Signet Maritime Corp. has begun construction on the first commercial vessels in the United States developed using a purely 3D design process.

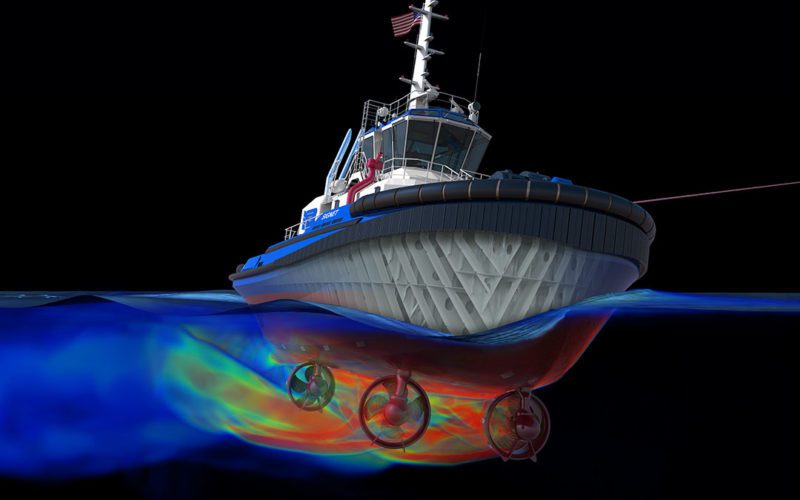

The tugboats will be built to the Advanced Rotortug design by Robert Allan Ltd., which places two azimuthing drives forward and one aft. The concept was first developed by Dutch company Kotug, and tugboats outfitted with this propulsion package are known for their maneuverability and escort prowess. Signet will operate the tugs at the Port of Corpus Christi in Texas.

The 3D process fundamentally changed how vessels move from concept to design to construction. According to ABS, this new model saves time and money during the design process and streamlines collaboration between designer and customer. Taken together, this model can reduce design time and speed up the start of construction, among other benefits.

“It has allowed us to have far more input into the final boat we build, and to better understand our decision-making in the early parts of the design,” Timothy McCallum, Signet’s vice president of engineering, vessel dynamics and economics, said of the 3D design.

Naval architecture has evolved from paper plans to computer-aided design (CAD) on its march to a 3D model. During earlier methods, modification could necessitate a new set of drawings. Improvements in computing power and software have paved the way for a fully digital design process.

Naval architects at Robert Allan Ltd. (RAL) have used 3D design for some time, starting first with hull forms and then hull surface development, according to James Hyslop, the firm’s director of project development. Those initial steps led to structural work, but each step remained separate and each process was typically handled by different software. Integrating these different elements made it possible for virtual walk-throughs and other forms of visualization to finalize the placement of various machinery and controls within the hull, he explained.

The process is now familiar and reliable. Naval architects can quickly review a set of plans and see how different aspects could be improved, Hyslop said. “It has become really useful.”

The ability to work in this manner, using this type of technology, has been a matter of considerable long-term work for the firm’s naval architects. Off-the-shelf software packages alone don’t feature the necessary level of integration.

Ultimately, Hyslop said, the process is moving toward a “parametric-type model,” meaning if you define the model well, you can start with a 80-by-40-foot tug design and scale it accurately to vessels of other sizes.

Hyslop said the overall process is not dramatically faster than traditional ways of generating plans, but is less prone to error. And it is particularly helpful with getting approvals from customers and in working with classification societies such as ABS. That’s especially true on newer designs.

“We have libraries of existing designs, but when we are working on something new, it helps everyone,” Hyslop said. And while many organizations continue to get excellent results from a 2D computer-aided design system, he is confident 3D will grow in importance across the maritime industry.

From an economic perspective, it doesn’t add any cost for the customer and it makes the process smoother.

Signet paints a similar picture of the evolution and the benefits of adopting a fully 3D design. McCallum said the design effort allowed for ongoing collaboration on the hull using a live and evolving model. That process gave Signet a consistent understanding of the relationships between structures. It also provided 3D measurements of components, clearances for welding and construction, and other key details that would traditionally have had to be derived from the 2D structural plans or a final assembly model.

Likewise, class and regulatory review has taken place with comments on the same model, working from the same detail, McCallum noted. Then, after approval, the hull components that make up the model are individually nested, cut and detailed out in assembly drawings for construction by the shipyard. Designer, owner, class society and builder all work from the same source, which reduces the risk of drawing inconsistency or rework from survey, McCallum said.

There’s always a risk in trying something new. In this case, there were concerns about software for the model review or potential delays in learning the program. “But the benefits of removing so much 2D interpretation from the design and construction process outweighed these concerns, and all involved mitigated the risks effectively,” McCallum said.

Construction began on the new Rotortugs last summer at the company’s shipyard in Pascagoula, Miss. “They will be built in our 43,000-square-foot covered fabrication area, and launched with our new 1,650-ton dry dock. We have built five state-of-the-art tugs like these there in the past 10 years,” McCallum explained.

Signet expects the 3D design product will lead to more efficiency at the yard, more consistent lifecycle surveys and more repeatable designs. Those benefits should extend past construction, allowing for more effective structural repairs down the road.

“It’s an exciting leap forward for the way Signet builds and manages its fleet,” McCallum said.

This novel change in vessel design also required buy-in from regulators. The U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center conducted an evaluation of the 3D model to determine the viewing software’s usability for plan review, according to Lt. Cmdr. Brittany Panetta. She said the Coast Guard embraces technological advancements like those made possible by 3D design.

With ABS as the third-party design verification agent, “this project affords a great opportunity for the Coast Guard to evaluate how efficiently and effectively we can verify compliance with federal standards when a vessel’s design is presented in 3D format only,” she said.

ABS expects the successful completion of the Signet project will lead to more using this cutting-edge 3D process.

“This landmark achievement sets the bar for future projects both in the U.S. and internationally,” said Christopher Wiernicki, ABS chairman, president and CEO.

“The advantages are significant,” he continued, “and we are confident that once the industry develops the infrastructure to handle 3D models in shipyards, a pure 3D process will become the default approach.”