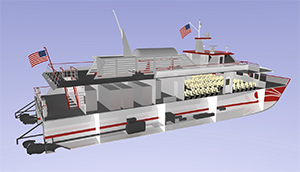

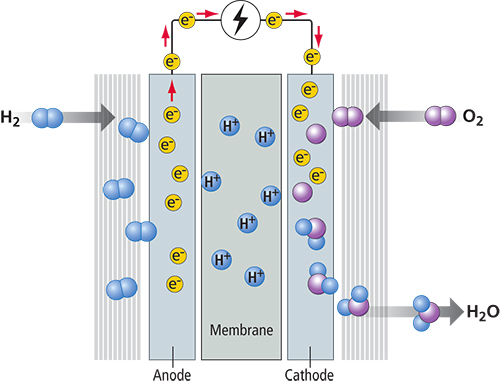

The recent news out of the Golden State was surely eye-catching: a glimpse of a trim, twin-hull ferry called Water-Go-Round from Golden Gate Zero Emission Marine, being built with a cool $3 million grant from the California Air Resources Board (CARB). The vessel’s name hints at its uniqueness. It will be the first commercially operated ferry in the world to be powered by fuel cells — combining hydrogen and oxygen to make electricity — with water as a byproduct.

Designed by Incat Crowther and under construction at Bay Ship & Yacht Co. of Alameda, Calif., the 70-foot aluminum catamaran will have a top speed of 22 knots and is scheduled to launch in mid-2019. But is this just an experiment, or is it a glimpse of the future?

Melanie Turner, public information officer at CARB, said Water-Go-Round is one of the board’s off-road advanced technology demonstration projects that are designed to help accelerate the next generation of vehicles, equipment and emissions controls that are not yet commercialized.

“Commercial marine vessels, from oceangoing vessels to commercial harbor craft, are a significant source of air pollution emissions — diesel particulate matter and smog-forming oxides of nitrogen and sulfur oxide — contributing to California’s air quality and climate challenges,” she said.

|

|

A study for the San Francisco Bay Renewable Energy Electric Vessel with Zero Emissions (SF-BREEZE) found that it was technically feasible to build a high-speed, hydrogen-powered ferry in California with full regulatory acceptance. The study was led by Dr. Joe Pratt, co-founder of Golden Gate Zero Emission Marine, when he was at Sandia National Laboratories. |

|

Courtesy Elliott Bay Design Group |

The state, with the cooperation of affected industries, is working to develop policies and programs to address environmental impacts resulting from growth in the movement of goods in California. In an effort to reduce diesel emissions from port-related sources, CARB has regulations for cargo-handling equipment, commercial harbor craft, port trucks, and ship auxiliary engines and main engines, Turner said. There are even vessel speed reductions in the mix.

In response to state Assembly Bill 617 in 2017, CARB established the Community Air Protection Program, which focuses on reducing emissions in communities most impacted by air pollution. Most major sources of diesel emissions —ships, trains and trucks — operate in and around ports and rail yards, and on heavily traveled roadways. This infrastructure, in turn, is often located near highly populated areas. Because of this, large numbers of people in urban areas, particularly near ports, are exposed to disproportionately higher concentrations of diesel particulate matter.

While California may be generating headlines with this particular vessel and the state’s rush to alternative fuels, it’s not the first entity to plug hydrogen. In 2000, a large fuel-cell-powered launch, Hydra, was tested on the Rhine River near Bonn, Germany. Several other fuel-cell vessels have debuted since then, including the first German Type 212 submarine and Hydrogenesis, a tour boat in Bristol, England, in 2013.

Although never turned into a working prototype, a fuel-cell vessel has been considered before for the San Francisco Bay Area. The possibility of a hydrogen-powered ferry was the subject of a study, conducted by Sandia National Laboratories and released in 2016, that focused on a high-speed, 150-passenger design. After examining economic, environmental and safety factors, the study’s authors concluded that construction of such a vessel — their concept was called SF-BREEZE — was indeed practical.

