Climate researchers working for NASA have determined the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) 2020 sulfur fuel cap has succeeded in cutting pollution from ocean shipping. But it isn’t all good news.

A team of scientists led by Tianle Yuan determined lower sulfur content in heavy maritime fuels reduced and sometimes eliminated entirely a cloud phenomenon known as ship tracks.

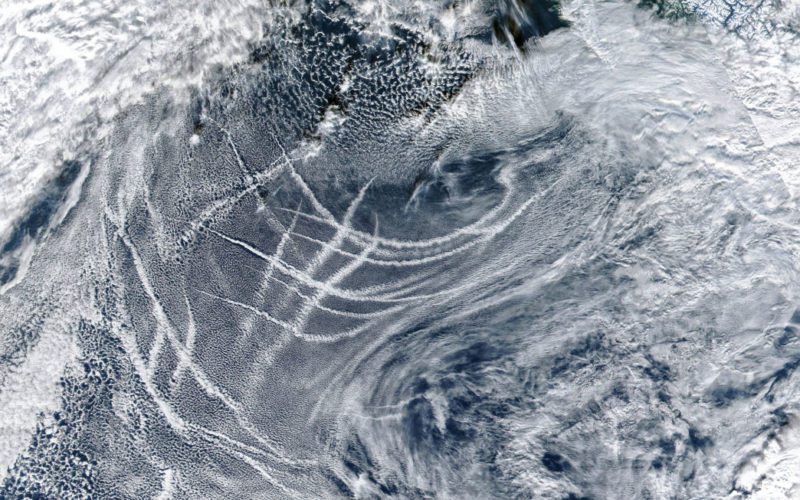

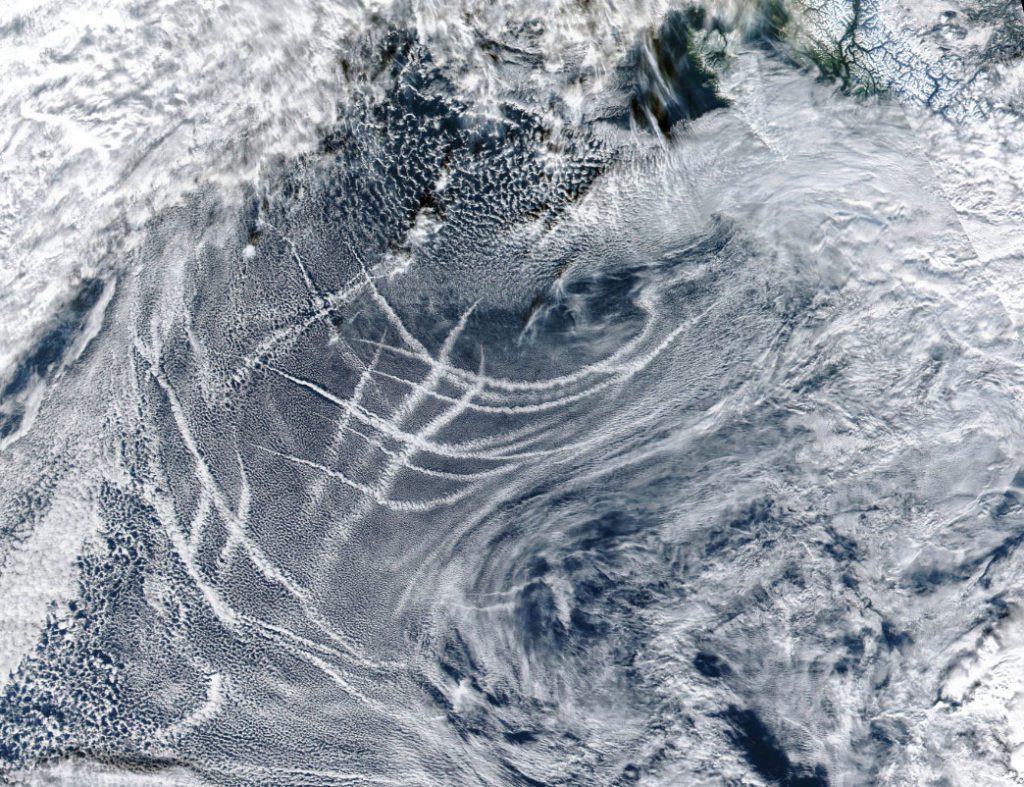

Ship tracks are low-level clouds that can form in the sky and follow a ship sailing from one place to another. These so-called anomalous clouds perform a surprising function: Like other clouds, they reflect the sun’s energy away from the Earth, thereby helping to cool the planet.

Less sulfur in fuel means better air quality, particularly in coastal areas near shipping lanes and ports. But fewer ship tracks could therefore contribute to global warming. By how much is unknown, according to Yuan, a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and a NASA scientist.

“In terms of climate change and the Earth’s temperature, we will have some temporary warming effect,” he told Professional Mariner. “The trouble is we don’t exactly know how much of a warming effect.”

Yuan and nine other scientists published an article on this phenomenon in July in the journal Science.

Ship tracks form when water vapors in the air coalesce around tiny particles of pollution emitted by ship exhaust, Yuan explained. These long, linear cloud formations reflect more light, thus making them appear brighter than clouds seeded by non-pollution sources such as sea salt.

Scientists first discovered ship tracks in the 1960s when reviewing data from early satellites orbiting the Earth. A couple decades later, researchers figured out that ship tracks are useful for studying clouds and their broader effects on the Earth’s climate.

Studying these relatively small cloud formations over the entire Earth is no easy task. Yuan and his team developed an advanced algorithm to review satellite ship track data across the world between 2003 and 2020. When they reviewed results from 2020, the team noticed a surprising decline in ship track formations in every major shipping lane. They initially theorized the decline stemmed from a drop in global shipping during the Covid-19 pandemic. But that proved incorrect, as global maritime traffic barely changed during that period.

