During a more than three-year slump in oil prices, two design firms teamed up to look at converting offshore supply vessels to dredges. Operators are seeking ways to repurpose OSVs to generate revenue, according to Virginia-based ship designers and engineers Gibbs & Cox and European designers OSD-IMT.

Low usage has left many modern U.S.-flagged OSVs stacked. Meanwhile, the nation’s dredging market is busy, particularly along the Gulf of Mexico, and it needs more equipment.

A study of these conversions, begun in mid-2017, was led by Geoff Dean, OSD-IMT’s United Kingdom-based business development manager and naval architect, and Mark Masor, a naval architect and Gulf Coast operations manager at Gibbs & Cox. Together they considered converting supply vessels to trailing suction hopper dredges from a shipyard perspective, with technical factors in mind. The team reviewed U.S. Coast Guard requirements and other regulations and researched the economics of conversions. After writing up their findings, the architects presented them at the International WorkBoat Show in New Orleans on Nov. 30.

According to Dean, the long, parallel mid-bodies and open working decks of OSVs make them suitable for conversions. OSVs share common configurations with other vessels and already have been repurposed to carry containers, lay cables and support wind farms. U.S.-flagged OSVs are classed by the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS), and most of them are certified or compliant with the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), Masor said.

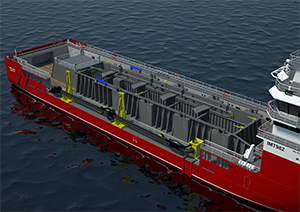

In their study, the designers used a typical 256-foot Gulf of Mexico supply vessel with mud tanks just below the main deck. They employed a basic IMT 978 design for a North Sea configuration. These vessels were converted to hopper-type, self-propelled dredges capable of removing material, storing it on board and dumping it in a disposal area.

The Gulf OSV’s liquid mud tanks were reconfigured to hopper tanks for the dredged material. An additional hopper tank was introduced on the main deck, and bottom doors were fitted to allow the discharge of material. Existing dry bulk tanks were removed to make space for dredge systems and to reduce weight. Removal of a section of the cargo rail allowed for the drag arm and davits to be deck-mounted.

A single drag-arm dredge system was used in the vessel for dredging to depths up to 55 feet with an electrically driven inboard pump. In future conversions, if electrical power isn’t available, the dredge pump can be driven by a diesel engine.

To dredge, a drag arm is lowered from the vessel to the channel’s bottom. As the dredge travels forward, the drag arm sucks water and sand mix from the bottom. This slurry passes through the drag head and pipelines into the hopper.

A cargo pump-out system was incorporated in the vessel so that dredge material can be sent to a barge or to shore for wetlands restoration or levee work. A supporting system with two high-pressure jetting pumps was employed.

Dredges keep waterways navigable and help protect and rebuild shrinking coastlines. Deep channels and berths are needed in ports, rivers, lakes and near-shore ocean waters for commercial and military vessels. For coastal protection, Louisiana in particular depends on dredging. Citing data from 2013, the architect team said that the Gulf of Mexico accounts for 67 percent of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ dredging and the Atlantic area for 20.8 percent.

Masor cited the advantages of the converted Gulf OSV, saying it would take a year to deliver versus a minimum of three years for a new hopper dredge to be built in the United States. The capital cost of converting an OSV to a dredge would be $6,000 per cubic yard compared with $12,700 per cubic yard for a newly built dredge. The repurposed vessel’s payback period on investment would be shorter at six years against 7.5 years for a new dredge.

A drawback to conversion is a lower dredge-material capacity versus a dedicated newbuild. And the architects said the converted vessel’s greater draft could limit the areas where it operates, compared with the working range of purpose-built dredges. In addition, fuel costs could be slightly higher for converted vessels than with purpose-built dredges of similar deadweight, based on differences in operating parameters. But a converted, modern OSV would still be more fuel efficient and affordable to operate than an older, extended-life hopper dredge.