issued a series of orders intended to steer clear of the Cornerstone Chemical dock, but Nomadic Milde remained unresponsive in the current. Ultimately, the ship’s bow hit an upriver section of the dock at 1858, causing almost $11 million in damage.

Nomadic Milde required about $5.5 million in repairs, primarily to its hull and propeller. Atlantic Venus sustained $410,000 in damage. Pollution was limited to about 13 gallons of lube oil.

Investigators determined the bridge team aboard Nomadic Milde had ample opportunity to recognize and respond to the unfolding situation. However, they erred by relying solely on ECDIS to monitor their position rather than cross-checking it with radar.

The chief officer’s failure to warn the master in a timely manner also limited what could be done to prevent the impact with Atlantic Venus, the report said. Additionally, the VTS official’s direction not to heave anchor and instead to maneuver with their engine limited the master’s ability to effectively respond.

“There was sufficient evidence to alert the bridge team that the Nomadic Milde was not holding well,” the report said, “and, had this been detected, the master could have been alerted earlier, and, in turn, there would have been sufficient time to undertake necessary measures to address the problem.”

There are no existing regulations that prohibit a master from getting underway without a pilot during an emergency. However, the VTS watch supervisor admitted his request not to raise anchors likely came across as an order.

Attempts to reach the owner and manager of both ships were not successful.