Later, they learned about the IMO regulation capping sulfur content in maritime fuel at .5 percent that took effect in 2020. The rule cut sulfur levels by 86 percent, changing the composition of exhaust leaving the stacks and sharply reducing the volume of sulfur particles that help create ship tracks.

“We didn’t even know the regulation that took effect in 2020 because it was totally unrelated to us and our research,” Yuan said.

“So, in addition to the climate science piece, this itself is interesting because it shows the regulation that changed in 2020 must be working because otherwise, we wouldn’t see that global change in ship tracks all of a sudden,” he added. “And it extends to 2021, too.”

The algorithm identified other interesting changes in trans-Pacific shipping over the years, including reduced ship track activity during the Great Recession starting in 2008 and later in the mid-2010s as China reduced imports of certain commodities.

Perhaps more significantly, the researchers found that earlier regulatory changes around sulfur emissions, such as the establishment of IMO Emission Control Areas on the U.S. West Coast, did not have a similar effect on ship tracks. Ocean carriers, the researchers determined, responded by changing their routing to avoid coastal zones where they are required to burn more expensive ultra-low-sulfur fuels.

An IMO spokeswoman said the agency welcomed the research confirming the success of the 2020 IMO sulfur requirements.

The broader effects of the 2020 fuel regulations are still unknown and likely will be for some time. But much of the world falls outside the emission control areas, meaning reduced sulfur output will lower pollution levels and improve air quality for tens of millions of people living near shipping lanes and ports around the world.

The longer-term question about how a decline in ship tracks will impact global climate and temperatures, if at all, is something that will take far more study to determine.

“Ship tracks are great natural laboratories for studying the interaction between aerosols and low clouds, and how that impacts the amount of radiation Earth receives and reflects back to space,” Yuan said in a statement released by NASA. “That is a key uncertainty we face in terms of what drives climate right now.” •