Challenges vs. potential

Ryan Storz, an assistant professor in the Engineering Technology Department at California Maritime Academy, sees a bright future for hydrogen fuel cells but acknowledges challenges, too. He said Japan is pushing hard to move to hydrogen “in a post-Fukushima world” and is looking to build a shipping terminal to import it from the United States. Furthermore, he said other Asia-Pacific nations are looking to produce hydrogen “on a renewable basis.”

“The primary attraction it is that it is an energy source that can be stored on location or it could be used for mobile fuel, both for combustion and fuel cells,” Storz said. He added that the city of Oakland is currently operating 10 hydrogen-powered buses and 10 natural gas buses to compare their performance and economics.

“I believe right now the refueling station is the piece that everyone is trying to understand because compression is difficult. But if you move to cryogenics where you’re pumping it as a liquid, it is more reliable,” Storz said.

|

|

Hydrogen fuel cells, like the ABB system shown here, generate energy by exploiting an electrochemical reaction at the interface between the anode or cathode and the electrolyte membrane. They involve no combustion, converting fuel directly to electricity and heat with water as a byproduct. |

|

Pat Rossi illustration |

However, that’s only practical when the operator is in an area with substantial hydrogen use because, just like liquefied natural gas (LNG), hydrogen has to “boil off” periodically. This boil-off rate is relatively fixed and is less economically acceptable when the fuel is in storage longer. On the other hand, if there is relatively rapid turnover in supply, the boil-off loss ends up representing a smaller percentage of overall fuel use.

Of course, Storz said, it can be a win-win situation: LNG tankers often run their engines on boil off. In some sense, LNG is paving the way safety-wise for the hydrogen industry, getting people used to working with liquid fuels, he said.

Storz wasn’t certain about the comparative economics of hydrogen, but insisted the technology is competitive. The main issues are refueling logistics, safety and regulatory requirements.

Certainly, the infrastructure has a long way to go. According to Storz, there are currently only two tanker cars in the United States that can transport cryogenic hydrogen by railroad, and then only in limited areas. But hydrogen advocates always tout the comparative ease of turning alternative sources of energy, which California is expanding, into sources for hydrogen. Siemens electrolysis technology, already deployed commercially in Europe, can take input water and “surplus” electricity and use it to separate hydrogen. It can then be used as either a combustion fuel or in fuel cells like those creating electricity for Water-Go-Round.

What’s more, the country has a lot of hydrogen experience thanks to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Cryogenic hydrogen has been around since the Kennedy administration and the moon program, and NASA shipped huge quantities of it down the Mississippi River. Storz suggested it might make sense for the maritime industry to tap into the expertise from the U.S. Coast Guard in that region to help convey lessons learned and develop modern best practices.

An eye toward training

Storz said that while experience with LNG has been a good learning process, more needs to be done in terms of training to prepare the maritime industry for hydrogen. “The only hydrogen training I am aware of is at the U.S. Department of Energy, which has some first responder training — and I think that may be just online training,” he said.

|

|

Water-Go-Round “will demonstrate that hydrogen fuel-cell powertrains are perfectly suited for a broad range of maritime applications while offering a compelling business case for adoption,” according to the project team at Golden Gate Zero Emission Marine. The vessel’s performance will be independently evaluated by Sandia National Laboratories. |

|

Courtesy Golden Gate Zero Emission Marine |

Storz pointed out that all mariners must have firefighter training as required by Coast Guard licensure, and that training is typically conducted at a physical location. “We should duplicate that for hydrogen,” he said.

His colleagues at the University of California-Irvine have already taken steps to develop fuel-cell training there, and Storz said he is anxious to get a safety and training program going at Cal Maritime’s Maritime Safety and Security Center in Richmond. On a related note, “Last year we hosted the first hydrogen import seminar in northern California,” he said.

Looking ahead, Storz said he believes hydrogen is a viable alternative fuel for maritime use.

“The nice part about hydrogen is it is mobile; you can build a plant in the middle of nowhere and ship it by barge,” he said. And, he added, there are some very mature companies around the world that have the technology to help make it a reality.