A year after the Panama Canal opened its new locks to accommodate larger ships, tugboat captains say canal officials still have not addressed many safety concerns, including a lack of training and a shortage of tugs that can handle the challenges of the expanded waterway.

Capt. Donald Marcus, president of the International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots (MM&P), said the labor union outlined its concerns in a statement released in April of this year.

“They have to understand it’s a problem, they just have to address it and put some money in it and get some equipment and train new people,” Marcus said. “It’s like building a massive office tower without sufficient elevators to carry workers quickly to their offices.”

The Panama Canal Authority says the claims by the MM&P are false. “Regarding tugboats, the Panama Canal has more than adequate resources to attend the current operations of the canal and meet the industry demand,” said Monica Martinez, spokeswoman for the PCA. She also rebutted MM&P claims that fewer ships than anticipated are going through the new locks.

The Panama Canal as a whole is setting monthly tonnage records as a result of the expansion, according to the authority. In January, 1,260 ships transited the canal, carrying 36.1 million tons of cargo, according to an authority news release. The record before the new locks opened in June 2016 was 30.4 million tons in October 2014.

However, tugboat captains say there are still major problems in transiting the canal. They say that with the largest ships and two tugs in the new third lane of locks, there is very little room for the tugs to maneuver.

The new canal can handle neo-Panamax vessels up to 1,200 feet long, which is 235 feet longer than possible in the original locks; 160.7 feet wide, an increase of 55 feet; and with a draft of up to 49.9 feet, an increase of 10.4 feet. The new lock chambers are 1,400 feet long by 180 feet wide, according to the Panama Canal Authority website.

In the original locks, locomotives called “mules” help guide vessels through the canal. In the new locks, two 85-foot tugs at the bow and stern guide ships during their transit. “You’ve got a 1,400-foot lock and a 1,200-foot-long vessel,” Marcus said. “That just doesn’t leave much room for leeway.”

|

|

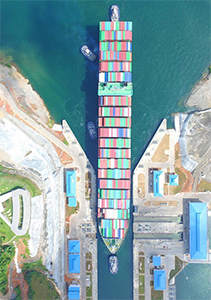

Four tugboats assist a neo-Panamax containership as it enters the new locks. The Panama Canal Authority and mariners’ unions disagree on how many tugs are needed to safely service the expanded canal. |

|

Courtesy Panama Canal Authority |

In addition, canal tug captains say neo-Panamax ships are limited in their ability to maneuver, with small rudders relative to their hull size and engines that are not designed to operate at the low speeds required while in the locks. “It’s a challenge that keeps the tugboat personnel continually on the job (and) contributes to fatigue and potential accidents,” Marcus said.

Tug captains also say that the training provided by the canal authority does not prepare them for the actual conditions in the new locks.

Capt. Ivan de la Guardia, secretary-general of the Panama Canal Captains Union, said the group specifically asked that some captains and crew be sent to Europe to train in canals that are similar to the new Panama Canal. “We wanted to have the opportunity to see what they had over there and how they did it,” said de la Guardia. He said the union provided a training program and protocols for the new canal that were rejected by the canal authority, as were requests for captains to go abroad for training. De la Guardia has worked on the canal for 20 years.

The canal authority maintains that captains have had plenty of opportunities to train. The authority created the Center for Simulation, Research and Maritime Development (SIDMAR) that offers a 210-degree training experience. It also built a scale-model training center, creating two lakes connected by a channel modeled after the canal’s Culebra Cut. This complex includes a docking bay and replicas of new and existing locks, gates and chambers at a 1:25 scale.

“The training facilities are deemed an excellent tool for training … in the opinion of the vast majority of the users, since (they) replicate the behavior of vessels in the expanded canal with a high degree of accuracy,” said Capt. Guillermo Manfredo, operations captain for the Panama Canal Authority.

The authority also chartered a neo-Panamax vessel for tugboat captains and pilots to train on as it made transits through the new locks. However, only 30 percent of tug captains were able to train on this ship, a bulk carrier, and the training came very late in the process, de la Guardia said. The union believed that the training was so important that it paid to send two captains for a week of training on locks in Europe: one to the Netherlands and one to Germany. “These guys came back with tons of videos, pictures, recommendations and procedures,” but the canal authority was not interested in this research, he said.

Captains also say the PCA has no procedures in place in case of an emergency, a matter of extreme concern. “What happens if we lose an engine or we lose steering (in the new locks)?” de la Guardia said. “What if we part a line?” As a graduate of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, he said he was taught that “for every procedure or maneuver you do, something can and will go wrong — and you prepare for it.”

Captains have resorted to sharing their experiences to come up with contingency plans, de la Guardia said. “If we follow this method, we are waiting for something to happen in order to fix it,” he said.

|

|

The new Panama Canal locks, designed to handle the next generation of megaships, opened in June 2016 and doubled the capacity of the waterway. The smaller locks that comprise the original canal can be seen in the background. |

|

Courtesy Panama Canal Authority |

Manfredo said the PCA’s Emergency Response and Canal Protection Division has developed contingency plans for emergencies. In the case of tugboat failure, “you have to remember that the vessel uses (its) own power and steering. This scenario is not considered a worst-case scenario, and the usual response is to secure the vessel to the chamber wall until the tug is either repaired or replaced,” he said. “This is not a hypothetical situation and on the occasions where we have experienced tug failure, the standard response described (has) proven satisfactory.”

Union officials say that the canal authority is not providing enough tugboats to assist vessels through the old and new locks. In its April news release, the MM&P said that only 33 of 46 tugboats owned by the PCA were operational. There should be 70 to 90 tugs that can handle the challenges of the new canal, the union said. Tugboats built in China and Spain for the expansion have had continual problems and are not always operational, according to the MM&P release, resulting in the PCA contracting with a Venezuelan company to provide additional tugs.

The PCA maintains that 46 tugs are sufficient to handle the traffic now transiting the Panama Canal. Of that total, 36 tugs are assigned to daily operations and 10 are on standby, according to Manfredo. Twenty-seven tugs can handle neo-Panamax vessels. The authority also has a contract with a local tug company to provide additional vessels when there is a spike in demand, Manfredo said. He said that union claims that the canal authority plans to privatize tug services are false.

De la Guardia also said that the PCA does not have enough personnel on hand, with captains averaging 60 to 100 hours on the job each week. “Management knows it’s more convenient to have guys work 16-hour days rather than hire more people,” he said.

Manfredo said the PCA is re-evaluating the requirements of the tugs as well as the manning in order to adjust resources if necessary. “At the Panama Canal, the tugboat crew is relieved three times in a 24-hour period, which is not the case … around the world,” he said.

Union officials are frustrated that their concerns have not been addressed given that the expense is not significant compared to the overall $5.2 billion cost of the expanded canal.

“I think it is penny wise and dollar foolish, considering the size of the operations, to not have enough resources for manning, for sufficient tugs, and to make sure the training has been covered,” said Marshall Ainley, president of the Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association. “It is kind of mind-boggling.”